Chicago-Michigan football game, 1903

In November 1905, Vernon Wise, the 17-year-old son of a hardware wholesaler, lined up at right end for the Oak Park junior varsity football team. Slight of build and fragile, Wise wasn't much of a player, even on a second team whose players averaged 138 pounds, but he was tenacious, "nervy," and popular, enough that he was named captain of the team—which he declined, in favor of his friend, the team fullback.

A handful of fans, mostly younger students, were watching as Wise threw himself at a Hyde Park opponent, who collapsed on top of him, followed by a "struggling mass" of players. Wise was knocked unconscious, and taken to a doctor; his replacement was kicked in the head on the next play, the fourth casualty of the game, after which it was called. Wise briefly regained consciousness, during which he told his mother that he would give up the game, "even if I don't get the [letter] sweater." Two hours after the hit, he died of a broken back.

Wise was hardly alone in his death on the football field. The November prior, a Chicago man whose 16-year-old son died of peritonitis after a football game pushed state legislation to get the sport banned, joining with an Indiana state senator and a Wisconsin man (whose sons had died the month before) to eliminate the sport in the tri-state area, along with Michigan. But for some reason, Wise's death gripped the local press, in part because the Oak Park and Cook County school boards took up the proposition to replace the popular sport with lacrosse and soccer, respectively. The Alton school board banned the sport after its high school's right tackle died in an October game; "Capt. E.D. Enos of the Alton team, whose collar bone was broken in the same game, was at the funeral swathed in bandages."

The rash of local injuries came just a couple weeks before the president of the United States, Teddy Roosevelt, telegraphed Harvard president Charles Eliot asking him to address the year's record of 19 deaths—"more than double that of the yearly average for the last five years, the total for that period being forty-five"—for fear the sport's bloody reputation would get it banned outright instead of changed to protect the players. In particular, Roosevelt pushed the "open game," whose players, he said, "escaped with less than their usual quota of accidents." It was meant to save the game from the vicious scrums seen in the Edison film above, which look quaint in black-and-white but caused the debilitating or fatal injuries that felled players like Wise.

From this the modern game of football was born: the forward pass, the ten-yard first down, the lengthening of the line of scrimage, a new emphasis on penalties and improving the quality of refereeing to prevent the dangerous "mucker" play on the lines, and the creation of the NCAA's predecessor. The movement to ban football, which was quite strong at the time, faded. Fatalities plunged, and the crisis settled down.

Was it a crisis? The sport was dangerous, but it was also a sign of the Progressive era:

What does this tell us about the 1905 crisis? Simply this: The varying agendas may be attributed to many factors, including the reform efforts common to the Progressive Era. In the early 1900s the country experienced one of its most intense periods of self-criticism and political unrest. Earnest reformers attempted to eliminate corruption and inefficiency, reintroduce democratic practices, and improve the standards of safety. Thus in 1906, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act, the medical and gastronomical version of the new football rules. As in politics, college athletics had its version of muck-raking journalists, who like journalists Ida Tarbell and Lincoln Steffens burrowed into the unethical activities of win-at-all-cost coaches and alumni.

Indeed, injuries would rise again, precipitating another crisis in 1909-1910 that's not nearly as famous.

One problem was a lack of good data. Not until 1931 were statistics regularly kept on football fatalities. Over the years, those numbers would show a pattern of deaths that would return to the numbers that nearly ended football in America before it began.

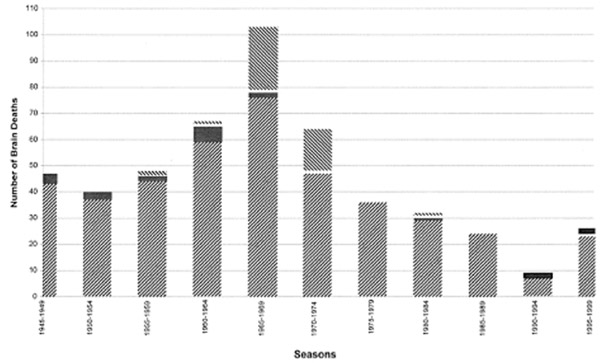

That's the history of football-related brain deaths in numbers, in five-year increments from 1945-1999. Between 1965 and 1969, more than 100 players at all levels died of brain injuries, an average of about 20 per year—about the same number as died in 1905, but from brain injuries alone. The mounting number of head injuries, and the pioneering work of University of Michigan neuroscientist Richard Schneider during the 1960s, led to significant equipment and rule changes that altered the sport and made it profoundly safer, at least in the short run:

Schneider established a laboratory model at the University of Michigan to study head and neck injuries, and these experiments ultimately led to the development of the protective helmets used today. In addition, he used game and practice films to study the mechanisms causing these injuries, and his findings led to major rules changes banning so-called spearing and butt-blocking. The result was a dramatic reduction in the incidence of athletics-related “serious” head and spinal cord injury, as documented in the National Football Head and Neck Injury Register and the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research data statistics.

