Chuck Berman/Chicago Tribune

Chicago is a beat cop town (maybe that's why our police procedural TV shows never catch on)—after the steep rise in homicides during the 1990s, the city was the first major metropolis to adopt "community policing," with an emphasis on officers' familiarity with an area. As Jonathan Eig described the program in 2002, it's "a system built from the bottom up in which preventive problemsolving becomes more important than making arrests, a lively partnership in which police take their orders not from headquarters but from local residents."

As the homicide rate rose again last year, people looked towards Chicago's beat-cop ranks, the decline of which Ben Joravsky reported on in 2010: "In the last few weeks, Daley has proposed setting aside money in next year's budget to hire 100 new police officers. But officers tell me the department should really hire 1,000 just to keep pace with the rate of retirement. That would cost the city upwards of $60 million."

Yesterday, Garry McCarthy announced a "return to community policing," with "the same officers in the same zones every single night," putting rookie cops on the beat in some of the city's most violent neighborhoods.

But what of the not-beat cops: the detectives and their colleagues in forensics? Noah Isackson looked into Chicago's perilously low homicide-clearance rates—about 26 percent last year—for Chicago, and found the same phoenomenon as Joravsky in their ranks:

The detective division has more cases than it can handle. Teams of homicide detectives working on the South Side say they juggle as many as ten cases at a time. “You’re running from murder to murder to murder,” says one veteran homicide detective who asked not to be named. “You really want to take the time to work the case correctly, but you can’t, because as soon as you sit down to work one case, you get sent out on another.”

The 70 detectives newly minted in February will help, but their numbers don’t come close to keeping up with attrition. Not to mention the fact that the rookies have a steep learning curve after just six weeks of detective school and several months of field training, if that. “It will take at least two years for these new detectives to get good at what they do,” says Cline.

This part blew my mind: "Get this: There are now no homicide detectives stationed west of Western Avenue."

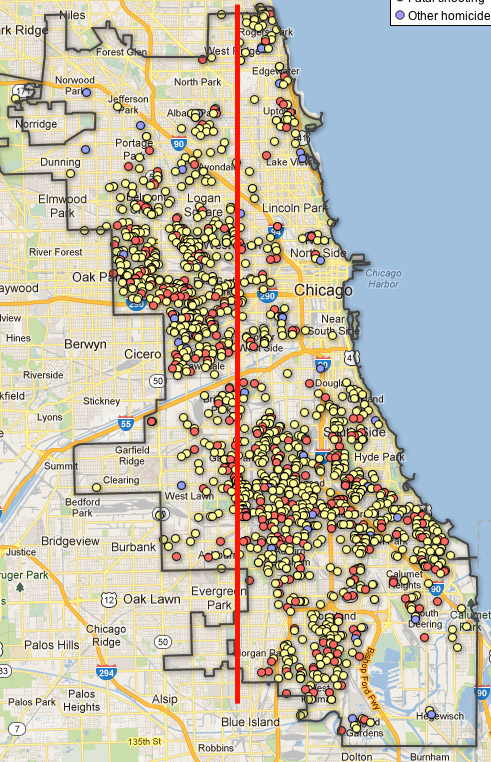

Here are the 2012 shootings and homicides, via the Sun-Times. Western Avenue is marked in red.

The particularly violent neighborhoods east of Oak Park and Berwyn—Austin, Garfield Park, Lawndale—lay between two detective bureaus on the West Side. Those were closed, and the nearest bureau is now in the Roscoe Village/Avondale/North Center area, northeast of Logan Square, about where the yellow dot on "Avondale" is.

When those were closed, cost-cutting was cited as a main reason, a savings of $10-12 million. But it wasn't the only reason given:

After facing opposition to the plan from residents who wanted to keep their neighborhood stations open, McCarthy also noted that the changes reflect the department's effort to streamline its functions and bring more officers onto the street.

Budget pressures have cut down on both beat cops and detectives, but due in part to the city's focus on beat cops, the decline in the number of detectives (who come out of the broader ranks) hasn't gotten much focus, as Isackson learned.