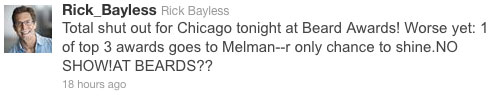

Huh (via Eater Chicago):

Curiously, the reason Melman gave the Tribune for not being there was that he hadn’t heard about the Beard Awards.

I don’t have a dog in this fight/imbroglio/tiff/whatever it is—call me when Taqueria Traspasada #2 is nominated for "Best Taco Stand Within Spitting Distance of a Public Library"—but it does give me an excuse to remind people of perhaps my favorite essay about the recent history of Chicago food: "Let Us Now Praise R.J. Grunts" (great title) by Elizabeth Tamny.

In the aforementioned Trib article, Christopher Borelli writes:

Maybe it was the name…. How else do you account for its Chicago founder, Rich Melman, being nominated six consecutive times for the James Beard Foundation’s outstanding restaurateur of the year award and never winning? Puns and prestige don’t mix.

You want puns? Melman’s empire once opened a restaurant with the worst pun name of all time: "Jonathan Livingston Seafood." Democratically, this doesn’t dissuade Tamny:

[T]he rosters at places like Alinea, Avenues, and Moto owe as much to Melman as they do to Trotter: Lettuce has provided a means of keeping culinary talent in town–with the company’s general professional opportunities, certainly, but also with corporate jobs that provide income during the inevitable transition periods in chefs’ careers. Melman has been able to offer midlevel employment solutions in the all-or-nothing restaurant world to talented chefs who need a break from its harsh demands or aren’t quite ready to dive into launching their own place. Mary Ellen Diaz, for instance, worked as a corporate Lettuce chef after burning out at North Pond Cafe; Gabriel Viti served two years as a Lettuce chef before stepping into the head chef position at Carlos’ and eventually opening his own restaurant.

Even more important has been Melman’s influence on the average Chicago restaurant-goer. The newly knowledgeable and adventurous diner is, according to Charlie Trotter, the biggest difference between being a restaurateur now and when he first began. "People were intimidated back then," he told me last year. "Now . . . they’re more savvy and understand things, which is great for all of us who are trying to cook and push the envelope."

It’s a great essay, not just because of what it says about Chicago dining, but also about the evolution of consumption, which is why I keep referring back to it.

Related: An 2000 essay on LYE’s aggressive, detailed self-policing.