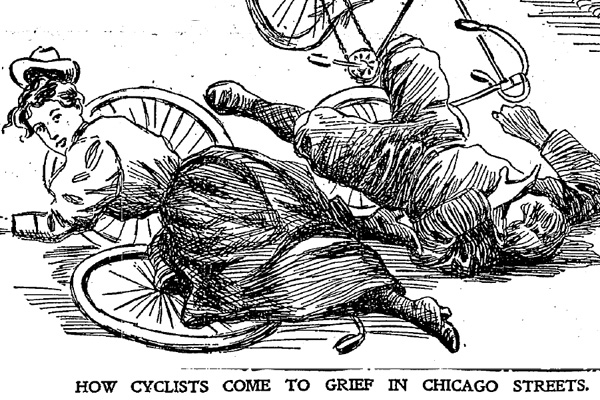

Illustration: Chicago Daily Tribune, 1897

New York is still going through its bike-share freakout, and its journalists are topping even the best contributions by Chicago's finest cranks. The Wall Street Journal's Dorothy Rabinowitz, an editorial board member, gave an improv-level rant about their "totalitarian government" and its "ideology-maddened traffic commissioner" who are in thrall to the "bike lobby… an all-powerful enterprise." Your move, John Kass!

Rabinowitz's line about the ALL-POWERFUL BIKE LOBBY has been good for some giggles—there are some effective, though generally regional, advocacy organizations like the Active Transportation Alliance, but it's not like there are power-suited fast-talkers wheeling up to Capitol Hill to pitch derailleur subsidies with the many millions they receive from Surly and Chrome.

There's no lobby like there used to be, at least. My friends and I were discussing Rabinowitz's wonderful performance, and one of them, a historian, pointed out that the League of American Wheelmen was once the most powerful transportation lobby in the country—a big advocacy group that could draw 20,000 to its annual convention, lobby legislatures for road building, and help elect a mayor of Chicago.

It being Chicago as much then as now, he returned the favor in kind.

That mayor was Carter H. Harrison, the five-term, 22-year mayor of the city, who died in 1953 on Christmas Day at the age of 93. Harrison was an immensely powerful old-school politician, the son of a Chicago mayor. Col. Robert McCormick considered Harrison the "father of North Michigan Avenue" for his improvements to the chaos of teamster traffic that blocked north-siders from the not-yet-Magnificent Mile, reminded the Cliff Dwellers Club, shortly before the ex-mayor's death, of Harrison's bike advocacy.

When he died, the Tribune wrote that "father and son each served five terms as mayor of Chicago—a record unparalleled in any large American municipality. The Harrisons formed as near a political dynasty as is possible in a republic." (Richard J. Daley was elected two years later.) Then, before mentioning his political wars with govenor John P. Altgeld and Charles Tyson Yerkes—the latter over long-term transportation infrastructure leases, in case you were wondering if anything new happens here—and before mentioning that he closed the world-infamous Everleigh brothel and almost ran for vice president, his obituary covered Harrison's legendary cred as a cyclist:

Harrison received many votes from cyclists, for their sport was very popular at the time and he excelled in it. Campaign lithographs pictured Harrison on his cycle with the inscription "Not the Champion Cyclist but the Cyclists' Champion."

When Harrison was running for mayor, the Trib wrote that "Candidate Harrison has long been a bicycle rider. He rode a great deal last year. Altogether he made over 4,400 miles and covered twelve centuries [100 mile rides]," no small feat on the primitive bikes and roads of the time. Harrison was popular enough with cyclists that the referee of the city's annual road race almost lost his position for explicitly endorsing Harrison in a circular, going against the officially non-partisan stance of the League of American Wheelmen and the Chicago Cycling Club, which almost expelled him and a few other members.

(Non-partisan, of course, didn't mean apolitical. The referee's endorsement of the Democrat Harrison also ran afoul of the clubs' support for the "bicycle baggage bill," a Republican effort that would have forced railroads to carry bicycles. The LAW and the Associated Cycling Clubs admitted that "were we in politics, therefore, we would urge that it would be most expedient for wheelmen to give support to the Republican party, which has given its pledge to make our bicycle baggage bill a law.")

But Harrison was a political prodigy and powerhouse, and won the first of five terms in 1897. And he delivered for the cyclists. Early in his first term, Harrison ordered that Chicago street sprinklers—who patrolled the city's dirt streets in the summer, wetting them down to eliminate dust—had to leave "a space of four feet on each side of thoroughfares next to the curb," so that cyclists didn't have to ride through slick, dangerous mud. "This unsprinkled space is intended for the especial use of bicyclists and the instruction for riders is to keep to the right." Effectively, they were the city's first bike lanes.

Later in Harrison's first term, he pushed these proto-bike lanes even further, with the first plan to pave all of downtown; a proposed compromise, where the city couldn't afford full paving, was a six-foot-wide strip on both sides, connecting downtown streets to the boulevard system and opening up the Magnificent Mile to bike traffic. Lawrence McGann, commissioner of public works and the Gabe Klein of his day, even pushed for a full bike path to reduce snarls in the city's commercial center, which the chairman of the "North Side Boulevard committee of the Associated Cycling Clubs" loved:

I have noticed in the papers of late that you intend putting in a bicycle path on Michigan avenue to Rush street. You hardly know how the North Side wheelmen will appreciate this, although they cannot use it in the morning, as wagons are backed up in Michigan avenue from 7 o'clock on. I live on the North Side and have given up riding, owing to the fact that it is almost impossible to ride down-town about 8 o'clock safely. First of all Michigan avenue is covered with water, making it unsafe to ride. I have seen many ladies slip and fall in front of wagons and trucks…. I would suggest, and you know 90 percent of the wheelmen on the North Side will appreciate, a cycle path on Rush street to Ohio, connecting Ohio street to Dearborn avenue and Pine street.

