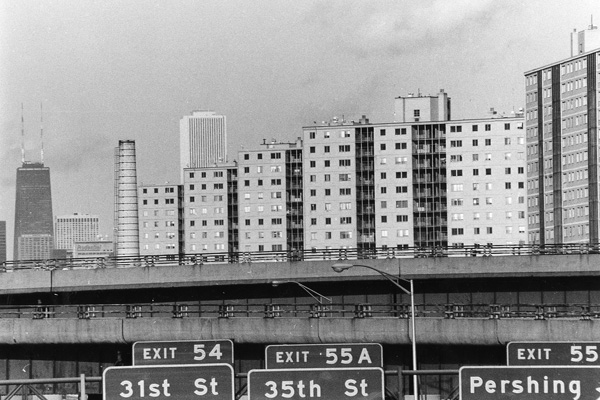

Photo: Frank Hanes/Chicago Tribune

The Robert Taylor Homes and the Dan Ryan Expressway, 1984.

After Detroit filed for bankruptcy, the first writers I wanted to read were the natives—writers with not just broader expertise in politics and economics but with a connection to the city's history, for a combination of not just what the numbers say but the stories people there tell each other about what happened.

One of those writers is New York's veteran political writer Jonathan Chait, who hit on one of the themes I kept seeing over and over in "How Detroit Really Is Like America":

The 1967 riots were an event so traumatic they still hovered over the city when I grew up there in the eighties. The city burned down, and kept burning for years and years. The owners of its huge stock of abandoned, worthless properties would set arson fires, usually using the cover of “Devil’s Night,” a night-before-Halloween folk holiday of pranks and vandalism that as a kid I thought was observed everywhere but turns out to be mainly a Detroit thing. The city would have hundreds of fires of Devil’s Night, up to 800 a year at its peak.

Carl S. Taylor, a Detroit native and Michigan State sociologist, told Scott Martelle for the latter's Detroit: A Biography:

"The riot changed everything." … Taylor grew up in the area near where the riots started, and believes those few days of violence marked Detroit's transition from a place of relatively mixed stability, with intact social institutions and viable neighborhoods, to what he refers to as the "third city." Detroit's mores turned upside down, and Detroiters began embracing what had been marginalized—the illicit economy of stolen goods, extralegal activities, the glorification of the violence, and the framing of the police and other governmental institutions as enemies.

And Edward McClelland, from Lansing Flint, in his recent book Nothin' But Blue Skies:

But the riot itself is less interesting than its aftermath. It was the B.C./A.D. week in Detroit's three-century history. After it was over, Mayor Cavanagh visited Twelfth Street, declaring sorrowfully, "We stand here amid the ashes of our hopes." In the 1960s, black ghettoes burned in other big cities—Los Angeles; Chicago; Philadelphia; Washington, D.C.—but none of the riots had the consequences of Detroit's. Beforehand, Detroit had been losing about twenty-thousand white residents to the suburbs each year, a normal rate of defection for a Northern city. The year after the riot, eighty thousand whites left Detroit, for suburbs with well-established policies of keeping out the colored.

All this is reminiscent of Gary Rivlin's old Chicago Reader piece, "The Night Chicago Burned," about the West Side riots of April 1968. As McClelland suggests, it didn't have the effect of Detroit's (much deadlier) riots on the whole of the city, but it did permanently damage whole swaths of it while changing the commercial and racial makeup of the city:

Whites had begun fleeing to the suburbs long before 1968, but never at the pace exhibited for the next several years. Marie Bousfield has worked for Chicago's Planning Department, plotting and charting change in the city's population, for 15 years. "It's my view that the riots were the cause of what you call 'white flight,'" Bousfield told me recently, though she was quick to add that that's only her personal feeling. Numbers are the lifeblood of her work, and she knows of no conclusive data to back up her instinct, but she is certainly not alone in believing that the riots were at least partly responsible. There's no doubt that there was a dramatic increase in white flight—"out-migration," in Bousfield's argot—during the early 70s; nearly half a million people left the city between 1970 and 1975. (Bousfield has no hard data on the year 1969.) And there can be no doubt that some people saw the West Side riots as some sort of early warning of things to come, and acted upon those fears.

Businesses also left in droves. The commercial life of the West Side was literally gutted; to this day, residents complain that it is impossible for them to shop in their own neighborhoods. And factories left, taking their valuable jobs to the suburbs. At the time of the riots, for instance, there was a thriving machine-tool industry centered along Lake Street, west of the Loop.

There are still some remnants of the machine-tool industry today along Lake, but very little in the way of other commerce. 50 years later, the gentrification of Fulton Market is slowly pushing west towards Ashland.

The Detroit riot of 1967 is also known as the 12th Street Riot, for the area where the riot began. And the population that lived there had, in part, been recently displaced by urban renewal from Paradise Valley, undeniably a slum, but a culturally and economically critical one to the city's black community (John Lee Hooker's breakthrough song "Boogie Chillen'" is about the neighborhood). It fell to the wrecking ball, replaced with the Chrysler Expressway.

Thomas Sugrue, in his classic The Origins of the Urban Crisis, writes:

Left behind was what one black businessman called a "no man's land" of deterioration and abandonment. The announcement of highway projects came years before actual construction. Homeowners and shopkeepers were trapped, unable to sell property that would soon be condemned, unable to move without the money from a property sale.

I thought about this while running some numbers about crime in Chicago. I've done enough of this that I can predict pretty well where certain neighborhoods will end up, so I was unsurprised to find particular problems in Fuller Park, the city's smallest community area, just south of U.S. Cellular Field. It often ends up at or near the bottom of many measures of health and well-being in the city, and has for decades. (Before it became part of the city, it was populated by immigrants living in cheap housing that had been built on its outskirts to avoid the strict post-Great Fire building codes.)

In the mid 1950s, its tuberculosis rates were twice the city's average; in 1954, the Tribune singled it out in an article entitled "Worst Slums Turn Sorriest Face to Visitor," about how unfortunate it was that passengers on the New York Cental and the Rock Island were routed through it. 47th Street, the center of Fuller Park, was judged the city's ugliest of all its tenements.

Today it's squeezed between the Dan Ryan on the east and railyards on the west, just a few blocks wide at its widest point; for over a decade, from the late 1960s to the early 1980s, metal gates closed its north end from Canaryville and Bridgeport, almost completely sealed off from the rest of the city. In the late 1990s, 46 percent of children in the neighborhood had elevated blood lead levels; the death rate for African-American men was 340 percent higher than the national average—when the citywide average was 51 percent higher.

There are small green shoots, like the 16-year-old Eden Place Nature Center, the inspiration for which was Fuller Park's lead-poisoning levels. But its population continues to shrink.

Despite the recent handwringing, Chicago is not Detroit, as Edward McClelland explained in a recent issue of Chicago. It doesn't have an industrial monoculture; its central city is expanding quickly; for the industries it has lost, it still remains where the industry of the Midwest flows through, both its physical goods and its money. Detroit was much more vulnerable to riots, to urban renewal, to the destruction of its neighborhoods. Some cities are more immune to self-inflicted wounds than others, but in cities that aren't Detroit, you can still see the scars.