Last week, guitarist Pete Cosey died in Chicago, where he was born and spent most of his life, serving as a vital session musician not only at Chess but also with Miles Davis, his career spanning a wide spectrum from R&B and blues to wild '70s jazz, from Chuck Berry to Muhal Richard Abrams. As Peter Margasak points out in his obituary, Cosey was a genius, but never broke through as a solo artist in the way he succeeded as a session man:

After Davis broke up the band in 1975 and went into semi-retirement, Cosey was never able to build the solo career he so richly deserved. He used his guitar like an abstract expressionist painter, creating thick, richly textured solos with fierce rhythmic power, dazzling colors, and nonchalant violence. He continued to appear on records here and there, including Herbie Hancock's Future Shock and an album with Japanese saxophonist Akira Sakata, but he always seemed to be planning his own next project, which never quite materialized.

Margasak wrote two columns about Cosey for the Reader while he was alive; in one, Cosey discusses how his ecumenical relationship to music wasn't shared by the people he worked with:

"There was a great division in those days, I'm sorry to say," says Cosey. "The blues people and the jazz people did not get along. I don't know whether it was jealousy or not, but it wasn't like it is now where people have an appreciation for all styles of music."

Most notorious was Howlin' Wolf. Cosey's experience and lack of dogmatism made him a perfect guitarist for Chess's late-60s attempt to keep up with the times, and Cosey was a vital part of the classics Electric Mud with Muddy Waters and The Howlin' Wolf Album, bringing in his jazz experience and effects pedals to add a psychedelic tinge to the blues masters' sound.

With the distance of time, The Howlin' Wolf Album doesn't sound that psychedelic. It's not like Chess tried to turn Howlin' Wolf into Jim Morrison. It's still blues, but with more guitars, more bass, and more forward, elaborate drumming. The flute's a bit psychedelic. But Howlin' Wolf hated it. Hated the album; hated Cosey's gadgets; hated Cosey's weird hippie hair.

“I had a really long beard during those days,” he told writer Bill Milkowski in 2007. “It was, like, down to the navel, and I’d sometimes braid it. So on one occasion during the session, Wolf walks up to me and says in that raspy voice of his, ‘Why don’t you take them wah-wahs and all that other shit and go throw it off into the lake on your way to the barbershop?’ I mean, he just wiped me out with one stroke, man! Covered all the territory—the long hair, the beard, the wah-wahs and the whole deal.”

(Muddy Waters wasn't much into Electric Mud, either: "Several years before he died, Waters was more direct, calling the album 'dog s—.'")

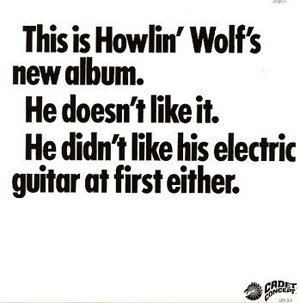

Left with an album that was too forward-looking for its own creator, Chess took a curious approach to its marketing. The cover is so distinctive that I bought it the first time I saw it; it jumps out of any record bin it's in, though that didn't do much for sales or its reception. It's still divisive, and wasn't released on CD until 2007, almost 40 years after it was recorded. It's simultaneously one of the great failed experiments in both music and marketing.