Photo: ed_whetstone

At my desk is a sheet of various web photo passwords pinned to my cubicle, next to prints from the Columbian Exposition and the Union Stockyards. It's the sort of office flotsam that's a handy reference but interferes with my feng shui, but the photo editor who distributed it was kind enough to illustrate it with a photo to distinguish it: Marina City, from the same angle as Wilco's Yankee Hotel Foxtrot album cover (just before album covers became obsolete).

Today's the 100th anniversary of Bertrand Goldberg's birth, and a case can be made, I think, that he's the city's most beloved architect. Mies may be its most legendary, but his buildings aren't as distinct to the typical observer (in part because they're so easily imitated), Frank Lloyd Wright its most famous (though his footprint in the city proper is small). Goldberg built one of the city's most recognizable buildings in Marina City, one of the rare buildings to integrate parking in a way that's not hideous, something local architects essentially failed to do in the decades that followed; the Hilliard Homes (above) are an unusual example of period public housing to escape the wrecking ball by virtue of their beauty; Prentice Hospital, well, it put up a good fight. (It's not as beloved as the other Goldbergs downtown, but it has its structural charms.)

Goldberg's architecture was on the forefront of the city's re-embrace of its river: a fetid industrial corridor being slowly reimagined as a new-urbanist public space, essentially beginning with Marina City and River City.

Unfortunately, Goldberg's smaller works are physically lost to history as Prentice will be soon, but they're no less interesting and experimental. His first house, one of his first works as an architect, was a commission from Harriet Higginson, an "early feminist spirit" from a banking family in Boston and LaSalle Street stockbroker. And from the beginning, Goldberg came up with a clever use of materials:

a canvas-covered house was meant to provide a simpler house than we were currently constructing at that time, with the use of shingles or wood siding and things of that sort. It was also meant to provide a house that was more airtight than the houses that were being built at that time and certainly was a less expensive house.

In his fascinating, often entertaining oral history (SAIC's collection of architect oral histories is one of the city's great resources), Goldberg said that she wanted "a simple house that she could clean with a garden hose, inside and out, and I designed that house for her." It was a simple wood frame with a canvas exterior and a plywood interior, but the result, for a house built in the suburb of Wood Dale (just west of O'Hare) in 1934-35—Goldberg would have been a mere 21 or 22, with barely a year in the city—was quite mod-looking.

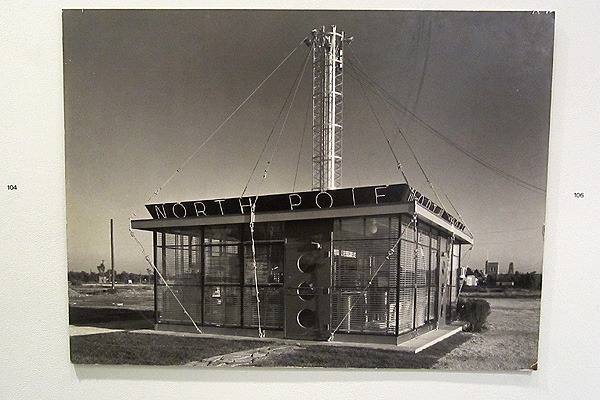

Shortly after establishing his own office, then just in his mid 20s, Goldberg applied the idea of Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion House—think an Airstream trailer crossed with a circus tent—which he would have noticed as a 19-year-old, to design one of his first commissions, and one of my favorite of his buildings, the North Pole Ice Cream Store—a portable, "mast-hung" store on a truck chassis. "It was tremendously interesting," Goldberg said, "and also I got quite fat while I was doing it because I wanted to find out how you made good ice cream, so I sampled ice cream all over Chicago."

Photo: chicagogeek/CC by 2.0

The pending disappearance of Prentice makes for something of an unhappy birthday for the late architect. But Prentice will be with us in our memories, including the memories of Chicago White Sox right fielder Alex Rios. (Did he become a Goldberg fan passing the Hilliard Homes en route to the Cell? That's kind of what did it for me.)

It's a bit late for Rios's star power to save Prentice, but if anything ever threatens the Hilliard Homes, preservationists know who to call.