The change was extraordinary; between rule changes and the 1973 creation of NOCSAE, the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment, head-injury fatalities in high school football declined by three-quarters.

But the new equipment, meant to protect from sudden death, forces a tradeoff with the death of a thousand blows that claimed Dave Duerson and possibly Junior Seau, as Jonah Lehrer writes:

But here's the bad news: These old regulations provide scant protection against concussions. While a hard plastic helmet lined with cushioning can protect the skull from fracturing, a concussion occurs on the inside of the head, when the brain quickly decelerates and impacts bone. This means that helmet designers face an inevitable tradeoff: If the head isn't shielded from the strongest physical impacts — and this is best done with soft, pliable materials — then it can break and bleed. But the very act of protecting players from those severe collisions means that the head will bounce around the cushioned helmet, thus allowing the brain to move within its bony cage. The worst impact will be internal.

Which is why I caution against this sort of conclusion:

They could eliminate substitutions and go back to the old-style game with players playing both offense and defense, and make other tweaks, like allowing defensive backs to use their hands up and down the field. But then the sport would be back in high tops, clunky, looking like 1958, and it wouldn't be as spectacular.

What the NFL owners wanted was high-impact spectacular play and touchdowns to sell tickets, and they got what they wanted, and bought it with the bodies and brains of their players.

At all levels, those involved with football saw an increasing problem, and worked with the tools of science and engineering to address it. And by the measures of brain deaths, quadrapelgia, and cervical injuries, they were wildly successful. But similar advances were also leading to bigger, stronger, faster players at all levels. Meanwhile, the science that was so good on severe head injuries was comparatively primitive on concussions, which only became a subject of intensive study in sports medicine in the 1980s.

And we still know very little about them (again, Lehrer):

In recent years, it's become clear that the severity of a concussion is only indirectly related to the physical force of the impact. Sometimes, players walk away from savage hits. And sometimes they are felled by incidental contact. While data compiled from the Head Impact Telemetry System, or HITS, captures the extreme physical forces at work during a football game — it's not uncommon for a player to sustain hits equivalent to the impact of a 25 mph car crash — there is no clear threshold for injury. The mind remains a black box; nobody really understands why it breaks.

Bone-shaking hits—"high impact spectacular play"—often get blamed for the rash of concussions and the long-term mental problems they cause. But research at Purdue suggests that a culprit is the totality of hits a player sustains over the course of a season or a career:

"The most important implication of the new findings is the suggestion that a concussion is not just the result of a single blow, but it's really the totality of blows that took place over the season," said Eric Nauman, an associate professor of mechanical engineering and an expert in central nervous system and musculoskeletal trauma. "The one hit that brought on the concussion is arguably the straw that broke the camel's back."

[snip]

A common assumption in sports medicine is that certain people are innately more susceptible to head injury. However, the new findings suggest the number of hits received during the course of a season is the most important factor, Talavage said.

"Over the two seasons we had six concussed players, but 17 of the players showed brain changes even though they did not have concussions," Talavage said. "There is good correlation with the number of hits players received, but we need more subjects."

The Purdue researchers are expanding their research into soccer, something to look forward to in light of a 2011 study that linked heading the ball (which creates an impact around 20 Gs, the low end of impacts they measured on football players) with brain damage much like that found in football players.

If anything, this is a scarier possibility: that the brain damage linked to recent NFL tragedies can't merely be addressed by cracking down even more severely on barely legal hits or high-speed collisions, but that it's an ingrained part of the many small, inevitable helmet-to-helmet or helmet-to-knee collisions that occur during the game, and that it will be difficult or impossible to improve the equipment without sacrificing the improvements that have prevented so much severe brain injury.

During the 1960s, football became a much more deadly sport on the field. We've only recently begun to understand how the violence on the field becomes deadly off it. If anything's going to change, it will likely be at the collegiate or professional level, where the money and research exists to improve the equipment and the rules. But if we're to get rid of it altogether, don't look to the pros—look to high school and college, where voters and parents have some say, just as they did back in 1905.

Comments are closed.