The outbreak of violence this warm Memorial Day weekend—10 fatal shootings, 40 wounded—has brought another round of media coverage about the city's increased homicide rate in 2012, and with it some perplexing statistics. For instance:

Through Sunday, there have been at least 200 homicides compared to 134 during the same period in 2011, a 49.25 increase, according to unofficial police data.

Shootings are up nearly 14 percent over the last year through Sunday: 851 compared to 747 in 2011, according to the data.

Shootings are up slightly, homicides are way up. It's a reminder that it's not a one-to-one relationship. The difference between a shooting and a homicide can be a matter of inches; one of the Friday shootings was a graze wound to the head which left the victim in good condition, but a literal hair's breadth from being another homicide. Sometimes more shootings turn out to be lethal than others. Curiously enough, despite the intensive research on murder and homicide rates in American cities, there's virtually no research on the subject.

The sole paper I've found on the subject comes from two Columbia University economists, Brendan O'Flaherty and Rajiv Sethi, and it looks at murders in nearby Newark. Between 2000 and 2007, Newark saw a near-doubling in the number of murders, going against well-known national trends. But it didn't see a comparable increase in the number of shootings:

Gun homicides increased by more than 70 log points between 2000 and 2007, but shootings actually decreased over this period. The rise in homicides cannot therefore be attributed simply to more shootings. A higher proportion of shootings had intent to hit someone, and a higher proportion did hit someone, but the major story is that the probability of a murder conditional on a hit rose: 56% of the log rise in gun homicides is due to the higher conditional probability of death conditional on being hit by a gunshot. Murders rose mainly because shootings became more deadly, especially shootings where someone was wounded.

Given the data, the authors did as much as they could to separate shootings from motive, and motive from accuracy. Intentional shootings increased, and accuracy increased, but even that wasn't enough to explain the rise in gunshot deaths. Quite simply, the people who were hit died more frequently.

This raises a number of unsettling questions:

Possible answers are: (i) potential murderers acquired better weapons with the capacity to fire more frequently, so a higher proportion of gross gun discharge incidents involved multiple shots, (ii) potential murderers acquired higher caliber weapons that were more likely to kill when they did not make direct hits, (iii) potential murderers acquired more skills, (iv) potential murderers exerted more effort in trying to kill their victims (for instance by standing closer to the victim or driving by more slowly or firing more shots), and (v) emergency medical care became less effective.

They were able, roughly speaking, to evaluate some of those answers, using police reports and reports from the state medical examiner.

They indicate that gunshot homicides increased because of better marksmanship and greater effort, because of higher caliber weapons, because a larger proportion of gross gun discharge incidents involved multiple shots (either because of the presence of semi-automatic weapons or greater willingness of perpetrators to keep firing), and because the number of gross gun discharge incidents increased. Our models are too crude for us to have much confidence in the exact attribution, but each of these factors seems to have made a significant difference. Shootings became more deadly in all dimensions.

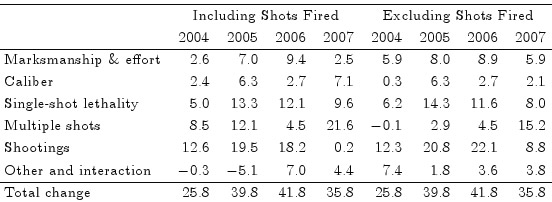

Living in Chicago, I hear gunfire occasionally. Usually it doesn't bother me all that much. It does, however, when a shooting, from the sound alone, sounds like an explicit intent to kill. Using crude but clever measurements, the two economists attempted to break down why murders increased based on five factors: the number of shootings, multiple-shot discharges, single-shot lethality, caliber, and "marksmanship and effort" ("the difference between the number of murders attributed to single-shot lethality and the number attributed to caliber"). From these metrics, they estimated the number of additional homicides attributable to each category, and found that the sum came close to the total:

The cause for the increase in murders changed. Caliber played a small role in 2004, and a large one in 2007. Multiple shots "caused" more than half the increase in murders in 2007, but a mere ten percent the year before—a year that single-shot lethality was a substantial factor.

The authors offer a handful of strategies for reducing murder rates, their strongest suggestions being increasing the number of police (an ongoing issue in Chicago) and emphasizing strategies for prisoner re-entry: "The key is finding things that 30-year-old former prisoners like to do after work, and helping them to do these things in an atmosphere without guns and where disputes are settled amicably, or with fists."

But it's perhaps most useful as a reminder that homicide statistics are inevitably simplified. Under the bottom-line statistics, there's an immense amount of complexity.

Related: Yes, heat—but not too much heat—might be a factor.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune