Yesterday the secretary of the Department of Housing and Development, Julian Castro, announced potentially groundbreaking changes in how the federal government will deal with fair housing laws. Pointedly, he announced those changes in Chicago, which has been shaped so much by public-housing laws and done so much to shape them across the country.

The basics are this. For years, HUD required that localities do an "analysis of impediments" to fair housing. If that sounds abstract, that's because it was. As a panel chaired by two former HUD directors put it:

HUD does not require that [analyses of impediments] be reviewed or approved . . . as a condition of funding and there are no HUD regulations that identify what must be included in an AI, not even a requirement that efforts must be made to reduce existing segregation, consider residential living patterns in the placement of new housing, or promote fair housing choice or inclusivity.

And this lack of guidance was paired with a lack of oversight As HUD itself puts it:

Prior to this rule, HUD directed participants in certain HUD programs to affirmatively further fair housing by undertaking an analysis of impediments (AI) that was generally not submitted to or reviewed by HUD. This approach required program participants, based on general guidance from HUD, to identify impediments to fair housing choice within their jurisdiction, plan, and take appropriate actions to overcome the effects of any impediments, and maintain

records of such efforts.

The new rule requires an "assessment of fair housing," a seemingly mild wording change from "impediments," but one that's meant to signal a much more broad robust approach that takes into account many criteria—racial segregation, access to transit and jobs, school quality, environmental justice—and provides open data with which to measure the criteria.

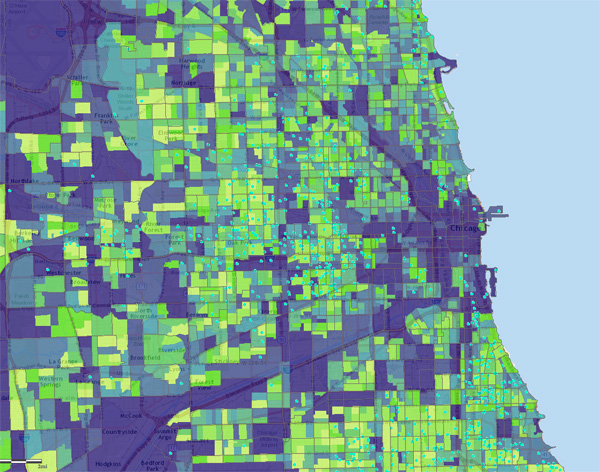

For that, HUD built a mapping tool. Say you wanted to look at housing voucher recipients versus job access in the Chicago area. Voila (green is low access, purple is high):

