On May 31 the Illinois legislature will wrap its spring session, signaling the last chance our state has to pass a budget for the upcoming financial year, which begins July 1. This would not be a news item in itself if Illinois hadn't already suffered two years without a coherent spending plan; worse, it seems poised to go into a third.

How did we get to this point, and why should you care? This week, Chicago is digging into these questions and letting you know what you can do about it.

What is the state budget, and why do we need it anyway?

One of the reasons we elect legislators is to oversee the money that comes into the state and the money spent on state services: health care, education, and correctional services, among many others. The budget is the annual agreement that lawmakers put together to pay for these services. How much they can spend on services depends on how much revenue they take in through taxes and other means. If they don’t have enough to fully cover services, then they have to borrow money, raise taxes, cut services, or some combination of those three.

Without a budget, Illinois is still collecting taxes and spending money. The difference is, nobody is taking responsibility for it. When a normal budget is passed, lawmakers must make decisions based on the state's financial position, and taxpayers can see how and why money is being spent—and hold them accountable for it. Right now, spending is instead largely dictated by court decisions after various groups sued the state for payment.

If it's so important, why haven't we had one for two years?

Illinois has $130 billion in unfunded pension obligations and a $9.6 billion hole in the general funds budget. Some of these payments need to be addressed in the annual state budget but, since July 2015, Illinois lawmakers haven’t been able to agree on exactly where and how to face these financial problems. That means state funding for important services like schools, hospitals, and criminal justice has been held up for the past two years.

So why can't lawmakers come to an agreement?

The state budget is not just a cut-and-dry document: It’s also how the state lays out its priorities for what needs to be funded, what can be cut, and by how much.

When Governor Bruce Rauner took office in 2015, he said that voters gave him a mandate to “shake up Springfield” through his “Turnaround Agenda,” which included pension reform, changes to union rules, cuts to Medicaid, and a range of tax cuts. At the same time, Illinois was struggling with a historically huge pension obligation due to decades of putting off payments or borrowing.

Both Rauner’s agenda and any comprehensive pension solution would require a big change in how the state collects and pays for its general funds, which set up the budget as a clear battleground.

When did this all start?

Rauner released his first budget proposal in February 2015, which included controversial changes in workers' compensation, cuts to higher education spending, significant cuts to Medicaid spending, and shifting public workers to lower pension benefit plans to decrease the state’s pension payments in the future.

The Democrats, led by House Speaker Mike Madigan, rely on a significant base of support from unions that represent public workers. They rejected Rauner’s measures, arguing it would be against their values as a party to incorporate any of Rauner’s reforms into a budget deal. Instead, they called for a tax hike to bring in more revenue to pay off pension obligations and other deficits.

The General Assembly passed several budget bills, the majority of which were vetoed by the governor. The Democrats held a supermajority in both houses of the legislature, which meant Rauner couldn't push his budget through the legislature without Democrats' support. Lawmakers negotiated up until the first deadline to no avail, and entered the state’s first year without a budget on July 1, 2015.

What is each side putting on the table?

Positions have evolved over two-plus years of debates, but the general contours of the impasse revolve around the following issues.

Rauner wants:

- A permanent property tax freeze

- Legislative term limits

- Changes to the state's workers' compensation payments

- Pension cuts that include new pension promises for workers hired in the future

Democrats want:

- Changes to the income tax structure

- To charge sales tax on a wider array of services

- Removal of some corporate/personal income tax loopholes

- A higher minimum wage

Other major issues include changing the school funding formula, independent redistricting, and a slew of budget cuts. The current Democratic proposal that hits the Senate today includes $3 billion of cuts.

Who are the key players?

