The Cubs are 31-31, trapped in baseball's most desultory playoff race, one game behind the Milwaukee Brewers. The blame for the fall-off from last year's historically great, World-Series-winning team can be spread wide, but one of the biggest disappointments has been Kyle Schwarber, who's hitting .171 with a .295 on-base percentage (though the fact that his OBP is that high with such a bad batting-average speaks to his still-good batting eye).

They didn't have Schwarber last year, of course. But they sacrificed a lot to have him in the outfield this year: sitting on one of the biggest trade chips in baseball, and putting up with a substantial downgrade from last year's defense to install his bat in the lineup. About 40 percent of the way through the season, his bat has not been worth it.

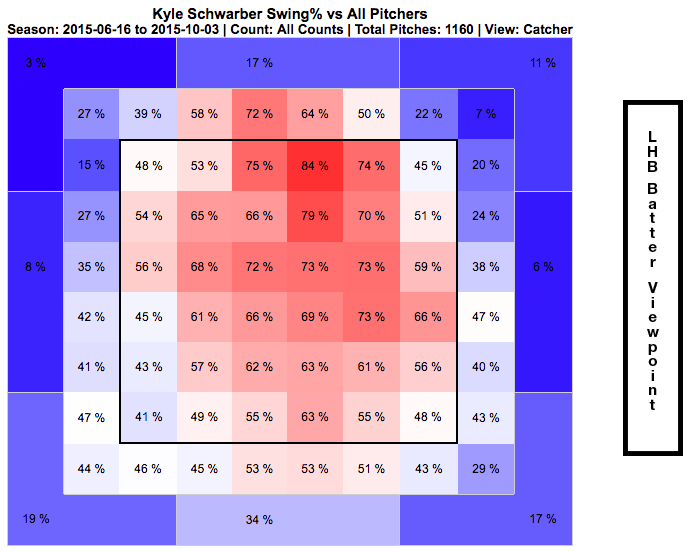

Perhaps a clue comes from a post by Fangraphs' Dave Cameron from June of last year, when Schwarber was at the heart of trade-deadline talks, casting some skepticism on his future as a hitter. To make his case, Cameron zeroed in on one aspect of his hitting: his lack of contact. "I think his contact rate presents a legitimate area that will require improvement if Schwarber is going to become the kind of hitter the Cubs are hoping he will be," Cameron wrote. "Last year, Schwarber made contact on just 67 percent of his swings, and perhaps more importantly, only 75 percent of his swings on pitches in the strike zone."

Cameron found that, of under-25 players in recent years, Schwarber had one of the lowest strike-zone contact rates, ranking 614th out of 620. That alone didn't put him in bad company: below him were George Springer (probably a star), Chris Davis (very good), Mark Reynolds (some very good seasons), Jon Singleton, and Oswaldo Arcia (both probably bad). And he wasn't far off Chris Carter and Justin Upton (both good to very good).

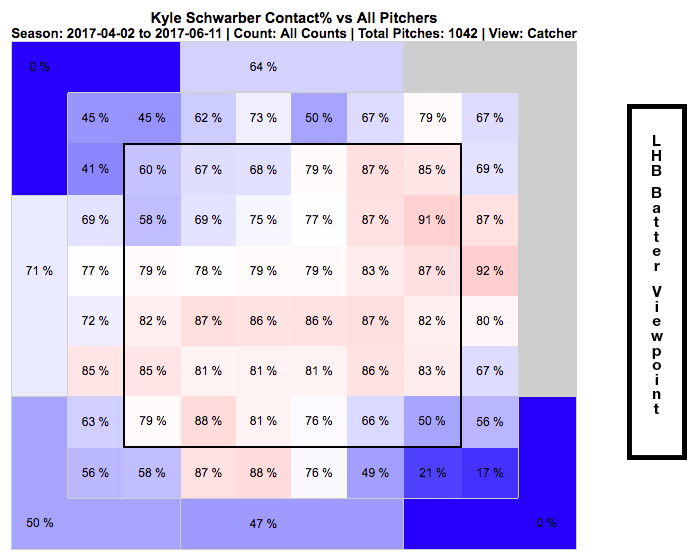

The good players in that list increased their zone contact rate, and Schwarber has done the same this year. In 2015, his zone contact rate was a low 74.8 percent; this year, it's a solid 81.4 percent. He's also making more contact on pitches outside the zone: 63.6 percent versus 57.6 percent in 2015.

