Last week I interviewed Chrissy Mancini Nichols and Peter Skosey of the Metropolitan Planning Council about their new study of Chicago's parking meters: what the deal looks like now, and how it could be better. I didn't think, having followed the story since its inception—I was at the Reader when Mick Dumke and Ben Joravsky really dug into it—that they would say anything that really surprised me.

I should not have assumed that.

"At the time, prior to the 2013 renegotiation, the city did not have access to parking usage data. [Chicago Parking Meters] calculated whatever the true-up was supposed to be that year," Nichols says. "The city just said, okay, here's your check. They didn't know what was all going in the calculation. In 2013, that changed. The city now does the calculation, and they say, this is what we believe the true-up is. And then CPM certifies it."

The true-up, to make a complex calculation simple, is this: a certain amount of revenue is supposed to come in from the parking meters. If the city does anything to decrease that revenue, which could be anything from holding a parade that takes some meters out of commission, or moves meters, or changes the time limit at the meters, it has to "true-up" the revenues to CPM, so that CPM gets the revenues it expected when it leased the meters.

This, as you can imagine, is a very complicated calculation. And in that calculation, data is leverage. For instance: When the two-hour time limit was set, some businesses reasonably complained, like theaters, since two hours is generally not quite enough to see a movie or play.

"On 10,000 meters, the city increased the time of stay from two to three hours. It was right during the downturn. The rates [contractually] had to go up every year. They extended the time from two to three hours, and at the same time they raised the rates. The utility at those meters all went down; people parked less," Nichols says. "Under the concession, if the city touches a meter, regardless of what they do, if that meter decreases utility, than the city's on the hook. CPM said, you just touched 10,000 meters, utility went down, it's your fault. For 73 years, you are required to make that utility up for us. It was a cost of about $25 million [annually]."

The city quite reasonably claimed that the substantial, contractually obligated parking rate increase, not the extension of the time limit, caused people to park less. Which is the kind of argument you can make when you have the data to make it. Among many other things, the 2013 renegotiation not only gave the city the data, it allowed the city to make its own true-up calculations and present them to CPM.

That's why the Metropolitan Planning Council argues that the deal, which came in for criticism both strong and mild, will in fact save the city a substantial amount of money over the deal's long timeframe.

But they also argue that the city could take further advantage of the deal. The flip-side to the true-up is this: if revenues exceed that break-even point, the city could bring in money from parking, rather than falling below the break-even point and having to actually pay CPM.

There are ways to do this that won't bother anyone. Take this mind-bending statistic on disabled-placard fraud from the report (emphasis mine):

Beyond being illegal, abuse of disabled parking has major financial implications: In the first four years of the concession, people who fraudulently used disabled placards to park for free in metered spaces cost City taxpayers $73 million. Placards were so widely abused that in one year, a truly astonishing number—more than 90 percent—of people parking on Loop streets did so with a disabled placard, compared with the six percent allowed. Monthly sting operations by police have found that one in five people parking with disabled placards are doing so illegally.

If the city had kept the meters, that would merely be lost revenue. But thanks to the true-up, remember, lost revenue has to be paid back to CPM. Recently the state changed the law, greatly narrowing the kind of handicaps that permit free parking at metered spaces, and the savings to the city was one of the headlines.

So the city's cracking down; Nichols and Skosey say that it's working, but also warn that it's difficult to enforce, and that scofflaws could find creative ways around the new law. It'll continue to be a game of cat and mouse.

More controversial would be a means of not just preventing loss, but increasing revenues. That's is, obviously, more meters, and more variation in meter pricing. Which people won't like the sound of. But the case that Nichols and Skosey try to make, one that's at the vanguard of urban planning, is that both are good for residents, businesses, and the city.

