Today’s big non-Anthony-Weiner news: the brewing battle between the Chicago Public Schools, Mayor Emanuel, and the Chicago Teachers Union over CPS’s decision to rescind a four-percent automatic salary increase, which the mayor argues isn’t "automatic" at all. The argument by the Board of Ed and the mayor is basically "we can’t afford it"; for a good overview of the district’s financial troubles, I recommend Alison Cuddy’s interview with its president, David Vitale. CTU head Karen Lewis has stepped up the rhetoric, as the axing of the raise coincides with the push for a longer school day.

That got me to wondering what Chicago teachers have historically been paid, and whether today’s salaries are high or low by comparison. All the numbers below until this year’s are taken from Tribune reports. Keep in mind that news reports, when reporting teacher salaries, usually don’t break out pension contributions and other benefits. So these should be taken as ballpark figures; the pension situation is a whole ‘nother ball of wax.

The CTU got its first written contract with the Board of Education in 1966, under the leadership of the late John Desmond:

His tenure was marked by three-cornered battles waged by the union, the Chicago Board of Education and the Illinois General Assembly over the Chicago school budget. In his six years in office starting salaries for teachers went from $5,500 to $9,570.

In 1966, a starting salary of $5,500 was the equivalent of $38,358 in 2011 dollars. By 1972, the starting salary of $9,570 was $51,739 in 2011 dollars—the highest of the nation’s ten largest cities. His successor, Robert Healey, asked for a ten percent raise the next year, which the board’s chief negotiator called "insane"; they settled for a presumably less insane 6.3 percent raise to $10,000, or $50,892. How did a 6.3 percent increase turn into a drop in current dollars? That’s what happens when you adjust to the wild inflation of the 1970s. Accordingly, the CTU came back the next year and asked for a 12 percent raise to compensate.

What they got, in the wake of a 12-day strike, will sound familiar:

The resulting compromise, unlike those of years past, gives new teachers only a 4 per cent boost, putting the premium on education and experience. ("Teachers make threats pay with 90% pay hike since 1966," Chicago Tribune, 9/26/74)

By 1976, CPS faced a budget deficit of $70.8 million ($281 million in 2001 dollars); teachers were then making $11,000 ($43,683) to $22,600 ($89,750), and the school board passed an 8.5 percent salary cut.

1978: teachers were making $11,900 ($41,243) to $24,800 ($85,950), the latter for a teacher with a doctorate and 15 years of experience.

1979: the first time in 12 years that "a new contract ha[d] been agreed upon without a threatened or actual strike"—if you think the CTU head throwing around some rhetoric is hardball, keep in mind that during 1970s and 1980s strikes and threats of strikes were almost an annual occurrence—the CTU rallied with a substantial pay increase: over two years, salaries jumped to $13,700 and $29,268.

But that’s when inflation spiraled out of control. By 1979 dollars, $13,700 equals $42,641 in 2011 dollars. By 1980 dollars, it’s $37,569. The high end of the scale from the contract signed in October 1979, in 1979 dollars, is $91,095. In 1980 dollars it’s $80,261. Seriously, you can look it up.

1982: salaries ranged from $13,770 ($32,244) to $28,485 ($66,700). Not only did salaries stagnate, inflation wiped out any gains. To be worth $90,000 in 2011 dollars, the maximum salary would have had to been over $38,000. In terms of real salary, it was a significant drop.

1985: the minimum salary was $15,471 ($33,647) for a teacher with a bachelor’s degree. The maximum salary, for a teacher with a doctorate and 15 years experience, was $32,883 ($71,515). The average was $26,296 ($57,189).

1987: the same figures were $17,651 ($35,110) and $37,517 ($74,626); the average was $32,011 ($63,674).

1993: the minimum was $27,241 ($42,599); the maximum was $48,467 ($75,790); the article made a point to note that the starting salary for CPS was relatively high, while the maximum salary was relatively low. In other words, the pay range for Chicago Public Schools, compared to nearby regional districts, was narrow.

2000: the minimum was $35,000 ($49,928); the average was $48,879 ($64,140).

2003: the minimum salary was $34,538 ($42,415); the maximum was $61,451 ($75,466).

2007: the minimum was $40,405 ($43,034); the maximum was $72,583 ($79,102); the average was $56,000 ($61,030).