McGann responded:

In regard to the proposed improvements you can greatly assist in this matter by having the several clubs send a delegation to this department stating the routes they prefer and providing the means for paying for same. I shall be pleased to meet such a delegation at its convenience at any time you may suggest.

Paying for street improvements, then as now, was a matter of some controversy, and relations between Harrison and the cyclists were not always smooth. McGann and Harrison wanted to pave Dearborn using private money, which was occuring throughout downtown. The cyclists preferred a special assessment. "The Mayor offered to head a subscription with $100," the Tribune reported, "but the cyclists shook their heads." And Harrison, bike-friendly though he was, signed a bike-tax ordinance into law in 1897, declaring that "when the people find how much revenue the ordinance will bring in they will approve of it." (The idea had been floated two years before Harrison was elected, inspired by similar legislation in Paris, still the font of our two-wheeled infrastructure.)

The tax worked exactly how later bike taxes have, and was sold with the same logic: in exchange, riders got a bicycle tag, "fastened around the head of the wheel in such a way that it cannot me removed without breaking it." That information was held by the city clerk: "Thus when a wheel is stolen the victim of its theft can report at once to the city office. If the thief is not desirous of carrying around the owner's nameplate on the wheel he must tear off the tag and become liable to arrest for not having his wheel licensed…. In this way the tax will serve as an insurance against bicycle theft, and many cyclists are inclined to consider this as great a benefit as the proposed maintenance of the streets."

The bike tags were supposed to have the owner's name on them, but this was shot down for fear of stalkers: "The main reason for omitting the name is putting there might subject women riders to annoyance from 'mashers.'"

A war ensued, but not between cyclists and the mayor; instead, between suburban and city cyclists. The city's corporation counsel determined that the tax would apply to all bicycles, owned by Chicagoans or not, at which point suburban politicians threatened to bust Chicago cyclists for riding in their towns without a license. "Why, if Chicago undertakes to enforce that law a coalition of suburban towns is certain," Thornton supervisor Charles Applegate said. "Blue Island, Harvey, and Thornton, alone in league, could practically shut off all bicycle roads leading southward out of Chicago." Mayor Harrison clarified that no, suburbanites would just have to show proof of residence to avoid a ticket.

The bicycle tax fight went on for months, as suburbs adopted retaliatory ordinances, raising the possibility that cyclists would have to obtain licenses for every municipality they'd ever want to ride in. Supporters invoked the success of a bicycle tax in Oregon and the popularity of a pre-Portlandia's bike infrastructure. A lawsuit against the tax was filed by an ex-judge, contending among other things that "the enforcement of the ordinance would work a serious infringement on the health of many persons who are compelled to work in offices and need the exercise of bicycle riding." Shortly thereafter it was tossed out by a sitting judge, who compared the political chaos to "the early days of the German empire when every little principality had the right to stop and search travelers on the highway and collect customs duties. The point of the whole thing is that the bicycle license is a tax in disguise and it is a tax on personal liberty. It is destructive and subversive to all ideas of good government."

Not all Chicago wheelmen opposed the tax, however, and it did not chill relations between Harrison and his constituency. When Harrison battled Charles Yerkes' over control of the city's streetcars—a battle detailed by Robert Loerzel, one eerily similar to the parking-meter mess—cyclists, "my friends, the wheelmen," backed Harrison at public meetings. Harrison and McGann opened up Jackson Boulevard from Michigan Avenue to Garfield Park to cyclists, with the Union League Club and property owners along the street fronting the federal government's share to hurry the project. In 1899, Harrison addressed a crowd of 2,000 cyclists, brought together by the "Non-Partisan Cyclists' association." Harrison, the speakers said—one of whom was the almost-deposed road-race referee—"had done more for the cyclists than any other mayor." Despite the association's name, "resolutions were adopted pledging the cyclists vote of the city for Carter Harrison."

That year, Mayor Harrison proposed the greatest Critical Mass ride the city had ever seen:

The illuminated bicycle parade is to be one of the interesting features of the fall festival. Mayor Harrison will ride at the head of the procession and will be followed by 50,000 wheelmen and hudreds of brilliantly lighted automobile floats. The parade probably will form in Washington Park and move north in Michigan avenue as far as Jackson boulevard.

But those automobile would soon pass the bicycles at the head of the parade. In 1901, the American Bicycle Company—"the Bicycle Trust"—reported collapsing sales; in 1902, it went bankrupt. By then the Tribune could report that "Cycling's Death Excites Wonder," as the state membership of the League of American Wheelmen had fallen from 4,050 to 55 in four years. In 1895, the Chicago Times-Herald sponsored America's first car race. Seven years later, the oversaturated bicycle market dropped 95 percent. Mayor Harrison, the Tribune wrote, "is one of the few who have not given up the sport, and considerable of his leisure time is spent on his wheel."

What followed was a bloodbath. During the midst of the bicycle craze, the Tribune could report that "woe follows the trail of the bicycle," with 100 accidents logged by police in the course of two summer months in 1897: 10 pedestrians run down by cyclists (not too bad, considering estimates of 200,000 cyclists in Cook County), three caused by clothing catching in the bike, and one poor soul who rode into the river. But it was nothing compared to what cars would unleash on the city. In 1924, 687 people died in car crashes in Cook County. 781 died in 1925. By 1931, over 1,000 people were killed in or by cars, over four times as many as were killed last year in the county.

That decline in car-related fatalities is one of the unsung achievements of the 20th century. And now that streets have gotten safer, the bicycle is crawling back, led now as then by cities and the advocates that live in them. In their path are the same barriers, the same issues, the same models on the coasts and across the Atlantic, as big-city mayors and their bike-friendly commissioners chart the same routes through them.