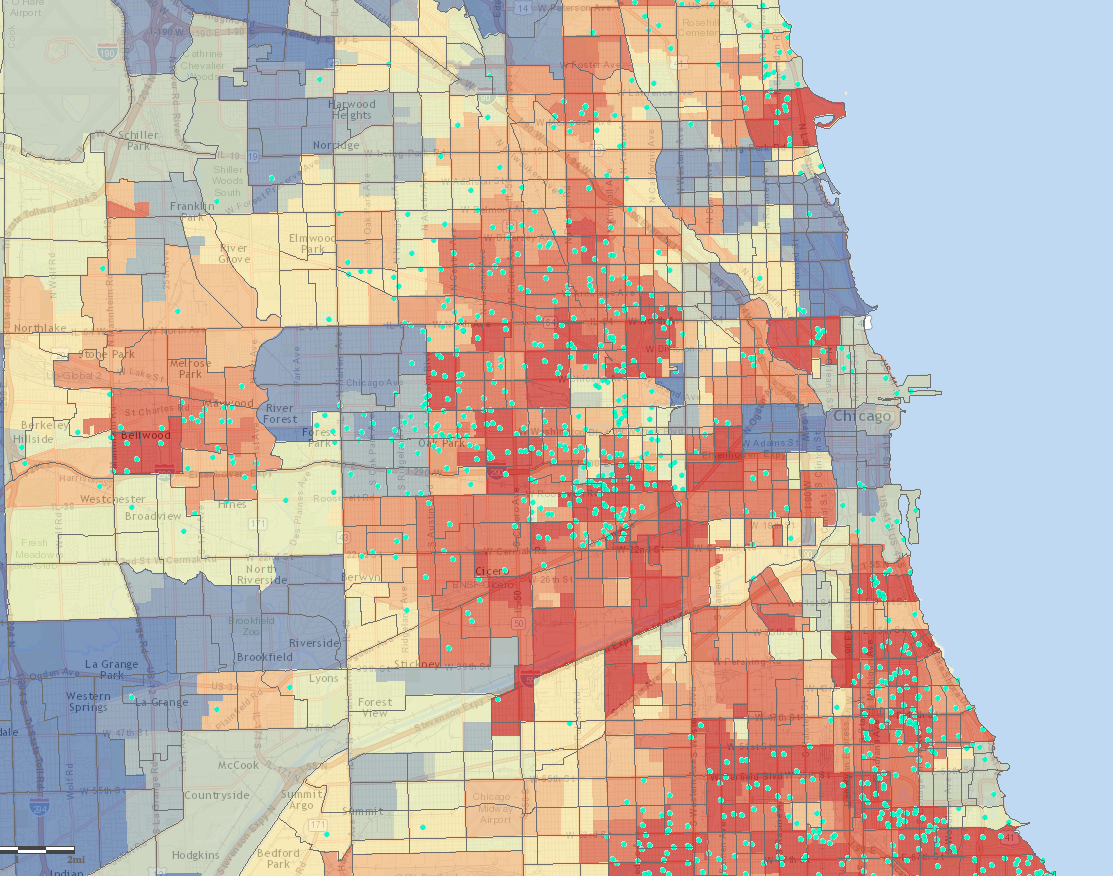

Not great. Or, more strikingly, school proficiency (red is low, blue is high):

There's nothing magic about the data; it's pretty basic and widely available. HUD will offer it to jurisdictions as a tool, but it's the kind of data that most jurisdictions and advocates have on hand. But it does reflect and emphasize HUD's priorities, and what jurisdictions will need to focus on to deal with the new rule.

What can be done is visible in the map above. Locally, one of the outliers of voucher recipients living in an area with high school proficiency is Oak Park. And there's a reason for that, as David Moberg wrote in 2011:

In a contentious 1968 campaign, the activists pressed the City Council to pass a municipal fair-housing law. Then they promoted policies to make the community stable and appealing to outsiders by banning realtor solicitation and for-sale signs, strictly enforcing building codes and widely advertising Oak Park as desirable and diverse. The nonprofit Oak Park Residence Corporation, created in 1966 to deal with rental disinvestment, bought, rehabilitated, and rented out potentially problematic apartment buildings. The city offered insurance protecting equity in homes to discourage panicky sales.

For almost 50 years, Oak Park has not only welcomed subsidized housing, it's also worked to desegregate housing patterns within the neighborhood, rather than settling for overall diversity that is segregated at street level. Prophetically, Moberg continues:

The federal government could play a significant role in helping more communities succeed as Oak Park has. Rob Breymaier says that even though President Barack Obama has been reluctant to speak out on racial issues, Obama has quietly appointed top administrators to the Department of Housing and Urban Development who are interested in residential diversity.

So that happened. And just a couple weeks ago, the Supreme Court said that the Fair Housing Act prohibits unintentional discrimination, not just the much higher bar of intentional discrimination.

HUD's new rule has similar implications. Rather than mere "impediments" to fair housing, it lays out four goals: reducing segregation, eliminating racial and ethnic concentrations of poverty; reducing disparities in access to jobs, transit, and quality schools; and targeting groups with "more severe housing problems," like the disabled or families.

Then, jurisdictions seeking grants would have to explicitly address those goals, using the data provided by HUD and facing a review by HUD of their assessments for fair housing. It works both ways—governments have to think about these things, and HUD can't blow it off either.

What will HUD do then? That's another question. Emily Badger writes: "Officials insist that they want to work with and not punish communities where segregation exists. But the new reports will make it harder to conceal when communities consistently flout the law. And in the most flagrant cases, HUD holds out the possibility of withholding a portion of the billions of dollars of federal funding it hands out each year."

So that rather important part remains abstract. It's likely that fair-housing advocates, like the Inclusive Communities Project that just won its case in the Supreme Court over the issues HUD's rules seek to address, will continue to bear much of the burden. But the new rule raises the standards for both HUD and the jurisdiction it works with, and gives advocates the tools to hold them to it.