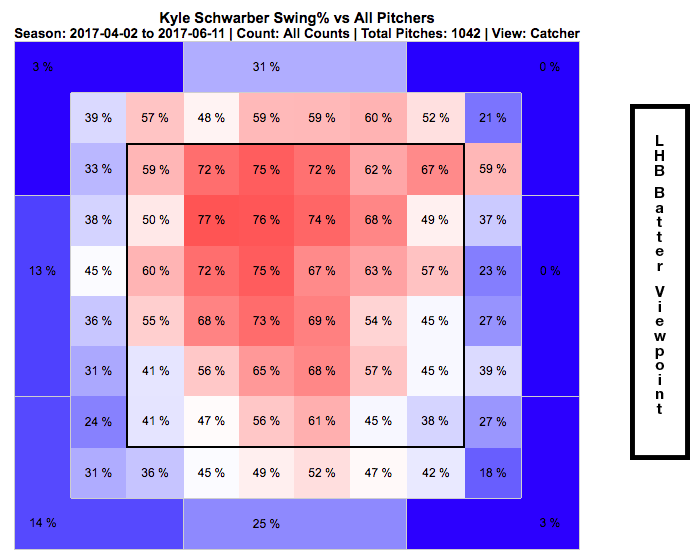

His swing rate is down a hair (from 44.6 percent to 43.1 percent), and his swinging-strike rate is way down, from 14.4 percent to 10.9 percent, though his strikeout rate is up slightly, from 28.2 percent to 30.3 percent, suggesting that he's looking at more strikes.

In all he's a more patient hitter with a wider command of the strike zone. And it's not working.

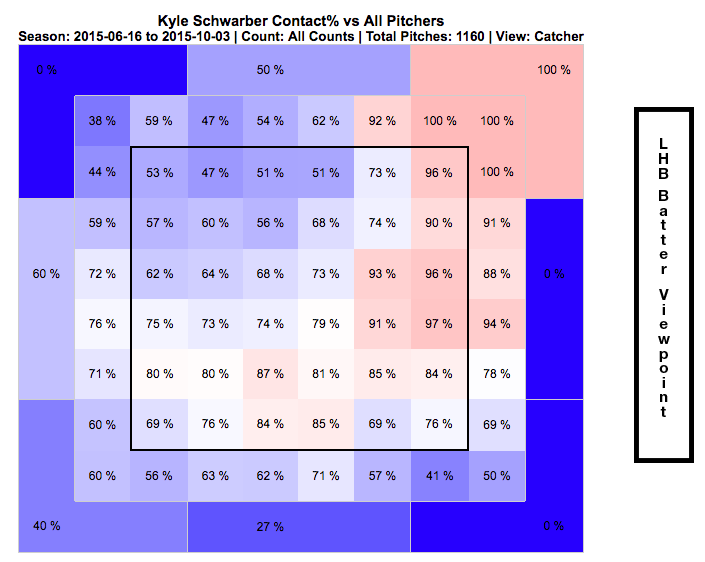

For instance, here's his contact-percentage heatmap from 2015.

