Comedian (and Atlanta native) David Cross has a bit about how a particular accent associated with the rural south can actually be found in semi-rural areas all over the country. For lack of a better term, in culturally red-state areas. It's a little offensive and NSFW, but as a fellow southerner, I can attest to the phenomenon. Some of it makes sense—the first place Cross brings up is Bakersfield, California, which not only has specific historical reasons for sounding country, it has its own country-music sound. But, broadly speaking, it does seem to be real, and it is kind of weird.

Comedians are, more than almost any other profession, attuned to language, so I wasn't surprised to see that one of America's great linguists has been talking about how accent and dialect travel as much along political lines as geographical ones. And we here in Chicago are at the center of the most dramatic shift in American dialect, which has its roots in politics (via Digby).

[William] Labov points out that the residents of the Inland North have long-standing differences with their neighbors to the south, who speak what’s known as the Midland dialect. The two groups originated from distinct groups of settlers; the Inland Northerners migrated west from New England, while the Midlanders originated in Pennsylvania via the Appalachian region. Historically, the two settlement streams typically found themselves with sharply diverging political views and voting habits, with the northerners aligning much more closely with a… more liberal ideology.

This requires some unpacking. The "Inland North" is basically the Rust Belt: from northeastern Pennsylvania to Chicago, passing through the industrial centers of the Great Lakes. The "Midland dialect" region covers the area just south of that: central and Ohio west through Nebraska and Kansas, including all of downstate Illinois. Obviously, downstate is, in terms of American cultures, kind of a mutt: sort of Midwestern, sort of Southern (as is the case for Missouri, going back all the way to Mark Twain). So "Midland" it is.

Back to Chicago:

For many speakers of the northern cities, there were now no English words being pronounced with the original, now abandoned “a” sound. Since vowels evidently abhor a vacuum, this empty slot was eventually filled by the “o” sound, so that “pod” came to be pronounced like “pad” used to be.

It's part of the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, which covers the Rust Belt:

The short vowels in English, pit, pet, pat, have been standing still for a thousand years, while the long vowels did their merry chase. It's called the great vowel shift. But long about 1950, the short vowels in Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, Rochester, began to move. It's called the northern city shift.

1950 may be more when linguists began to really notice, not so much when it began. But the funny thing is that it stops just south of the big Rust Belt cities. Someone from Chicago is more likely to sound like a Buffalo or Rochester native than someone from central Illinois; if you don't believe me, take it from a Chicagoan married to a Syracuse native. It's mostly a white urban phenomenon; Labov theorizes that it originally comes from infrastructure:

Although the vowel shift is often associated with a Chicago accent, some linguists believe it actually originated in the eastern United States in the late 1800s. William Labov, a linguist and Northern Cities Vowel Shift expert at the University of Pennsylvania, believes the trend may have started during the construction of the Erie Canal, which brought thousands of immigrants from the east to the west.

During the late 1800s “you had people from all over coming to that part of the country speaking different kinds of English,” Gordon explained. “That’s the kind of environment where you expect language to shift very quickly.”

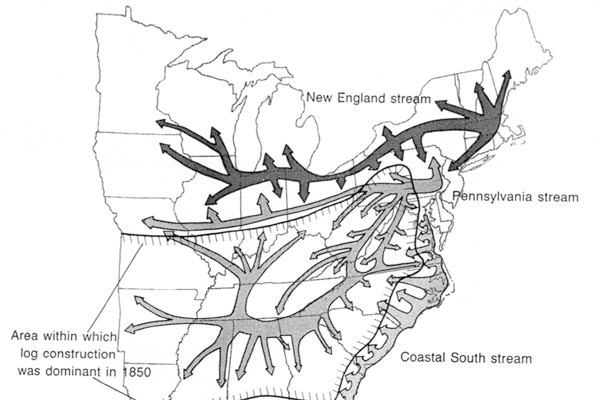

In a lengthy PowerPoint presentation, Labov shows how the Erie Canal moved the New England settlement stream west along the Great Lakes (separate settlement streams moved southwest from Pennsylvania and west from the coastal South). So, in some part, momentum carried an entirely separate linguistic culture along that narrow band.

OK, so that sets the scene for the Inland North accent and the Northern Cities Vowel Shift. Next, Labov believes that politics reinforced the shift, specifically the politics that divided all of America along north and south:

Labov explained that locals in such areas as northern Ohio and Michigan traditionally spoke precise English because they wanted to distinguish themselves from the speakers of Southern dialects in their states—a split that seems to go back to the Civil War. John Kenyon, the pronunciation editor for the second edition of Webster’s, in the thirties, came from northeastern Ohio, and he helped make Inland North the standard American dialect.

So the Erie Canal and the associated migration patterns create a difference, and then politics deepened it. And there's no reason that process can't continue:

[R]egional accents are becoming stronger and more different from each other, says William Labov, a professor of linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, although it's not entirely clear why.

One possibility, says Labov, is that these original sound differences are being exaggerated, like trains moving in opposite directions on two railroad tracks. "The other is that dialect differences have become associated with political differences, so that the Blue States/Red States division comes close to the boundary between the Northern and Midland dialects," he explains.

It's a chicken-and-egg question, but Labov has found correlation between perceived liberalism and the Inland North accent:

Do vowel-shifters sound more liberal to modern ears? Yes, at least to some extent. Labov had students in Bloomington, Indiana, listen to a vowel-shifting speaker from Detroit and a non-vowel-shifter from Indianapolis. The students rated both speakers as equal in probable intelligence, education and trustworthiness. They also didn’t think they would have different attitudes about abortion (both speakers were female). But they did think the vowel-shifting speaker was more likely to be in favor of gun control and affirmative action.

But Labov does have a causual theory for why may drive dialect and vice versa:

What causes dialects to change? Not television, Labov said. The people he calls “extreme speakers”—those who have the greatest linguistic influence on others—tend to be visible local people: “politicians, Realtors, bank clerks.” But isn’t slang a bottom-up phenomenon? “Slang is just the paint on the hood of the car,” Labov said. “Most of the important changes in American speech are not happening at the level of grammar or language—which used to be the case—but at the level of sound itself.”

It's a self-reinforcing loop. Politicians are both prominent and are usually personally connected to their city or region. Not always, but think of the stuff that non-native politicians have to deal with; even Rahm got a hard time for being from the suburbs. So people hear their (usually native) dialect a lot, and that reinforces the dialect. Politicians, wanting to appeal to the people, are more likely to lay it on thick. (As an example, three members of the Wisconsin Englishes Project at the University of Wisconsin actually charted Sarah Palin's -ing dropping in the vice presidential debate, and found that it hit 25 percent—exactly the percentage that Labov found for the speech of the lowest socioeconomic group in a classic study.) This is also where I see some explanation for David Cross's observations on dialect.

It does make me wonder, however, if the switch from the Mayors Daley and their impossibly distinctive Chicagoese to the more refined (if still very Chicago) tones of Mayor Emanuel could create a little eddy in the Northern Cities Vowel Shift, or whether years of being on the local stump will take him along for the ride.

Comments are closed.