As part of WBEZ's outstanding Race Out Loud series, Dan Weissmann filmed a time-lapse video of the Red Line, noting how it reflects the racial divisions in the city. It was familiar, as a former resident of both Hyde Park and Woodlawn, to see the patterns etched into my brain from traveling to Garfield or 63rd and back. And Weissmann's piece echoes one of the seminal documents of race relations in the city and the Chicago school of sociology: "The Negro in Chicago: A Study of Race Relations and a Race Riot."

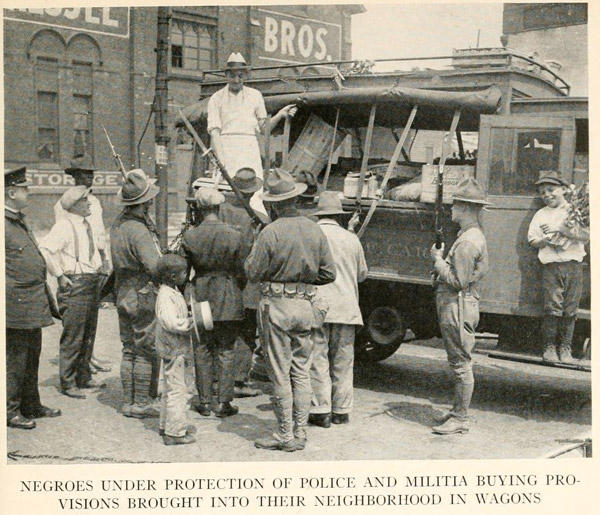

The lead author was Charles S. Johnson, who was born to a mixed-race couple in far southwestern Virginia, arrived in Chicago with his parents early in the Great Migration, studied at the University of Chicago as an undergrad, and returned after World War I as one of the early students in the school's burgeoning sociology program, which would soon redefine our understanding of the city through its synthesis of fieldwork and data. (The data-driven journalists of today owe a debt to Johnson and his peers; The Negro in Chicago, in particular, is full of exquisite maps of the riot and social conditions in the city.) Johnson finished his PhD in 1918; the race riot occurred the next year, as Johnson was working for the National Urban League, which he would go on to become the research director for.

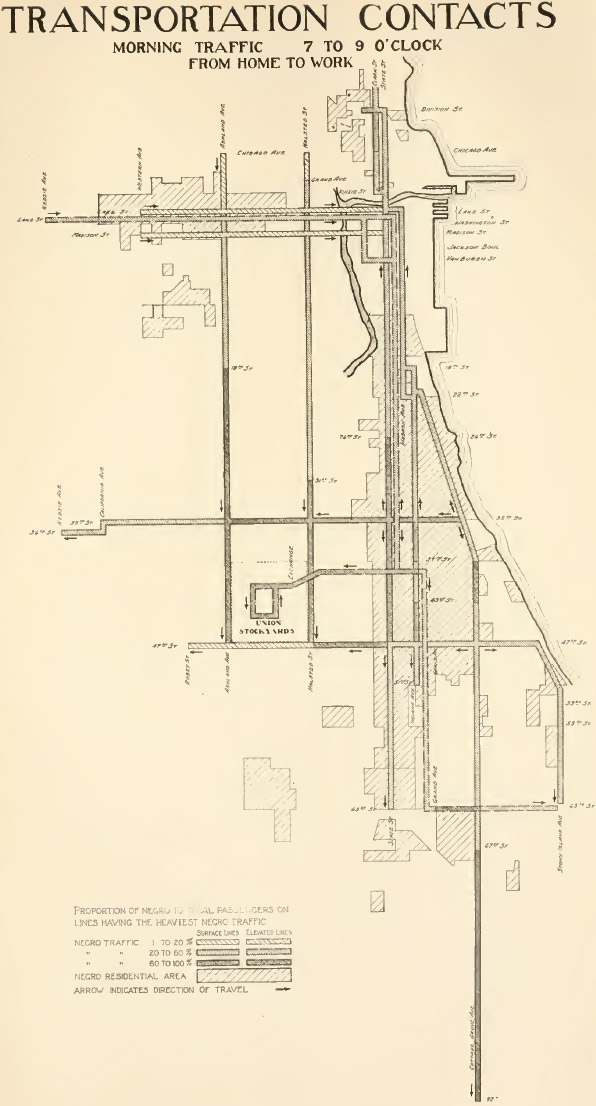

In the chapter "Public Opinion on Race Relations," Johnson captured a moment on public transportation much like that recorded by Weismann; only the geography has changed.

A second phase of the situation, and the one that causes more inutile railing than any other, is the crowding into the street cars of colored people. Well, they must ride on street cars, if only for the reason that most of them live remote from their work. Even the North State Street line, that used to be considered the special conveyance for "the quality," has come to be known as the "African Central." If you can't stomach it, you'll have to walk. They won't.

(See below for a map, from The Negro in Chicago, depicting segregation on public transportation in 1922.)

The Negro in Chicago, written comparatively early during the Great Migration, was a prescient warning: "measures involving or approaching deportation or segregation are illegal, impracticable and would not solve, but would accentuate, the race problem and postpone its just and orderly solution by the process of adjustment." But as it was being written, other Chicago academics were working on undermining the recommendations of the Crime Commission; their work would fix those patterns in law and economics, making segregation both legal and practicable.

In his new book Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities, Carl H. Nightingale traces the phenomenon back to Sumer, but narrows down to a focus on Johannesburg and Chicago. In the former, segregation was explicit. In the latter, it couldn't be; in 1917, the NAACP challenged a segregation ordinance in Louisville, leading to the decision in Buchanan v. Warley, in which "a multiracial team of attorneys led by a black professional had forced a white supremacist judiciary to choose between racism and a basic premise of laissez-faire capitalism—and property rights won out, at least in the case of neighborhood segregation." But there was profit to be had in racism, and it would soon find ways around "laissez-faire capitalism," with curious allies in the Progressive movement.

About a decade before Buchanan, the National Association of Real Estate Boards grew out of the Chicago Real Estate Board; it would coin the term realtor, and set professional standards for the sale of real estate (now the National Association of Realtors, it remains one of the most powerful lobbying organizations in the country). In the 1920s, its general counsel was Nathan William MacChesney, a former president of the Illinois Bar and a co-founder of Northwestern's Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. MacChesney was considered a progressive; in the words of David Roediger, "the principal figure in the 'progressive' reform of real estate."

The NAREB, and MacChesney, had a powerful progressive ally in Richard T. Ely, then an economist at the University of Wisconsin; in the mid-'20s, he moved to Northwestern. Ely, a proponent of the Social Gospel, had ties to Chicago progressives—he was the first president of the American Association of Labor Legislation, a "useful synechodoche for progressive economics," which had Jane Addams on its board.

But Ely and MacChesney also represented troubling strains in the Progressive movement, as Nightingale writes:

Though neither elaborated a full-fledged theory of race in print, both had swum in a similar soup of racialized and imperialist reform politics for most of their careers…. several times [Ely] advocated measures to slow down the reproduction of people he deemed part of the "sad human rubbish-heap"—the "feeble-minded," welfare recipients, and criminals…. MacChesney, whose list of board memberships in reform organizations was legendary, likewise wrote a eugenical tract advocating sterilization programs for the mentally ill and for prisoners.

Ely was a segregationist who disapproved of segregation, a racist who blamed white racism for the status of blacks in the south. In his textbook Outlines of Economics, Ely wrote that the "negro problem to-day… is due in some degree to the economic inertia and shiftlessness of the negroes themselves," but also that it was due "in part to race prejudice of their white brethren" while acknowledging the ongoing effects of slavery. He praised his country's "marvelous ability to assimilate rapidly people of diverse races, tongues, and religions, amalgamate them and stamp them with the characteristic qualities of the American," but feared for our ability to do the same with the next group of immigrants (emphasis mine):

We have failed, however, to amalgamate the Negro and the Cinese; the incidental feature of a dark skin creates especially difficult problems; and it is this fact which makes it undesirable that Japanese, Chinese, or Hindu laborers should settle here in large numbers, particularly in separate "colonies." Despite the high quality of some of these peoples, it is conceivable that they might come to this country in sufficient numbers to create a problem similar in character in gravity to the negro problem; and if investigation show that there is real probability of such a result, they should be excluded, even though the danger be attributable to race prejudice of the natives rather than the clannishness and exclusiveness of the immigrants.

3. In the main, however, the traditional policy of this country has been "to improve rather than to check immigration," and the burden of proof is upon those persons who would restrict immigration by arbitrarily limiting the number of immigrants.

It's a very narrow eye Ely tries to thread: he's not opposed to dark-skinned immigrants per se; in fact, some of them are "high quality"; he is opposed to separate "colonies"; yet the fear of racial violence—the fault of the natives, no less—is such that they should be excluded from the country, as long as the burden of proof is on "those persons who would restrict immigration."

MacChesney, in a real-estate law textbook edited by Ely, echoed a similar theme, as Nightingale writes:

Because blacks have "the same prerogative" to exclude whites from their own neighborhoods by restrictive covenant, MacChesney argued, these covenants involved "no discrimination within the civil rights clauses of the Constitution." Such airy denials of the existence of institutionalized inequality had their roots in the "separate but equal" doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson.

In 1924 MacChesney warned in NAREB's code of professional ethics that realtors cannot introduce "members of any race or nationality… whose presence will be clearly detrimental to to property values in that neighborhood"—the microeconomic version of Ely's macroeconomic dictum. In 1927, Corrigan v. Buckley gave the Chicago Real Estate Board the legal cover it needed to enshrine such a covenant, and MacChesney drafted the now-notorious standard restrictive covenant.

The Great Migration continued to increase Chicago's black population, but the city now had a powerful tool to control it. By 1940, according to historian Beryl Satter, Chicago had more racial-deed restrictions than any other city in the country; half the city was covered by such covenants. Nor was it limited to Chicago, Satter writes: "Real estate boards across the nation recognized CREB's pioneering work in maintaining all-white communities and looked to CREB for advice as they crafted their own racially restrictive plans." The fear that Johnson—himself a child of the Great Migration—and his colleagues had warned about in 1922 came to fruition, encoded into law.

Images: Archive.org

Comments are closed.