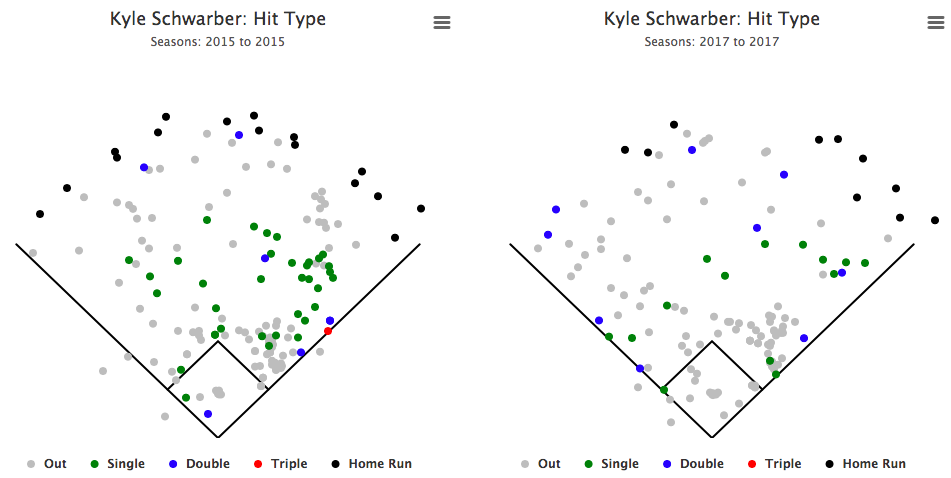

He's covering the plate a lot better, it's just that that's not necessarily a good thing. His hard-hit ball percentage is down (39.7 percent to 34.4 percent), and his soft-hit ball percentage is up (15.4 percent to 21.1 percent), while hitting more to all fields: his pull rate is down (46.8 percent to 42.2 percent) and his opposite-field percentage is up (21.2 percent to 26.6 percent).

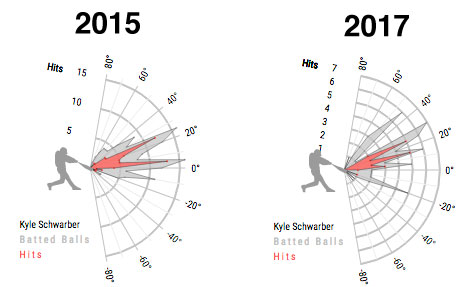

You can see that in the heatmaps too. In 2015, Schwarber was swinging at balls high and slightly inside.

In 2017, he's shifted to outside pitches a bit.

Baseball Savant gathers data on his exit velocity by zone. From 2015 to 2017, his exit velocity on pitches in and down the middle has declined, but he hasn't improved his exit velocity on pitches outside.

Furthermore, his line-drive rate has fallen to 11.8 percent, tied with Manny Machado for the lowest in baseball (another good hitter having a bad season), and his flyball rate is up as well, as his launch angle has changed quite a bit from 2015-2017 (via Baseball Savant).

Rob Arthur found that the sweet spot for hitting home runs is about 20 to 40 degrees with an exit velocity of 95+ miles per hour. Schwarber's launch angle is higher, and his average exit velocity on line drives and fly balls has dropped from 96.2 miles per hour to 92.8 miles per hour. A ball hit at 96 miles per hour at a 25-degree launch angle becomes a hit a third of the time, with 11 percent of those being home runs; a ball hit at 93 miles per hour at a 30 degree angle is a hit less than a tenth of the time. A little less velocity and a little more angle makes a big difference.

And Schwarber is making a lot more opposite-field outs.

It appears that Schwarber did, in fact, address his contact problem that Cameron noted in 2016. Unfortunately, he's not hitting the ball as hard, and he's hitting the ball up in the air. It's not a good combination, and Cameron foreshadowed it a bit: "Postseason included, Schwarber hit 21 home runs last year, but only six doubles and one triple, so 75 percent of his extra base hits were home runs. That’s why Schwarber had a .273 ISO, just a tick shy of Giancarlo Stanton‘s career .274 mark. Except no one, not even Stanton, has ever shown that they can turn that rate of well-struck balls into home runs."

This doesn't mean Schwarber is doomed. Chris Davis, one of his closest comparables, started his career with a great half season (17 home runs in 80 games), and followed that with two awful seasons and one very bad one, in which he hit worse than the average major-leaguer. In his fifth full season, he hit 33 home runs, and since then he's been one of the best power hitters in the game.

Schwarber's slump might not even be a bad thing, if it's a rough patch in developing as a more complete hitter. He's got a good team in a weak division around him, so their odds of making the playoffs are still solid, while looking toward their future as well as that of their young slugger.