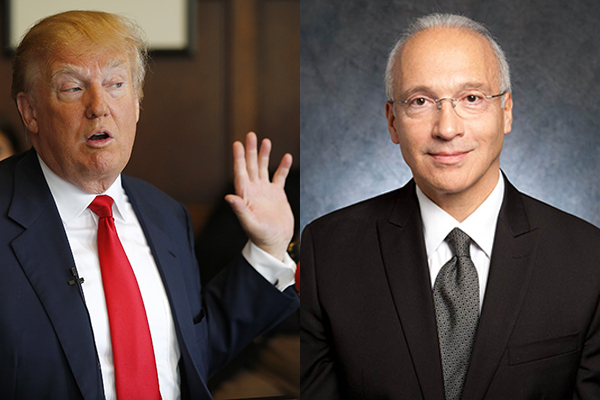

When Donald Trump targeted federal judge Gonzalo Curiel, it finally started to peel prominent Republicans away from supporting his campaign, most notably Mark Kirk. Given that the surprise presumptive nominee has built his campaign largely on a torrent of inflammatory remarks, the question isn't so much why, but why now? Jeet Heer has a theory:

By contrast, the smearing of Curiel took place in the here and now, against someone with a name, a face, and a particular history. Gonzalo Curiel was born in Indiana in 1953. His ascent to a judgeship via law school and hard work is a fulfillment of the American dream, a story of playing by the rules and rising up the social ladder. To launch a racist attack against someone like Curiel, as Trump did, was to deny national values that both Republicans and Democrats share. This wasn’t the type of structural racism that conservatives often deny exists. It was a very visible example of racism personally aimed at a successful member of American society, hence a rejection of the type of society conservatives claim they want.

Curiel was born just over the border in East Chicago, in a neighborhood called Indiana Harbor, to a steelworker father who immigrated from the Mexican state of Jalisco. His history is particular, but it is also extremely common—and historically resonant with the country's complex treatment of Mexican immigrants.

At one point, the Mexican-American neighborhood in Indiana Harbor—La Colonia del Harbor—was home to the most dense population of Mexican-Americans in the country, a population of 5,000 in a quarter-mile near the Inland Steel plant in 1930. Around that time, local companies employed an astonishing percentage of Mexican immigrants, who made up 64 percent of the Indiana Harbor Belt Line Railroad's workforce in 1928, and a quarter of Inland Steel's in 1926. The latter employed over 2,500 Mexicans.

They were there because companies needed workers. World War I shut down the European immigrant pipeline; Chicagoland's Mexican population started growing around 1916, drawn by the area's status as a rail hub. In many cases, they worked for the railroads themselves. Steel companies specifically recruited Mexican workers, recruited as strikebreakers in the wake of the nationwide 1919 steel strike. "Steel mill managers turned to Mexican replacement workers to avoid having to hire African-Americans in any significant numbers, a move some feared would provoke racial unrest similar to that of the recent race riots in other parts of Chicago," writes Michael Innis-Jiménez in Steel Barrio: The Great Mexican Migration to South Chicago, 1915-1940. (Less than a generation later, many who had been lured to the plants to lessen the risk of strikes became strikers themselves.)

By the 1930s, Indiana Harbor was growing a nascent middle class off of steel-mill wages and mutual aid societies, write Francisco Arturo Rosales and Daniel T. Simon:

From 1925 to 1930 the Obreros [a mutual aid society] published a weekly newspaper, El Amigo del Hogar, devoted to religion, literature, and news of events in Mexico. Indicative of the elite nature of the Obreros was their theater group, El Cuadro Dramático, which each year presented several plays. The director, a former professional actor from Mexico City, often staged plays that were still being performed in the Mexican capital. Further indicative of the cultural sophistication of the colonia's elite was an exhibition of original works by artist Alfaro Siquieros at a time when he was achieving international fame. More regularly, the Obreros held poetry readings, cello concerts, and similar events which could compare favorably with upper-middle-class functions in Mexico.

They also played a lot of baseball on amateur but well-organized teams, one of which was sponsored by Los Obreros, as part of a robust amateur and semi-pro Chicago-area scene.

The Great Depression wiped it out. Nine of its eleven mutual-aid societies closed. And nativist sentiments turned against the neighborhood as steel mills shed most of their capacity and unemployment rose. This was the period of "repatriation": efforts at all levels of government—with the aid of major corporations—to deport Mexican immigrants. One million were deported, some 600,000 of them American citizens.

East Chicago appealed to the government for help, led by the American Legion, which sent a letter to Secretary of Labor William Doak, requesting help "to rid this community of Mexicans…. Our theory is that those railroads who were given rights-of-way by the United States government when their railroads were built, might be willing to concede a point and run a solid train of these Mexicans to the border, or if need be, several solid trains of them to the border…. [T]he problem of railroad fare is the momentous one to us… hence our appeal to you."

Doak was in favor of deportation but offered no money to the cause, so they actually raised money for the campaign. "East Chicago had a large, highly organized, and well-funded involuntary repatriation campaign," Innis-Jiménez writes. "The American Legion coordinated this campaign in close cooperation with the township's trustee office and the Emergency Relief Association contributed financing. Working in concert, these organizations denied aid to Mexicans in East Chicago and blamed them for taking jobs away from members of the dominant community."

It worked. The Mexican population in Indiana Harbor fell by about 80 percent in the next decade.

But some remained. And there would be another World War, and with it more labor shortages. This led to the Mexican Farm Labor Agreement, otherwise known as the Bracero Program, which permitted immigrants to work in America as tightly controlled, short-term contract laborers. According to a profile by Elvia Malagon for the Times of Northwest Indiana, that's how Curiel's father ended up in East Chicago; it drew heavily from Jalisco. In total, 4.6 million Mexicans took advantage of the program, which attempted to balance agribusiness's demand for inexpensive, wage-deflating seasonal labor with the federal government's wish to control immigration.

It didn't work. Demand for bracero jobs was immense, and the bureaucracy to obtain them substantial. If anything, it encouraged more undocumented workers by creating a larger market for immigrant labor and strengthening economic and social pipelines between workers and their homes back in Mexico. When the country struggled through a postwar recession, President Eisenhower instituted the infamous "Operation Wetback." Forced removals under the program—some with deadly results—are estimated to have been between 250,000 and 1.3 million.

And that completes the circle. In one of last year's debates, Trump endorsed Eisenhower's program.

That was not enough to dissuade many establishment Republicans from endorsing the man who is likely to be the party's nominee. But the breaking point for Kirk, according to Lynn Sweet, was Trump's attacks on Curiel, and his uneasy allies in the party have lined up to distance themselves specifically from this most recent fiasco. Trump survived his embrace of the dark side of America's history with immigration, and even thrived with it, but the country has long been torn between its fear of it and the benefits that come from lifting its golden lamp. In going after a man representative of that history, Trump discovered how quickly our sentiments can turn.