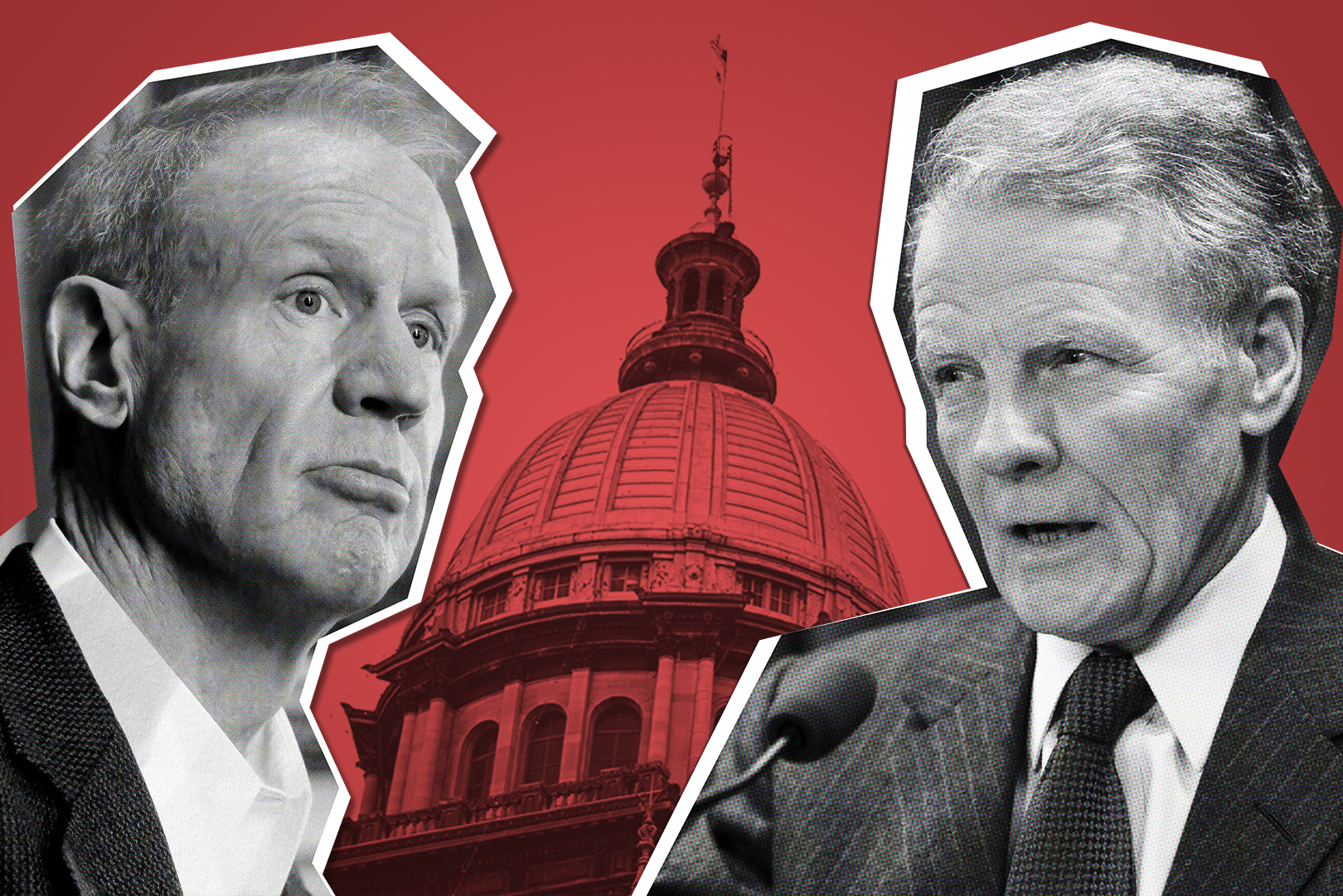

Much of the impasse is between Gov. Bruce Rauner and House Speaker Michael Madigan, who are the de facto leadership of each of their parties. John J. Cullerton, president of the Senate and Democrat, plays a quieter role. But Whet Moser has noted that it’s worth watching policy documents that come out of his office, particularly related to pension reform, to get an insight into what may be up for negotiation from Democrats in the Senate.

Is this all just political bickering?

Not completely. Illinois has real financial issues, both in its regular budget and in its pension payments. The key factor, say tax experts, is a structural deficit. In previous years, a series of poor decisions have only made it harder to pay off the state’s debt, kicking the can down the road.

What are the larger issues we're dealing with here? How long has Illinois been in financial trouble?

One major factor is the state's tax structure. Illinois is one of the few states that has a flat income tax, meaning everyone is taxed the same rate regardless of their income, which critics say keeps the state from benefiting as some residents get wealthier. The state also excludes a wide range of services from its state sales tax, which experts say is a missed opportunity to increase state revenue. As the economy in Illinois has grown, these two tax structures have kept the state’s revenue from growing alongside it at a similar rate, though needs for state services have also grown.

That left public officials with several unsavory options: raise taxes to increase revenue, cut spending on services, or cut spending on pensions. State officials chose the latter, and the unfunded pension liability grew. Then in 1994, as the pension liability reached about $17 billion, then-Governor Jim Edgar made a plan to have pensions 90 percent funded by 2045. That would require a huge jump in payments, but legislators at the time scheduled that jump to begin in 2010, 15 years after they passed their pension plan.

