I agree with the Sun-Times's Mark Brown on the irrelevance of the accusations against Herman Cain to the 2012 presidential race (although Cain may harbor future political ambitions; he's run for both president and Senate before). But I don't agree with this:

The stakes are too high. Cain’s credentials are too thin. The Republican Party is too white.

Cain's credentials aren't as thin as he typically gets a lack of credit for. Yes, there's the pizza thing, but he was also a chair of the board of directors for the Kansas City Fed, as Dave Weigel explains. He was an advisor to the Dole/Kemp campaign, and later Steve Forbes. Like Ronald Reagan, Cain cut his political teeth as a business lobbyist and as a speaker; Cain just happens not to have held elective office, though he's conducted two campaigns. His credentials are still thin for POTUS—whose credentials aren't?—but "pizza guy and talk-radio host" is a bit reductive.

And I don't think the GOP is "too white." As Brown himself admits, Colin Powell would stand a very good chance. (I think he'd win, given the lack of enthusiasm for Romney.)

No, the thing that will doom Cain has nothing to do with race or sex. It's his tax plan, which would raise taxes on most income brackets. It's not particularly well understood so far:

Two-thirds of likely Iowa Republican caucusgoers earning less than $50,000 a year believe they personally would be better off or in the same situation under Herman Cain’s 9-9-9 tax plan, The Des Moines Register’s new Iowa Poll shows.

[snip]

The bottom line: A family with an income level of $40,000 to $50,000 would pay $3,407 more a year in taxes, while families making $500,000 to $1 million a year would pay on average $80,315 less, according to the Tax Policy Center.

This has less to do with financial ignorance than the fact that his tax plan hasn't been put through the rigors of the primary season, and the general clutter of GOP candidates (can't we at least vote Santorum and Gingrich off the island?). It's still the part of the presidential campaign where heretical ideas can not only get aired but can also poll well—which is fine, it's the only interesting part of the long slog, like getting to see the rookies at spring training, and the polling that comes out of it is about as reliable as Josh Vitters's spring numbers. We've been through this with Cain's old advisee Steve Forbes: a flat tax has its appeal because of its simplicity, though it takes a fair amount of optimism to believe that simplicity wouldn't immediately get shot full of loopholes. (I'm trying to picture what Cain would do with a national sales tax in his old job as a restaurant-industry lobbyist.)

And in fairness to the theoretically financially ignorant, the calculations aren't exactly easy; converting the drop in your federal income tax to the implementation of a national sales tax isn't a back-of-the-napkin calculation, and most people have better things to do than run their consumption expenditures through the calculator of whoever happens to be running second in GOP polling, three months before the first primary.

Eventually these more radical ideas get trimmed off (cf. Ron Paul). A tax plan that would fall heavily on the middle class stands no chance in the teeth of an ongoing recession.

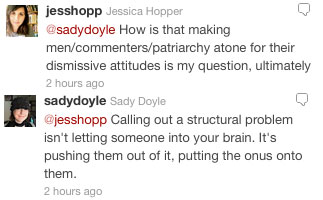

The accusations against Cain are more significant in relation to sexual harassment, which is why yesterday I was much more interested in following the #mencallmethings Twitter discussion, kicked off by writer and hashtag genius Sady Doyle. I tend to be more interested in the everyday manifestations of phenomena—walking dully along—more than the headline-grabbers, so gender relations are no exception.

Doyle's idea to have female writers share the misogynist abuse they receive over the Internet created a grim gapers' block on my Twitter feed. She explains:

Being afraid of your own in-box matters. Deleting your blog because that’s the only way for you to have a normal, non-hate-filled life matters. “Accepting” that continual, virulent, hateful misogynist abuse is a pre-condition for being a lady who talks about thing, or for challenging sexism in any way, no matter who you are: That matters.

It created an valuable dialogue, for instance between Doyle and my former Reader colleague Jessica Hopper:

As it applies to Internet incivility generally, I tend to side with Doyle: that people are more likely to deal with the garbage inside their heads when it's not sanitized, though I don't claim certainty on the issue. But there's another problem that's a serious issue for Internet denizens like myself, that emerges in a post by Jezebel's Anna North:

Interestingly, I'm less likely to get such insults in real life. It's not that it never happens — occasionally men on the street have called me a bitch when I don't respond to their catcalls. And other women I know have been exposed to far worse verbal abuse from strangers. Still, I'm far from the first to notice that the Internet gives people a sense of anonymity that allows them to say things they might never say to someone's face.

It's that "in real life" that's a point of tension for me. For some of us the Internet is "real life": where we spend much of our social time, where we earn our living. It's as much the workplace and a hangout as the office or the corner bar. (Sometimes I only recognize who a person is IRL when I'm introduced to them by his or her Twitter handle.) Which is good and bad for different reasons, but it is what it is, and it's increasingly—for lack of a better word—reality. The Internet is still a very young medium, so it's unsurprising that we're still learning how to integrate it intellectually and emotionally into our daily existence. Hopefully the way we treat each other on it will catch up.

Photograph: johntrainor (CC by 2.0)