Photo: ryaninc/CC by 2.0

Noam Scheiber's cover story in the New Republic is well worth a read (especially if you're wondering how the rich stay rich in Chicago). In the contemporary style of magazine headline writing—dramatic supposition not really supported by the article—it's entitled "The Last Days of Big Law." Which, you know, no (perhaps on a geologic timeframe).

But the article itself is a good look into the culture of elite law firms, mostly set in Chicago, and how they're a microcosom of the American economy: a brief-ish history of big law as a workplace and economic engine. And one that's all too familiar to me, as the husband of a lawyer who briefly toiled at a large law firm.

No, really, toiled:

As demeaning as life can be for a partner these days, it’s altogether soul-crushing for an associate. One of Mayer Brown’s young attorneys recalled scaling back her hours around the time her first child was born. The new schedule meant getting to the office by 6:30 a.m. so she could leave by 6 p.m., in time to put her daughter to bed. The problem arose when she had to work late, a not infrequent occurrence. “Then you’re in the office from 6:30 a.m. till 1 a.m. It sucks even more,” she says.

Periodically, some of the women partners would lead seminars on striking a work-life balance, but she found them of limited use. “The primary talk we would get was: ‘Outsource your life. Your husband can stay at home. Or you can hire a cook, a cleaning staff, and you can [spend time with your kids] on vacations.’ Thanks.”

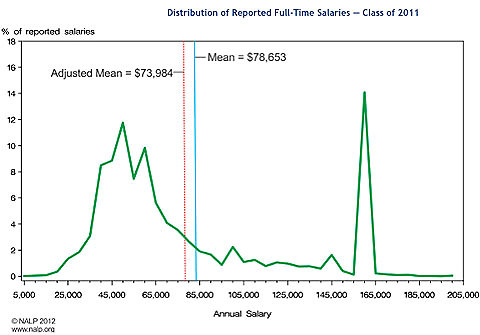

Granted, associates are very, very well compensated for their work. $160,000 is a good ballpark salary for Big Law. As Catherine Rampell describes the "bizarre market that is legal hiring," it's bimodal, really starkly so. Here's a chart showing the average starting salary for lawyers—associates at the big firms make up that spike to the right:

So $160k is not just a reasonable ballpark, it's an unexpectedly specific figure. And as Rampell demonstrates, the mean has been moving left because fewer big-firm associates are getting hired since the recession started.

When my wife and her friends began working at big firms, the impression I got was that it was a strange and possibly unsustainable industry, which turned out to be somewhat correct. What I didn't realize was how new this form of the industry was.

* In 1991, the median for new lawyers was $40,000. About 40 percent of lawyers made $30k-$40k, with six percent making $70,000, "the median in big law firms at the time."

* In 1996, 45 percent of lawyers made $30k-$40k, and the big-firm six percent made about $70k-$80k.

* And in the mid-2000s, things went nuts: "in the three years that followed — 2007, 2008, and 2009 — the right-hand peak shifted to $160,000, accounting for 16%, 23%, and 25%, respectively, of reported salaries. Meanwhile, the $40,000 – $65,000 peak shrank, accounting for 44%, 42%, and 32%, respectively of reported salaries."

At the rate of inflation, big-firm salaries would have increased by about 25 percent from 1996-2009. Instead, they doubled. While the salaries were doubling, big firms went on a hiring binge as well.

Meanwhile, the culture was changing. In 2010, Robert Helman, the former managing partner of Mayer Brown—who, in Scheiber's story, gets the credit for rescuing the firm after Continental Illinois Bank went belly-up and wiped out a third of the firm's revenue—wrote an essay describing the evolution of his business from the time he began at Isham, Lincoln & Beale in 1956 (not that Lincoln, but his son Robert Todd Lincoln) at a salary of $4,800, "the top 'going rate' at the leading Chicago law firms." $4,800 is the equivalent of $38,500 in 2010 dollars.

The firms have become much more businesslike. Compensation has increased dramatically. Starting salaries are now $160,000, not because of overall price inflation or because the newly graduated are more able than we were, but because the firms are enslaved in a market trap of their own making.

In return for very high compensation, the younger lawyers are expected to work very long hours, not just when clients have emergencies, but to generate revenue – a Faustian bargain that leaves time for little else. Family and personal lives often suffer, as does the opportunity to contribute to the community and the profession. The pyramid to be climbed has increasingly steep sides, and most associates understand they will not become partners.

Emphasis mine. He's not kidding about overall price inflation. After more than a decade in the business, Helman joined Mayer Brown in 1967 as an income partner at $33,000 a year, or $215,000 in 2010 dollars, not a great deal more than associates would make after he retired from the firm in 1998 and salaries went to the moon. (And from 1971 to 2011, law school tuition "increased by a factor of four in real [inflation-adjusted] terms," as the size of the industry, as a percentage of the economy, actually shrank.) Partners, as Scheiber documents at length, were then making bonuses almost twice the size of Helman's starting salary as an income partner. Firms followed the economy up the mountain, and then off the cliff.

It's not just an economic issue, though; it's also a cultural one. A year before Helman looked back on his career, Mary Hutchings Reed, a former partner now of counsel at the similarly elite Winston & Strawn, also looked back on a career that started 20 years after Helman's, and came to similar conclusions:

Harder still for a lawyer billing by the hour to suggest that she do only the most important things, or the most cost-effective things. So now we're more efficient, but we do more and bill more, and balance less. We've become adept at the metrics for measuring our productivity, but we frequently mistake our billings for our value and self-worth. We don't know how to quantify professional values, such as thoughtful analysis, creativity, learnedness, and commitment. Are we, as a profession, "better" lawyers now than then? I don't know. I do sense that we spend too much time lawyering, at the expense of our personal lives.

Large-firm practice is today technologically more efficient, facially more diverse, institutionally more conscious of women and minorities, formally supportive of pro bono, and structurally more suited to alternative work arrangements. However, largely because of technology, today's firms are also more time-consuming, more demanding, more money-conscious, less intellectual, and less human.

It's an evolution paralleled by that of investment banking, which Mary Ho found in her excellent book Liquidated.

What was once a stable entry into the respectable upper-middle-class—"a profession, not a lifestyle," as Reed describes it—evolved very quickly into a hypercompetitive world of brutal hours that made people very wealthy, but destabilized employees and eventually the firms that employed them. What's left looks a lot like the economy as a whole: layoffs, contract workers, and an industry in search of the stability it once had.