In 2011, to help ensure there'd be enough funds for these increased pension payments, the legislature increased state income taxes for four years. But just as Rauner came into office, that short-term tax increase expired, leaving the state government with ballooning pension payments and no clear new source of revenue. That's how the table was set for the budget showdown.

Today, Illinois owes $130 billion in state pension debt to its five state pension systems, a payment that the state enshrined in its 1970 constitution, making it incredibly difficult to renegotiate. There’s also more than $50 billion in unfunded health-care benefits for retired public workers.

Does that mean no one has gotten any funding from Springfield?

Not at all. Illinois is still spending money (more than it's taking in, in fact) through three main avenues. First, there's money we've already promised to spend, known as continuing appropriations. Then, there's money we're forced to pay due to court decisions. Last, there is a small percentage of spending (10 to 33 percent, depending who you ask) that's gone through the traditional legislative process, known as stopgap funding.

But plenty of other areas have not received money that they expected to get. For many state agencies this has meant purchasing services on credit, a plan likely to only make the state’s eventual debt burden worse. And suing the state has become a popular tactic; in May 2016, 64 service groups sued Rauner for not paying them a total of $100 million. As of April 2017, there were 17 school districts (including Chicago Public Schools) suing the state of Illinois for not providing enough funding for schools to meet learning standards.

Can they pass a budget any time?

There is a clear budget deadline every year, but legislators could pass a budget anytime they are in session. It does get more complicated when they pass a deadline—the threshold for how many legislators need to be on board to pass a budget is higher.

The legislative session adjourns on May 31, but the fiscal year doesn't start until July 1, so technically they could reconvene to pass a budget in June as well. Though lawmakers often negotiate into overtime sessions, around this time last year Rauner said it would be a waste of time to call a special session since the Democrats were not ready to vote on anything. Lawmakers ended up passing a stopgap budget in the 11th hour instead, which kept state government functioning and allowed schools to open in the fall.

Where are we now?

(Updated: June 29, 2017) As fiscal year 2017 comes to a close, Rauner and Madigan continue to throw political volleys back and forth in the press, while social service agencies and universities awaiting state funding had to make dire decisions about how to keep running. At the end of May, when Illinois blew its first budget deadline (thereby making it harder to get any legislation passed—we now need a three-fifths majority rather than a simple majority), Chicago's Whet Moser analyzed the motivations of Rauner & Madigan to figure out how we got here.

Democrats have accused Rauner of not negotiating in good faith, particularly because their budget proposal included a short-term property tax freeze—but Rauner has rejected it, in part because he says he’ll only sign a budget with a permanent property tax freeze. Rauner has thrown the blame back on Democrats, who control both houses of the legislature, for not "compromising" on the policy points that he has been pushing throughout his governorship.

Rauner then called a special session so lawmakers could work throughout the month of June to produce a budget before the end of the fiscal year, June 30—at which point, if the state still has no budget, Wall Street will likely downgrade the state's credit to junk status… particularly alarming considering how much debt we have. Oh, yes, and some school districts say they won't be able to open in the fall.

In other words, the stakes are higher than ever.

This all sounds crazy. What can I do about it?

While there are certain groups organizing to end the impasse, especially around college funding and social service agencies, the majority of Illinoisans (62 percent) feels unaffected by the impasse, according to an October 2016 poll by the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute.

That sentiment is misguided. Experts on both sides of the aisle agree that the lack of budget is making the state's financial problems worse, not least because the state is racking up an estimated $700 million in interest on unpaid bills in FY2017 alone. (For comparison, the state paid a total of $1 billion in interest on unpaid bills from 2004 to 2014, when we had budgets.) That doesn't even account for the human costs of lost services and the agencies that have closed due to the impasse.

A March 2017 poll by the Paul Simon Institute shows that Illinois voters are deeply divided on how to resolve the crisis. But there's a silver lining there, according to John Jackson, one of the designers of the poll:

When the voters are deeply divided, particularly in policy areas where the divisions are close, the office holders are given more leeway to fashion workable solutions to problems like the budget impasse, and then explain them and sell them to the voters, which is an obligation of leadership in a representative democracy.

Think it's time for your lawmakers to take up that "obligation of leadership"? Contact them and let them know you feel the impact of the impasse, and you're ready for them to find a workable solution.

Jamison Pfeifer and Alice Yin contributed reporting.