Terrence Anonio James/Chicago Tribune

Rahm Emanuel, Michael Bloomberg, Richard Daley

No, I know. But thanks to the magic of statistics, we can pretend.

Big cities actually do sometimes elect Republican mayors. Sometimes they might not seem all that Republican, like the soda-banning, gun-hating, Chicago-progressive-supporting Michael Bloomberg. And the differences aren't that vast. As Elizabeth Gerber and Daniel Hopkins write in their study (PDF) of mayoral partisanship, "the old adage that there is no Republican or Democratic way to collect trash, attributed to New York’s Mayor LaGuardia, appears quite compatible with the reigning theories of urban politics."

There's a big reason that the difference between Republican and Democratic mayors is not big, and it's important: mayors are constrained on what they can do with their money:

For the cities in our data set, state and federal intergovernmental revenues account for 81% of their total spending on housing, 33% of their total spending on roads, and 27% of their total spending on health and hospitals. But the comparable shares for policing and fire are so small that they are not reported. And even if every dollar of miscellaneous intergovernmental revenue went to fire and policing, the comparable share would be no larger than 21%. In all likelihood, the true figure is considerably smaller.

In other words, the big chunk of city budgets is public safety, and that's where mayors have the most control. It is true that particularly powerful mayors have had more sway in the past—Richard J. Daley's control over federal poverty spending was legendary, but federal aid to cities has declined. So cops and firefighters are the big game in town (especially cops), and the city's budget reflects that.

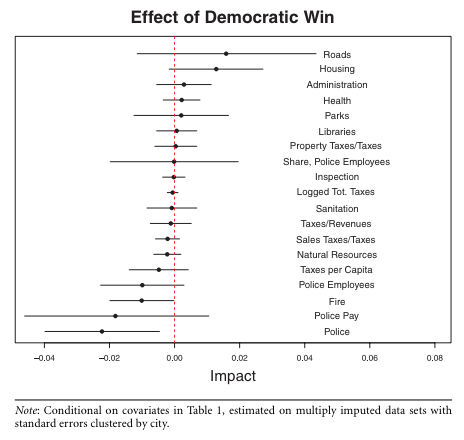

It's also where the difference between Republican and Democratic mayors lies:

Translation:

When Democrats narrowly win the mayor’s chair, spending on policies such as policing—a policy area defined by low levels of overlapping authority—commonly declines relative to total spending. There might not be a Republican way to collect the trash, but there is a Republican way to spend on policing and fire protection.

[snip]

[N]arrow Republican victories are associated with a substantial and statistically significant increase in the share of city budgets going to these functions. These results are strongest in cities where parties play a formal role in nominating candidates. Under these conditions, the relationship between what decision makers want and the outcomes they produce is much clearer.

One big caveat is that this finding is for races with narrow wins, but in a big city election in which a Republican has a shot, you'd expect a narrow victory at best.

The other is that spending is a narrow way of looking at mayoral power. A strong mayor can have a lot of sway in the state legislature (or even the federal government), which might not show up in the city's share of spending but does end up on the books. And the ongoing battles over CPS show that, even if spending doesn't change all that much, a mayor's philosophy and ideology can hold considerable power that's not reflected in the raw numbers.

But the raw numbers are still important, and suggest the circumstances in which a Republicans can win in a big city—and what the results are when they do.