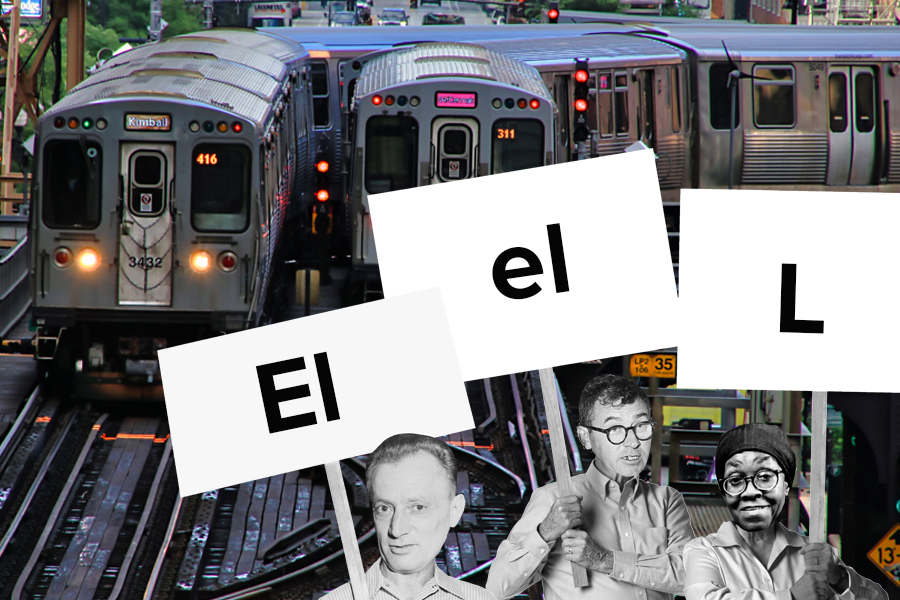

How, exactly, do you spell the name of the trains that travel around the city on elevated tracks? It's a debate that goes back to the 1890s, when the system began operating, and it turns out that even Chicago's greatest authors disagree.

James T. Farrell, author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy — probably the most 'Chicago' set of books ever written — referred to the trains as "the el." As in:

"Studs glanced around for a woman, wondering how he'd never before thought of the possibilities of getting against one in crowded el trains."

So too did Nelson Algren, whose name adorns a short story prize awarded each year by the Chicago Tribune, although he disagreed with Farrell on the capitalization. In The Man with the Golden Arm, Algren wrote:

"The Logan Square El rumbled up with the spring's last snow rusted along its roof."

But Gwendolyn Brooks, for many years the poet laureate of Illinois, used a different spelling. In her poem "of DeWitt Williams on his way to Lincoln Cemetery," which appears in her collection A Street in Bronzeville, Brooks wrote:

"Down through Forty-seventh Street:

Underneath the L,

And — Northwest Corner, Prairie,

That he loved so well."

Granted, poets have to be more economical in their writing than novelists, which may be why Brooks omitted the extra letter. (This magazine, for what it's worth, also uses L.) But three of Chicago's greatest writers used three different spellings for the CTA's rail system: el, El, and L. If they can't agree, then what's the answer to this eternal Chicago debate?

(I also searched in Saul Bellow's Ravelstein, but could find no references. University of Chicago professors don't take public transit, apparently.)

Bill Savage, a lifelong resident of Rogers Park, prefers El. Savage teaches English at Northwestern, but more importantly for his Chicago bona fides, he used to tend bar at Cunneen's on Devon Avenue, where a clock with Richard J. Daley's face on it still marks the hours until closing time.

Earlier this month, Savage wrote this on Twitter:

Hate to stir the ashes of this perennial argument among Chicagoans: it was "El" for Nelson Algren and James T. Farrell and other poets and writers, and so it's "El" for me; folk usage trumps officially-designated discourse for me every time. Meet at Cloud Gate to discuss . . . https://t.co/4JjYgMUx9l

— Bill Savage (@RogersParkMan) 7 May 2019

At least two contemporary Chicago literary celebrities agree with Savage, too. Here's Audrey Niffenegger in The Time Traveler's Wife:

"I take the Ravenswood El to Dad's apartment, the home of my youth."

And Rebecca Makkai in The Great Believers:

"On the way to the El, Charlie said, 'If you have to have a hot intern, at least it's a Mormon virgin.'"

In literary style, at least, "El" seems to be the preferred usage. But is it correct?

According to the CTA, it's not. Back in 2015, the the transit authoriy weighed in on Twitter with a spelling different than Farrell's, Algren's, and Brooks's: 'L,' in quotation marks. That's the usage that appears on maps in el/El/L/'L' stations.

Tweeted @cta:

@DaraKaye Definitely ‘L’.

— cta (@cta) 14 November 2015

The term "el" can be short for "elevated railway" generically, but our system has used 'L' since the 1890s. This proper, official nickname extends to elevated, at-grade, and underground tracks, and is used on official CTA materials.

Authors will probably continue to use El, and they probably should. On a printed page, the stand-alone letter L is confusing, especially for readers unfamiliar with Chicago: It looks as though it could denote a particular train line. In New York City, which assigns letters to its subway routes, the L train runs from Eighth Avenue in Manhattan to Rockaway Park in Brooklyn. (Also, in Chicago, the letter L has the negative connotation of appearing on blue flags after Cubs losses.)

When it comes to official usage, though, El supporters are going to have to take the L. It's the CTA's system, and the CTA can call it whatever it wants. No matter how we spell it, though, I can guarantee you all Chicagoans pronounce it the same.

Comments are closed.