This week the Reader's Mick Dumke and Ben Joravsky have their second look into the mayor's schedule: who he meets with, what they do, and what their interests are. One theme running through the piece is that a lot of them are not just Republicans, but active opponents of Democrats—such as Citadel CEO Ken Griffin, who was recently profiled in Chicago. He plays both sides, if by "both sides" you mean conservative Republicans and centrist Democrats:

Griffin has hedged his political bets, giving money to politicians on both sides of the aisle, including Representative Paul Ryan and Senator Tom Coburn, both Republicans, and the Democrats Rahm Emanuel (both for Congress and for mayor) and Senator Evan Bayh. Nonetheless, the preponderance of the donations has gone to Republicans.

At a more local level, Griffin has not only donated to Emanuel; he's also donated to Bill Brady for his campaign against Pat Quinn; Rod Blagojevich (twice!); Mayor Daley; and $445,000 to various state Republican legislative candidates in 2010.

Griffin didn't just support Illinois Republicans specifically. He backed them with more general support: "$140,000 in October 2010 to Two Party System, a political action committee that fights 'Illinois’ one-party system' by supporting the state campaigns of Republicans and independents." But two-party proponents have their limits. As Dumke and Joravsky write:

A couple weeks after the chat with Satter, the mayor set aside an hour for one of his favorite Republicans, Ken Griffin, CEO of Citadel Investment Group, a hedge fund. The Griffin household was particularly generous to Mayor Emanuel's campaign: Griffin himself donated $100,000 while his wife, Anne Dias-Griffin, who also manages a hedge fund, gave another $100,000. Other Citadel employees chipped in $39,000 more.

The suggestion is that, on one hand, Emanuel is peeved by partisan attacks on his recently-former boss and the administration he played such a crucial role in; on the other, he makes time for the people funding those attacks. (Though Emanuel does seem to have some limits, putting Joe Ricketts on watch after that row.) It's worth noting, but it's also worth considering how Griffin is, in some ways, stuck in the same loop. For all his support of local Republicans, and a PAC seeking to wrest Democratic control from the state's "one-party system"—true as far as it goes, which is from Chicago out to some, but not all of the suburbs—he has to pour hundreds of thousands of dollars into the campaigns of his frenemies. I think the saying is "keep the people who you tend agree with close, keep the people you usually don't agree with closer."

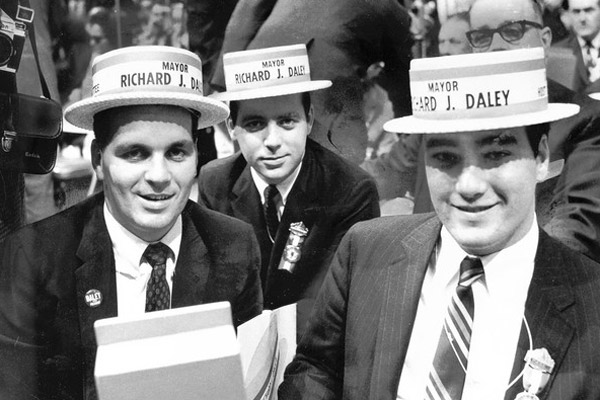

And it's an old system that Mayor Daley—the one who invented being Mayor of Chicago—perfected. In American Pharaoh, Elizabeth Taylor and Adam Cohen describe the hold the mayor had on Chicago's very Republican business community:

The main difference between Daley's 1959 campaign and his first run, four years earlier, was his newfound support in the business community. Chicago's business leaders had a long history of opposing the Democratic machine. It was, in part, simple political partisanship. Leading businessmen in Chicago, as in most of the country, were heavily Republican. Their interest in low taxes also put them at odds with the machine, which thrived on padding payrolls and handing out sweetheart contracts.

[snip]

But in his first term in office, Daley had skilfully won the Republican business establishment over to his side. The most important factor was his vigorous promotion of downtown interests. Daley's 1958 redevelopment plan, which had been all but drafted by the Central Area Committee, made clear to downtown businessmen that the Loop was his highest priority.

The CAC, Taylor and Cohen write, "were the most powerful men in Chicago. They were overwhelmingly Republican, and had given large amounts of money to Kennelly, Merriam, and most other reformers who challenged the machine. Urban renewal was Daley's opportunity to reach out to these powerful Republicans…."

But they also had a hold on him. Bipartisanship cuts both ways. UIC might have been placed in Garfield Park—and perhaps could have served as an economic and cultural anchor for the community—had the trustees who voted on the location, and the community, had their way. But the CAC wanted it close to the Loop, and the machine quashed the Garfield Park plan. The placement of UIC in the Harrison-Halsted community became one of the more infamous instances of urban renewal in the city's history, displacing tens of thousands of residents.

It didn't stop there. I refer to this piece over and over again, but David Moberg's "The Fuel of a New Machine" represents the modernization of the machine Daley built and passed down to his son:

[Richard M.] Daley's biggest contributor is J. Paul Beitler, a major downtown developer. Beitler, a Republican who lives in Winnetka, thinks the downtown area owes nothing to the rest of the city. He refers to the city's neighborhoods as "the suburbs." He thinks the opening up of political debate that followed the election of Harold Washington has deterred international investors from participating in his big projects (despite evidence that the city is in the midst of one of the biggest downtown building booms in its history), and he sees Daley as returning the city to a period of "stability" much like the reign of his late father.

Even then, it's not just a matter of Democratic party rule; as Moberg points out, during the transitional period between Daleys, Chicagoan Jim Thompson, as governor, worked city business interests in a similar fashion.

Political developments at the national level, where Congress is now more fractious than Chicago during the Beirut-by-the-Lake years, have led to fretting about bipartisanship and comity. Cities like Chicago give some clues as to how the other extreme works, and doesn't.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune