Photo: Zbigniew Bzdak / Chicago Tribune

Carlos Patterson, 13, right, and other 7th grade students on one of the final days of classes this June at West Pullman Elementary, which is being closed by Chicago Public Schools.

The other day my colleague Carol Felsenthal wrote about Deborah Quazzo, who is replacing new Commerce Secretary Penny Pritzker on the Chicago Public Schools board, and why she's a controversial choice. Felsenthal focuses on how Quazzo, one investment banker from wealth is replacing another, tapping into the class and privatization issues that have surrounded school closings, charter schools, and so forth.

The wealthy have always had a hand in driving American public education: John D. Rockefeller drove the public educational system in the South; Andrew Carnegie stabilized the early public library system. In the 1920s, Rockefeller's General Education Board stirred a fight in Indiana between township trustees and external forces that desired a statewide public education system controlled at the county level. See if this sounds familiar: "The idea of running the schools like a modern business was very appealing in the 1920s"; "lower costs and increased instructional outputs were the twin benefits promised"; "the further one moved away from the professional and more distant educators and closer to the local elected school officials and citizenry the less enthusiasm was to be found." (The GEB's efforts in Indiana failed, and Rockefeller's reform efforts never gained the traction in the Midwest that they did in the South.)

That Quazzo has invested time and money in school reform is not particularly unusual. More so is her day job at GSV Advisors:

[I]n many ways a "modern merchant bank"—transforming the legacy concept of private equity capitalization that helped fuel the Industrial Revolution. Rather than manufacturing, we're focused on the Education champions of today and tomorrow—the pioneers of technology, intellectual property, communities and social marketplaces, innovative learning environments and institutions, influencers of academic policy, and so on.

They also "aspire to help catalyze interactions within the education ecosystem to foster innovation and network connections." That may require some explanation. Here's one:

In the venture capital world, transactions in the K-12 education sector soared to a record $389 million last year, up from $13 million in 2005. That includes major investments from some of the most respected venture capitalists in Silicon Valley, according to GSV Advisors, an investment firm in Chicago that specializes in education.

The goal: an education revolution in which public schools outsource to private vendors such critical tasks as teaching math, educating disabled students, even writing report cards, said Michael Moe, the founder of GSV.

(Actually, Moe founded GSV Asset Management and GSV Capital, which are sister companies to GSV Advisors; Quazzo is the founder and managing partner of GSV Advisors, to which Moe serves as an advisor.)

Michael Moe is particularly hard-charging on the privatization of education and the opportunities for venture capital in that industry. On July 4, 2012, Moe was the lead author on a GSV Asset Management white paper (h/t @sethlavin), "American Revolution 2.0: How Education Innovation Is Going to Revitalize America and Transform the U.S. Economy." It's a punchier read than most white papers. For instance, the idea that a revolution in education is supposed to prevent revolutions of other kinds, like ones in which taxes become more progressive (emphasis theirs):

We need a revolution, not an evolution in education. Simply stated, we don’t have time to let incremental progress be our goal. Occupy Wall Street (“OWS”) and adjacent uprisings have powerfully demonstrated that a large and growing segment of American society doesn’t believe that they are participating in the future. Aristotle observed, “Inequality is the parent of revolution.” The “1% vs 99%” that OWS blames for all of America’s troubles actually contains a substantial kernel of truth.

[snip]

It should not be lost on us that revolutions are actually a fairly common occurrence in modern society. The most recent prominent example is the “Arab Spring,” but since 1900, there have been over 250 governments overturned by revolutionary action.

Joe the Plumber is right in that redistribution of wealth is not a sustainable economic philosophy, nor is it an American one. There is no example in history of any nation taxing itself into prosperity. However, when approximately 50% of adults don’t pay any federal income tax, the seeds of class chaos could easily result in a Robin Hood State instead of addressing the real issue of preparing people to be productive in the world we are in. The revolution America needs today is not against an oppressive monarchy, but rather against an educational system that has equally oppressive effects.