The good news is that it could mean cheaper parking, at least at some times. "The meters are not occupied in Bucktown during the weekday. But they're still shopping at the stores, and they're still going to the coffee shops," Skosey says. "Perhaps at the right price, they drive there, and we could generate more business for those stores. I'm sure there are people who say, 'it'll cost me two dollars to park, and I'm only getting a two-dollar cup of coffee. So I won't go there.' Whereas if you have a more reasonable rate, you could generate more business for those stores. Fifty cents is better than no cents. Parking meters are a tool for managing demand; that's what they were invented for. When they're used as such, that's when they have their greatest impact."

But sometimes that tool means getting people out of parking spots. In 2014, MPC (update: in collaboration with the Chicago Metropolitan Planning Agency) published an extensive study of parking in Wicker Park/Bucktown. What they found is perhaps surprising. First, there's a lot more free parking than metered parking: 8,553 free spaces, compared to 1,025 metered spaces (and 1,775 permit spaces).

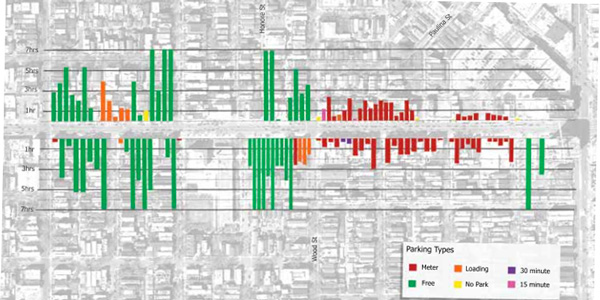

And people sit in those free spaces. Here's what Division Street between Ashland and Damen looked like on May 24, 2013. The bars represent the average time cars spent parked in individual spaces.

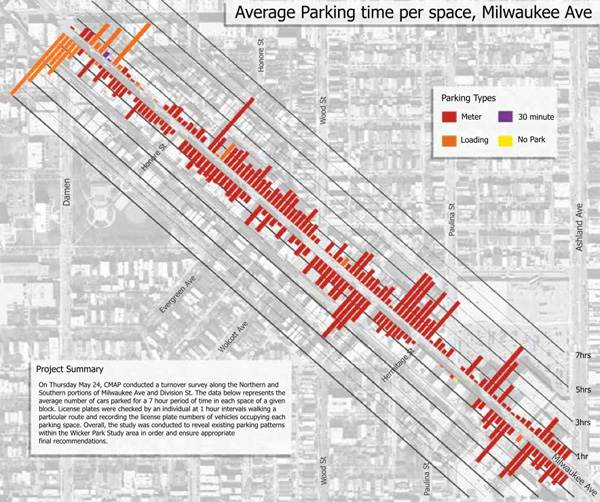

Unsurprisingly, there's a lot more turnover in metered spaces. Which, if you're a business owner, is what you want: a reasonable promise of open spaces for shoppers. Compare that to the heavily metered section of Milwaukee running south from Milwaukee/Damen/North, a popular shopping and dining corridor.

Their goal is an 85 percent parking occupancy level: active, but with available parking. San Francisco recently tried a federally funded pilot program aiming for 60-80 percent occupancy using dynamic pricing, and their results, released in 2014, were extremely encouraging: time spent looking for parking fell by nearly half; total vehicle distance traveled declined by almost a third; the average hourly rate fell very slightly, using the kind of pricing suggested by Skosey: "many of San Francisco's pilot-area blocks sat relatively empty when parking cost a flat rate ($2.00, $3.00, or $3.50 per hour, depending on location) because those blocks were not desirable. Now, with parking as low as $0.25 per hour in some locations (the minimum price allowed under the program), demand is distributed more evenly across space."

How'd they pull it off? As Stephen Crim at Streetsblog suggests above, the city marketed it well, selling the benefits that were eventually generated by the pilot.

And then there's this:

Between the evaluation report, the program's technical documentation, an upcoming evaluation from [the Federal Highway Administration], and the downloadable data sets that program managers routinely update, there is a lot of quantitative data that researchers, activists, policy-makers and citizens can study in great detail.

The city has a lot of options going forward for modernizing its approach to parking, and possibly turning its true-up deficit into a revenue stream. At the very least, it now has the data to build on.