The S.S. Eastland tipped over in the Chicago River only three years after the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic. With a death toll of 844 passengers, the disaster took half as many lives as that famous shipwreck, but it hasn't received nearly half the attention.

According to Eastland: Chicago's Deadliest Day, a new documentary airing July 25 at 8 p.m. on WTTW, the Eastland disaster can teach us a lot about ethnicity and class in Gilded Age America. Both help explain why it happened, why the boat's owners were never held accountable, and why it's been forgotten.

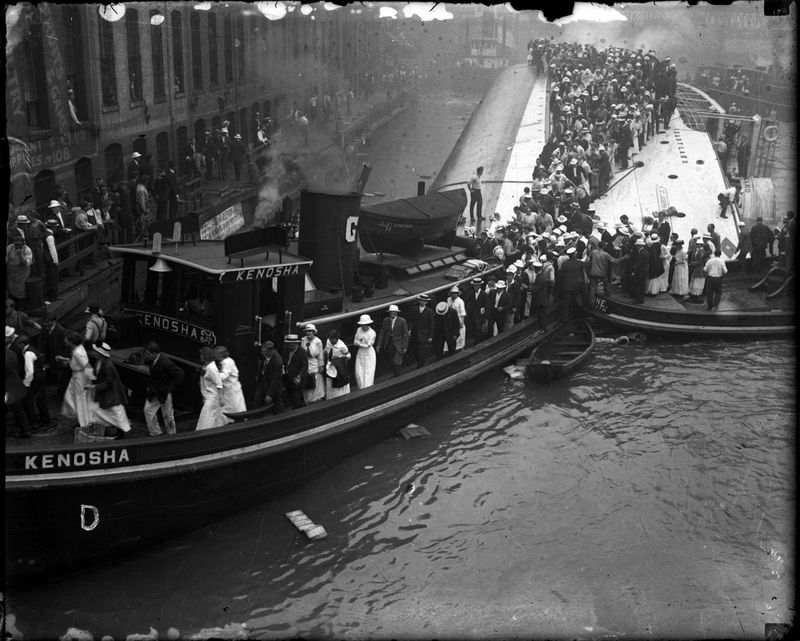

On July 24, 1915, more than 2,500 employees of the Western Electric Company in Cicero — many of them Czech immigrants — piled onto the Eastland for a picnic excursion to Michigan City. The overloaded boat listed to port, then finally tilted over entirely.

It was the worst maritime disaster in the history of the Great Lakes, but today, it is only memorialized by a historical marker at the corner of LaSalle and Wacker. In the words of Jay Bonansinga, author of The Sinking of the Eastland: America's Forgotten Tragedy, the ill-fated boat was "a blue-collar Titanic."

"This was not John Jacob Astor and other rich folks traveling across the Atlantic," says Chuck Coppola, one of the documentary's producers. "This is a steamship on the Great Lakes carrying factory workers. The optics of the Titanic are different. It was an ocean liner filled with wealthy people. The Eastland sidles over into a muddy river. It's just less dramatic."

The Eastland's fatal flaw was that it had been designed like a cargo ship, which carries its weight in lower holds, not like a passenger ship. Its ballast system was not nimble enough to balance a top-heavy load.

In spite of that, the ship's owner, the St. Joseph-Chicago Steamship Company, never paid a price for the loss of life. The company's officers fled to Michigan to avoid a federal charge of operating an unsafe ship. They avoided extradition to Illinois with the help of defense attorney Clarence Darrow and were acquitted by a judge in Grand Rapids. Had they been extradited to Chicago, says Coppola, it would have been "a much more hostile trial" in front of a much more hostile judge: jurist Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who would later become the first Commissioner of Baseball.

"These were wealthy shipowners who had almost no experience owning a steamship," Coppola says. "To me, the damning point is that they knew this was not a perfect steamship, but they thought putting 2500 passengers on board was an acceptable risk."

This is the second Eastland documentary Coppola and coproducer Harvey Moshman have created for WTTW. The first, in 2001, was put together in three months. This time, they spent three years on the project, which was funded by the Chicago Marine Heritage Society.

The time and the money enabled them to produce a dramatic re-enactment of the disaster, filmed aboard the S.S. Keewatin, an early 20th-century steamship of the same design as the Eastland, now moored as a museum in Port McNicoll, Ontario. Using CGI technology, the producers superimposed an image of the Keewatin onto the Chicago River, replacing its name with the Eastland's.

This time around, Coppola and Moshman will also include newsreel footage of rescuers righting the ship and pulling bodies out of the water. The long-unseen footage was discovered in 2015 by Jeff Nichols, a UIC researcher and frequent Chicago magazine contributor.

Another difference between Coppola and Moshman's last Eastland project and today: All the survivors have passed away. The documentary does include two interviews with a then-10-year-old passenger named Libby Klucina-Hruby, conducted in the early 2000s.

Tragically, victims' families were never compensated. "First-generation immigrants often don't have the time or the money to fight long legal battles," Coppola says. They weren't inclined to share family sorrows with outsiders, either — another reason the Eastland is not well remembered.

The day before the documentary airs, though, there will be a commemoration at noon on the south side of the Riverwalk, just west of the Clark Street bridge, where the Eastland sank 104 years ago.