Anthony Souffle/Chicago Tribune

The aftermath of a three-car crash on Lake Shore Drive, March 15, 2013

A drunk driver headed the wrong way on Lake Shore Drive killed two people early Friday morning. The person charged with reckless homicide and aggravated driving under the influence is a North Chicago cop. He says he had been out "drinking to celebrate his birthday," and got behind the wheel with a blood-alcohol content of 0.184. At that point, the risk of causing a crash is over 30 percent.

Around this time last year, Chicago had gone through an odd spate of wrong-way drivers, with four in less than two months, causing four fatalities. This kind of crash is uncommon (about three percent of fatal crashes nationwide from 2004-2009) but also unusually deadly, for obvious reasons.

The Illinois Department of of Transportation (IDOT) and the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) both completed studies late last year examining why it happens. IDOT looked specifically at Illinois (PDF). The results shouldn't be surprising:

A large proportion of wrong-way drivers 35 were found to be DUI: 50% by alcohol and nearly 5% by other drugs. However, the actual percentage is higher because 50% of drivers refused or were tested with no results. Eighty percent of the drivers completing a BAC test had a level greater than 0.1%.

67 percent of the wrong-way drivers were men. Alcohol made the severity much worse:

Crashes for wrongway drivers under the influence of alcohol or drugs were more likely to result in a fatality compared to drivers under normal physical conditions. Special attention should be paid to the effect of driver BAC test results on wrong-way crash severity levels. Results indicated that the ratio of fatal crashes to total wrong-way crashes increased from 33% to 100% when the BAC increased from 0.1% to 0.4%.

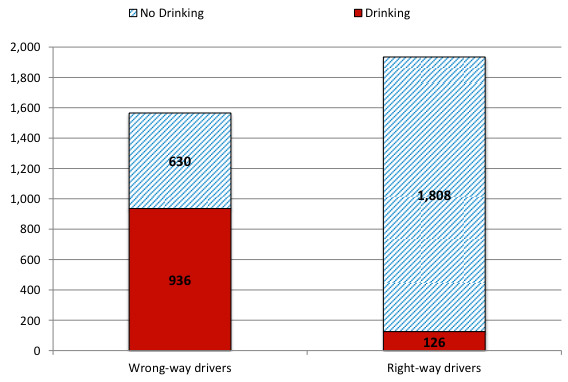

The NTSB's findings were similar (PDF). Here's their data on drivers involved in fatal wrong-way collisions from 2004-2009:

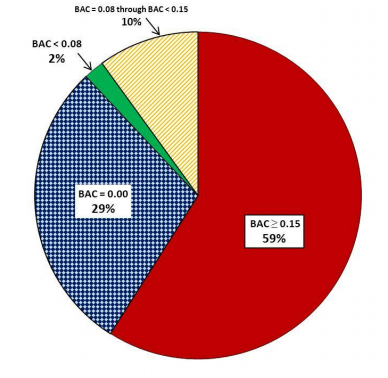

And the wrong-way drivers were likely to be very, very drunk:

A small but non-trivial percentage of those drunk drivers had a history: "9 percent of wrong-way drivers had been convicted of driving while intoxicated or impaired (DWI) within the 3 years prior to the wrong-way collision, compared to 3.2 percent for a matched control group of right-way drivers."

What can be done? Besides ending drunk driving, not much. In this case, the driver entered LSD, heading north in the southbound lanes, from LaSalle. Which means he probably turned on to Cannon, which would provide direct entry to LSD:

A soft right turn at that intersection takes you onto LSD. A left would go north into the southbound lanes. Here's what it looked like in June 2011:

The LaSalle and LSD intersection isn't in the IDOT report, but the LSD/Belmont intersection is—it was the entrance for four wrong-way drivers from 2004-2009.

Among other things, the report noted some basic maintenance that could help. (The report's recommendations appear as text within arrows in the images below:

The best way to prevent wrong-way crashes is preventing drunk driving. That's not something traffic engineers can do, though. They just have to work with the world as it is, and attempt to account for the prevalence of drunk driving in Chicago.

All they can do is try to make the roads as foolproof as possible, and hope that the signs are clear enough—even to people irresponsible enough to get behind the wheel drunk.