Photo: E. Jason Wambsgans

Rep. Elanie Nekritz with Christin Baker, spouse of Rep. Deb Mell, after the gay marriage bill failed to come to a vote, on Friday, May 31.

In the New Yorker, Richard Socarides, a former White House special assistant and senior adviser to Bill Clinton, has a good analysis of why the gay marriage bill didn't pass in Illinois, even though it was expected to—on Friday, gay couples were invited into the speaker's gallery to watch it happen. (The only thing I'd add to it is that the legislature left itself a panic-inducing to-do list for the end of the session, including concealed carry, which passed, and pension reform, which didn't.)

Still, it's confusing; over at Capitol Fax, even the well-informed commenters there can't really figure it out. One thing in Socarides's piece jumped out at me:

Representative Greg Harris, the bill’s main sponsor, who is gay, announced at the last minute that he would not bring the legislation up for a floor vote, saying that he’d been asked by a number of his Democratic colleagues to delay it until the next session in order to give the legislators more time to discuss the bill with their constituents.

One way of reading this is that legislators need to sell their constituents on it. Another is that legislators need time to be sold on it by their constituents—that it's not something a cautious politician needs to sacrifice his career over in order to pass it. I've mentioned how this works before, and I think there's something to it.

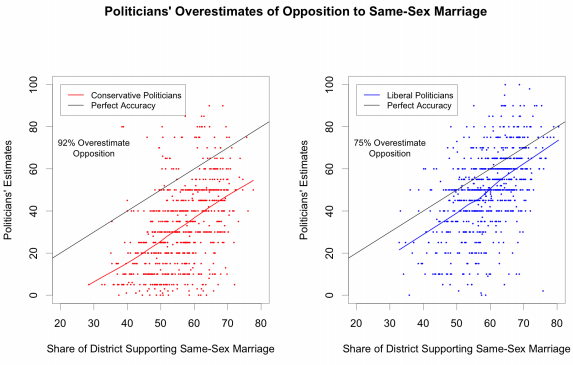

The short of it is this: legislators believe their constituents are more conservative on certain issues than they actually are, what David Brockman and Christopher Skovron call "asymmetric misperceptions." One of those subjects is gay marriage. Here's what that "asymmetric misperception" looks like.

Translated, that means both conservative and liberal politicians think gay marriage is less popular in their districts than it actually is. Conservative politicians overestimate opposition by a lot. This makes more sense than it might appear—conservatives have an active, vocal base, so it's plausible that their constituents who really make a stink about gay marriage are opposed to it. (It's not like people call up their representatives to express their passionate, deeply held ambivalence towards issues.) But liberal politicians underestimate its support as well, though not by nearly as much.

There does appear to be something of a breaking point: "in the preponderance of districts – where voters support these policies at rates of between 50% and 60% – congruent candidates have at most a 60% chance of winning while incongruent candidates have at most a 40% chance of defeat. Constituencies’ preferences do certainly express themselves in the electoral process to some extent, but in accounting for which policies their representatives will espouse they represent only a small part of the story in places where collective opinion is short of unambiguous…."

In other words, after about 60 percent approval of the issue, legislators' support of gay marriage really starts to take off, for both liberals and conservatives. And it's not quite there in Illinois: "As expected, support is strongest in Chicago, with 56 percent backing passage. A majority of 52 percent of suburban residents supports approval, but support drops to a plurality of 48 percent downstate." Greg Hinz interprets the results of that February poll as suggesting that it "may indicate that lawmakers face as much or more political risk voting 'no' as they do 'yes.'"

And that is what the numbers indicate: if people care strongly about gay marriage, they're much more likely to be for it than against it. But politicians' perception of those numbers lags behind the actual ones, raising the bar for advocates and requiring them to push past the finish line.