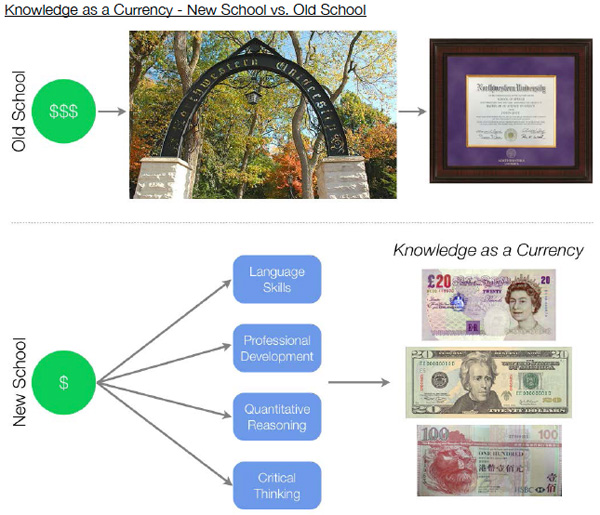

The posited cure to head off revolution is to address the "gigantic mismatch between the skills of our people and the jobs being created," because "the flight is to high quality human assets rather than financial assets and in this new reality, knowledge is the tangible currency." It has graphics for visual learners. Look out, Northwestern! They're coming for you!

Around the same time, Quazzo was the lead author on "The Fall of the Wall: Capital Flows to Education Innovation," which is less of a manifesto and more a nuts-and-bolts look at the education industry and the opportunities and challenges to companies and investors. In some ways, the report is optimistic:

Investment volume in 2011 exceeded peak 1999 – 2000 [i.e. Internet boom] levels, but is differentiated from this earlier period by entrepreneurial leaders with a breadth of experience including education, social media and technology; companies with vastly lower cost structures; improved education market receptivity to innovation, and elevated investor sophistication.

But "clouds and impediments remain on the horizon as noted":

Through the second half of 2011, we conducted interviews (July/August 2011) and polls with numerous constituents in education. It was clear to us from these dialogues and inputs that more capital is available if onerous conditions in both K-12 and higher education could be alleviated. Some innovators have created successful “work-arounds” to seemingly intransigent obstacles but that is still the exception and not the rule. Some of the work-arounds– such as freemium models – remain untested as viable long term business models

This investment volume is attributable to a "confluence of catalysts," a combination of political, financial, technological, and social trends, including "budget constraints drive changes in approach"; "federal 'Race to the Top' and NCLB incentives"; "charter schools as early adopters"; "Teach for America elevating education as elite career path"; "foundations as change agents"; "Tier I VCs entering and re-entering the market"; and so forth.

The report forecasts "potentially huge end markets": "Education represents nearly 9% of GDP, but less than 1% of both venture investments and public market capitalization." It's "clearly ripe for disruption, but obstructed by ingrained parties that may be resistent to change."

One of the IPO success stories touted in the report is K12, Inc. ThinkEquity, co-founded by Quazzo, was one of its underwriters; it's listed among the GSV Advisors team's previous partners (as is Franklin Covey, whose partnership with CPS was the subject of an interesting recent DNAInfo story by Chloe Riley).

And K12, Inc. is an example of the role of charter schools as early adopters, potentially huge end markets, and regulatory resistance, if a somewhat extreme one. The New York Times did a lengthy and kind of surreal investigation of K12, the biggest online-school company in the country; its biggest school is Agora Cyber Charter School in Pennsylvania, but it's not limited to there: "Another way K12 maximizes its income is to establish schools in poor districts, which receive larger subsidies in some states. The company administers one of K12’s newest schools from Union County, Tenn., a mountainous Appalachian enclave where nearly a quarter of the residents live in poverty."

It broke through in Pennsylvania the old-fashioned way:

In Pennsylvania, where K12 Inc. collects about 10 percent of its revenues, the company has spent $681,000 on lobbying since 2007. The company also has friends in high places. Charles Zogby, the state’s budget secretary, had been senior vice president of education and policy for K12. In a statement, Mr. Zogby said he still owned a small number of K12 shares, but did not make decisions specifically affecting online schools.

(Chicago has one virtual charter school, which enrolled 590 students in 2012; it serves a population with a lower percentage of low-income students than the average CPS school.)

The GSV consortium is not the only player in the field, which is expanding, as Lee Fang writes in The Nation, citing Moe:

A combination of factors has made this year what Moe calls an “inflection point” in the march toward public school privatization. For one thing, recession-induced fiscal crises and austerity have pressured states to cut spending. In some cases, as in Florida, where educating students at the Florida Virtual School costs nearly $2,500 less than at traditional schools, such reform has been sold as a budget fix.

What does this mean for Chicago Public Schools? Likely not that much. Power flows from the administration and CPS to the board, not the other way around; Quazzo is merely one vote, and comes from a similar background as Penny Pritzker, who was heavily invested in the school reform movement. Instead, it's more interesting as a look at the broader state of the education industry—how the rise of the technology and financial sectors, along with governmental interest in privatization during a time of strict budget cuts have integrated with school reform, creating a burgeoning market that's not limited to the hip MOOCosphere, but is making inroads in public education.