On June 6, 1892, the El (or "L," if you prefer—I do not, but recognize it has properly been "the 'L'" since the first day) made its debut, making the run from 39th to Congress in 14 minutes—a few minutes longer than it takes the current Green Line trains to go from Indiana to Roosevelt, though it ran more frequently for most of the day, including every three minutes at rush hour. On June 7, the Tribune published a lengthy report of the "L's" first day. For the most part, it went smoothly. The same could not be said of public transportation more generally in Chicago, as detailed in a wonderful, lengthy piece by Robert Loerzel in the Reader.

RUNNING ON THE "L."

—

FIRST TRAIN GOES THROUGH IN FOURTEEN MINUTES

—

Initial day of the Real Rapid Transit an Encouraging One for Officers of the Road and South Side Residents—Cars Well Filled and Not a Hitch Occurs to Mar the Inauguration of the Long-Looked-For Service—Incidents of the Day—How Trains Will Run.

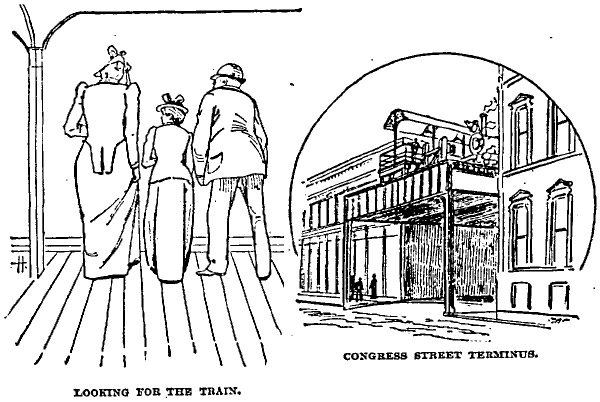

Chicago's elevated railroad is in operation. At 7 o'clock yesterday morning the first north-bound train left Thirty-ninth street and in the four coaches were twenty-seven men and three women. Fourteen minutes later the train was at Congress street, and giving two minutes for changing engines it started on the return trip at 7:16. Thus was Chicago's new elevated road thrown open to the public. There was no brass band, no oratory, no enthusiasm, but the opening was a decided success just the same.

During the day the trains were crowded, partly by persons who desired to make their first run over the new road. Those who made observation trips early in the day were well repaid for the trouble, for the people living on either side of the track had seemingly forgotten the warning about the start, and the passengers saw bits of domestic life, usually hidden from the gaze of passing crowds. Late risers were confronted with the alternative of lying in bed till darkness came again or watching until there would be no train in front, giving them the opportunity of pulling down the all-concealing blind. Servant girls, cooks, and chambermaids left their work to watch from back porches the fast-flying trains as they went by, and late breakfasts were probably explained on that score.

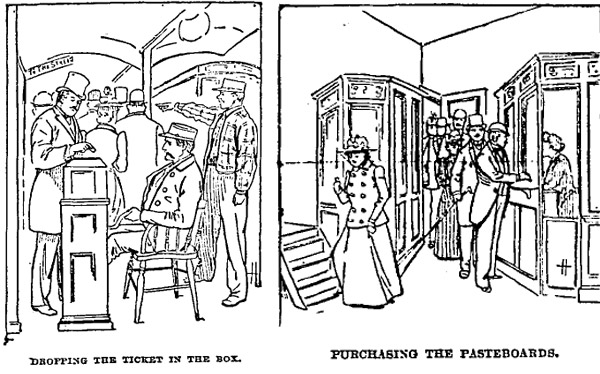

How many people rode on the "L" road during the day was past estimating by the officers. The tickets furnish little in the shape of a clew to work on, for, though numbered consecutively, they were scattered at the stations along the line, and until the ticket sellers make a report the number sold cannot be learned, and even then the number dropped in the boxes must be counted before the actual number can be ascertained. But, however many there were, nearly every train during the daylight hours was filled, and the familiar sight of people hanging to straps was witnessed between the hours of 5:30 and 6:30 o'clock, when the stores and offices closed and employees started home.