2010-2011: the CPS gives a starting salary of $50,577 for a first-year teacher with a bachelor’s degree. But that’s including the seven-percent "pension pickup," which comes from the Board of Education: it’s compensation, obviously, but not money teachers get right now.

Since that doesn’t seem to be regularly included in the salaries quoted by news reports, it’s probably better for comparison to subtract it, which can easily be done with the more detailed tables provided by CPS (PDF).

If we do that, the starting salary is $47,628. The maximum, for a teacher with 20 years’ experience and a doctorate, is $88,680 ($93,817 if you include the pension pickup). The average, according to the AP, is $69,000.

So what can we conclude? Chicago teachers’ salaries are relatively high by historical measures, but not unprecedented; the minimum and maximum salaries have been higher in the past, adjusting for inflation.

They’ve also been lower. By real wage terms, teachers made considerably less money in the 1980s, because previously high salaries not only stagnated, they didn’t remotely keep pace with inflation. (Which happened elsewhere; a 1987 paper in the Economics of Education Review found that starting teacher salaries in Michigan declined 20 percent from 1970 to 1980 when expressed in 1970 dollars [PDF]). And it was also the 1980s when the Chicago Public Schools’ reputation hit bottom; in 1987, Education Secretary William Bennett famously declared them the worst in the nation, a statement it’s taken CPS years to shake.

Very broadly speaking, from the mid-1970s to the early- to mid-1980s, Chicago teachers lost, in real wage terms, the salary gains they’d made under John Desmond’s leadership. From the mid-1980s to now, they seem to have made back most of those gains.

At the same time, labor tensions, comparatively speaking, have cooled. Strike threats and strikes aren’t as regular as they were during the 1960s and 1970s.

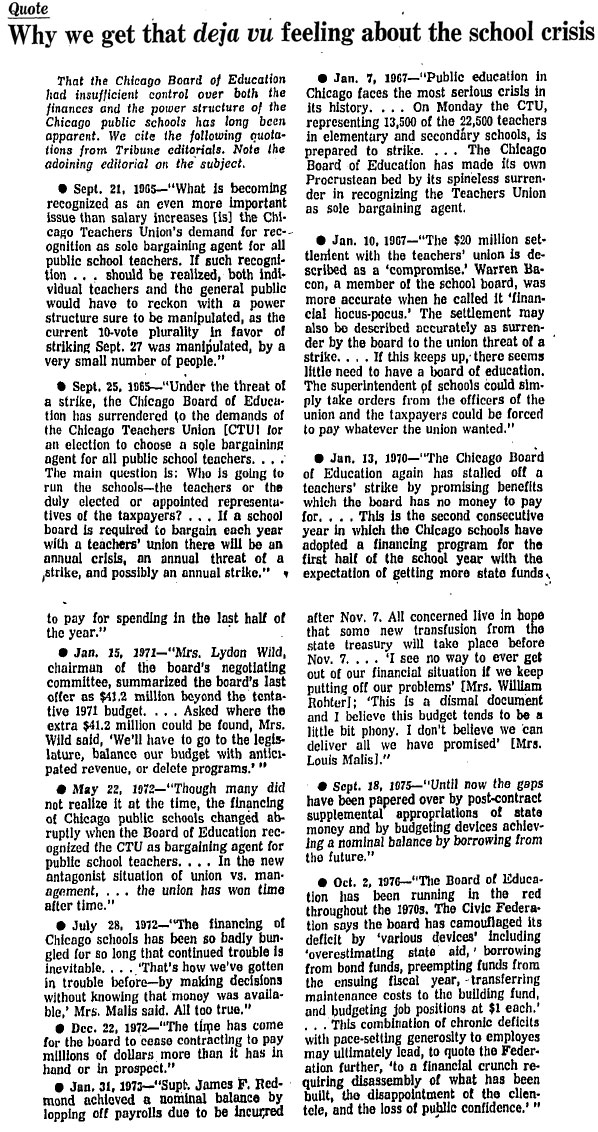

What hasn’t changed, and probably never will: the feeling that CPS is always on the brink of disaster. Here’s the Tribune editorial board in 1980, about four months before I was born, quoting itself from 1965 through 1976: