One of the terms you might have come across since the Great Recession, if not before, is the "bond vigilante": investors, or people presuming to speak for them, issuing dire warnings about the country's finances, its debt, and how that is terrifying the market. Their significance has been widely debated—whether or not they have a point, what it is they actually want from government, how pessimistic we should be, and so forth.

If you want real pessimism about the future, you don't need to ask an investor—just look at the more prosaic microeconomic level of the consumer. The Chicago Fed recently looked at metrics from the Michigan Surveys of Consumers, and found Americans' confidence at all-time lows: "Consumers’ expected income growth declined significantly during the Great Recession. It was the most severe drop in income expectations ever observed in these data, and expectations have not yet fully recovered to pre-recession levels." This lack of confidence is at a level unseen in my lifetime, and at a level unmatched in my parents' generation as well.

And optimism is particularly low among those who should have the most reason to be optimistic.

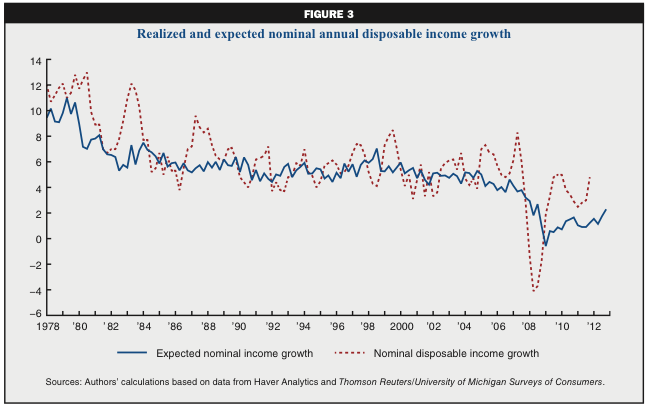

You can see the shock wave of the recession in this chart of realized versus expected income growth. Over the past few decades, Americans have been pretty conservative about their expectations, which have followed the decline in nominal growth while tempering out its shocks. Then the Great Recession hit, and it was much, much worse than anyone thought it would be.

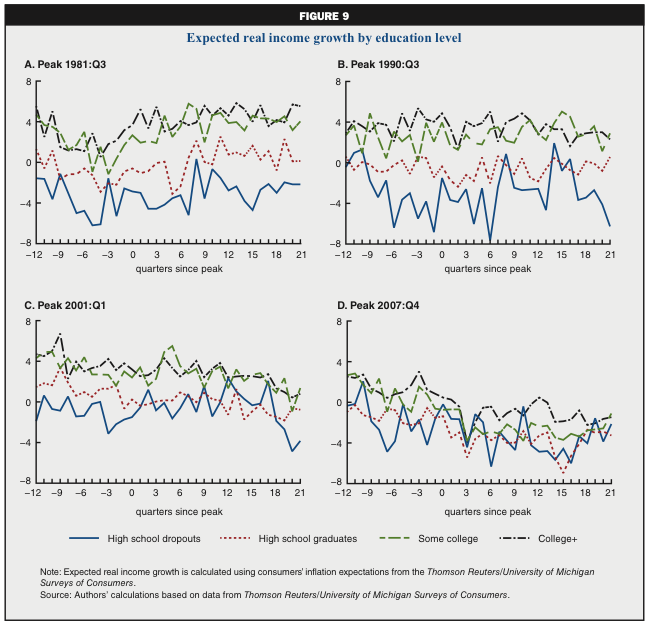

What's interesting about this pessimism is that it's really fallen on college graduates. In prior recessions there was a considerable spread among people with different education levels—as you'd expect, college grads were considerably more confident that their incomes would start to grow again.

This time around, everyone has the same low expectations for their income.

It's not irrational. That flattening of expected real income growth, like a layer cake being squished, mirrors broad economic changes:

“The Great Recession has quantitatively but not qualitatively changed the trend toward employment polarization” in the United States, wrote the MIT economist David Autor in a 2010 white paper. Job losses have been “far more severe in middle-skilled white- and blue-collar jobs than in either high-skill, white-collar jobs or in low-skill service occupations.” Indeed, from 2007 through 2009, total employment in professional, managerial, and highly skilled technical positions was essentially unchanged. Jobs in low-skill service occupations such as food preparation, personal care, and house cleaning were also fairly stable. Overwhelmingly, the recession has destroyed the jobs in between. Almost one of every 12 white-collar jobs in sales, administrative support, and nonmanagerial office work vanished in the first two years of the recession; one of every six blue-collar jobs in production, craft, repair, and machine operation did the same.

It actually sort of makes sense that college grads would (broadly) be as pessimistic as high-school dropouts, if low-skill jobs are more stable and white-collar jobs are collapsing. Seeing that, college grads are (moving back to the Chicago Fed report) pulling back on spending:

Although the college educated still expect faster income growth than the less educated, the differences are less stark than in the past. This is consistent with Petev, Pistaferri, and Eksten’s (2010) findings. First, they find that increased government transfers supported income among the poorest-income households during the Great Recession. Second, using the Consumer Expenditure Survey, they find that survey respondents in the top decile of the wealth distribution (who are mostly college educated) are the ones who decreased spending the most during the Great Recession (which is also consistent with the findings of Meyer and Sullivan, 2013).

And prediction is prologue: "expected income growth is a strong predictor of actual future income and consumption growth. For this reason, forecasts of near-term consumption and income growth using these data suggest sluggish income and consumption growth over the next year."

Photograph: meddygarnet (CC by 2.0)