The down trains in the morning up to 9 o'clock, and even after, were well patronized, and every passenger wore a pleased and satisfied expression. To many it was the first experience in really rapid transit; to others, who have long been familiar with elevated trains in New York, comparisons were made, which were at least complimentary to the local road. No little interest was displayed in the rate of speed, and open watches were studied with as much care observing the time consumed between stations as though the Derby was being run instead of the initial trips on the "L" road. The new sensation of being whisked down-town from Thirty-ninth street in fourteen minutes, including all stops, so impressed many of those occupying seats that it served to loosen their tongues, and apparently sane gentlemen, entire strangers to one another, freely discussed the novel, but none the less satisfactory journey without the usual formality of introductions.

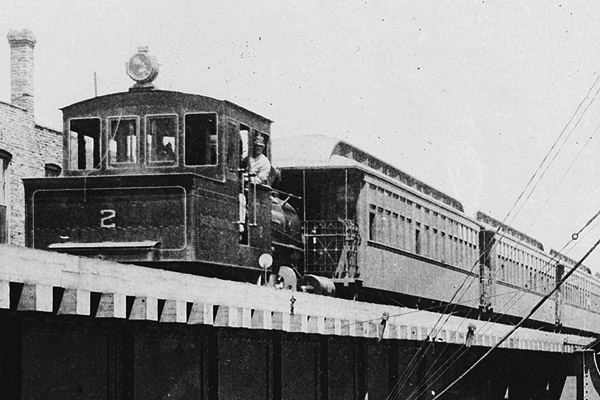

There was not a hitch during the entire day. The little engine would come puffing up to the stations, stop at the spot where the sign is placed without a perceptible tremor in the cars behind, start up again as easily as it had stopped, and go running away from the cable trains on State street or Wabash avenue. The running was smooth, and the elevated structure bore the strain with little tremor. Inside the cars there was less noise than in a cable car, and there were no trains or heavy wagons to get in the way and cause a vexatious delay. It was nice and pleasant, with a good breeze and an occasional view of the blue waters of Lake Michigan through the east and west streets.

And then the coaches. New York has never seen such gay ones as those put in service yesterday. They have an outside color of pale olive green, and inside they are finished in oak and cherry in natural colors. The seats are roomy and comfortable, with cushions, the ones at either end, running lengthways of the car, being divided by arm rests in cherry. Eight double seats are in the center of the car, the same as in an ordinary railroad coach. These have high backs, and between each there is a small mirror set in the side of the car between the windows. The windows are wide, and at present have the added novelty of opening easily. The doors are novelties in their way. They are of the double sliding pattern and when one is pushed back both open. The platforms are roomy and are provided with gates which are opened by the gateman when the cars come to a stop and closed and locked before the strain starts again. The ceilings of the coaches are decorated in a variety of ways. Some are of hardwoods, while others are covered with a coarse canvas fastened with large brass-headed tacks and colored dark blue, brown, and red. There are straps of the same pattern furnished by Mr. Yerkes.

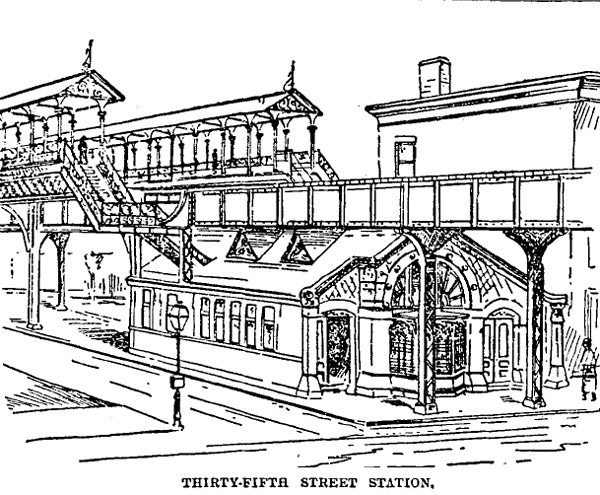

Everything about the line denotes solidity, and at the same time an attempt to make the equipment and the stations as handsome and convenient as possible. All the station houses so far completed are built underneath the track, though this will be impossible where the road runs in streets as it will south of Thirty-ninth street. They are of brick and terra cotta with all the woodwork in oak. One ticket seller and one collector will transact the ticket business for both north and south bound trains. The passengers coming in, pass the windows of the ticket office, then the ticket box where the tickets are dropped, and then go through a passage way to the stairs. At the head of the first landing the stairs divide, the one for the down town trains being on the east and the one for the south bound trains on the west side. The stations have a wainscoting of enameled brick to a height of six feet and are plastered above. The stairways have a graceful iron covering which extends above both platforms. A platform-man is stationed on each platform to keep the crowds moving aright and there is a janitor in service at each station. Toilet-rooms have been provided for men and women at each of the stations, except the one at Congress street, which is located in a building facing Congress and Wabash avenue.

There is one particularly pleasing feature about the new "L" which strikes passengers who have been accustomed to ride on the Manhattan Elevated. The guards, possibly through ignorance of the code of ethics which is recognized by all "L" guards, pronounce the name of the street where the next stop will be made in a plain and distinct tone of voice. The beief is entertained by some of yesterday's passengers that this strangeness will wear away in the course of a week or two.

For even the short distance now carried by the Elevated the shortening of time is marked. The run from Congress to Thirty-ninth street is made in fourteen minutes, about half the time required by the State street cable line. The stops are further apart than those made by the cable trains and no more time is lost in stopping than by the street cars. As the line is extended south the saving in time will become more apparent.

While much less noisy than the steam cars on the surface railways, the moving trains make themselves apparent to those who occupy buildings adjoining the tracks. Said a teacher in the Haven Public School at Wabash avenue and Fifteenth street:

"The noise and confusion in our schoolrooms are simply dreadful and distracting in the extreme. For a long time we have had the clanging bells and the steady rumble of the cable cars in front of the building; on both sides of us in the rear, facing State street, an extensive junk shop, where the principal business seems to be the purchase and crashing deposit of old iron; no boiler factory has yet been established in the neighborhood, but now we have the elevated road which adds its share of noise to the distraction of teachers and scholars alike."

The equipment consists of twenty engines and sixty coaches. Eighteen trains are run during the busy hours, the two remaining engines being used as relays at each end of the line. The trains are run with three or four coaches each. A train running into the station at either end of the line is uncoupled from the engine and the relay engine is coupled on the other end. In this way each engine is given from three to ten minutes at each end of the run for oiling or renewing fires. The water tank and coal bunkers are located south of Thirty-ninth street.

Something should be done by the managers of the South Side Rapid Transit company to relieve the congestion at the Congress street station. As matters now stand not only is no provision made for the handling of a crowd of passengers of any dimensions whatsoever, but the arrangement of the passages leading to the platform of the station is such as to preclude the possibility of accomodating a rush. The first stairway leading from the street is broad enough, but after the second story of the building is reached quite a difficulty is encountered. Passenges fall into line and then force themselves into a narrow passage leading to the ticket window, after which they take a tack to the right and ascend the stairs leading to the platform where the train is to be taken.

In case of a crush at this narrow passageway—and there is always a crush when forty or fifty people come into the station at once in a hurry to take a train—the movement is so slow that a jam inevitably results, the consequence being that many persons must necessarily miss a train they could otherwise have taken. It is admitted by the elevated railroad people that the arrangement is a bad one, but promise that everything will be remedied before the World's Fair crowds come upon them. This, however, is hardly enough. A change just now would be welcome and result in increased passenger traffic. Many people yesterday, not caring to brave the crush at the ticket-seller's window, became disgusted and went away to take the cable cars, which, however crowded, admit to the possibility of being boarded.

The regular schedule put into effect yesterday gives a splended service. There is no last car to be "chased," as the train service is kept up during the twenty-four hours. Beginning at 12 o'clock, midnight, trains are run every twenty minutes until 5 o'clock, every fourteen minutes between 5 a.m. and 7 a.m., every six minutes between 7 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. every three minutes from 8:30 a.m. until 9:30 a.m., every six minutes from 9:30 a.m. to 4 p.m., every three minutes from 4 p.m. to 6:30 p.m., every six minutes from 6:30 p.m. to 10 p.m., and every fourteen minutes from 10 p.m. till midnight.