Update: Rep. Mitchell explains:

“Time and time again, downstate is getting the short end of the stick,” he said.

Er, about that stick, and who gets what end, see below.

Via @krisvire and @ourmaninchicago:

WHEREAS, The State of Illinois is functional to the extent that its people agree on politics, society, and economics; and

WHEREAS, The people who constitute a majority of Cook County and the people who constitute a majority of the other 101 counties in Illinois hold different and firmly seated views on these important questions

I think you see where this is going. Meet House Joint Resolution 0052, filed today by Rep. Bill Mitchell of historic downstate Decatur.

I understand entirely where Mitchell is coming from. I'm from Virginia, and when I tell people that, the conversation goes like this:

Oh, from around DC?

No, Roanoke.

Oh, the Lost Colony!

No, that's Roanoke Island. In North Carolina. Roanoke is like five hours southwest of DC.

The Shenandoah Valley?

No, farther.

What's it near?

It's not really near anywhere.

So I get it. But aside from the politics of geographical resentment, I was curious what Mitchell's bill would mean in a speculative fantasy governmental sense. I think this is the usual perception, as exemplified by a letter to my former colleague Cecil Adams (emphasis mine):

Chicago, Chicago, Chicago — I'm sick of hearing about Chicago! Chicago problems, Chicago politicians, Chicago in the White House, and it just goes on and on. I think Chicago should secede from Illinois. Sure, us downstaters would lose Chicago's tax revenue, but we'd also be far less likely to have people like Blagojevich for governor, besmirching Illinois' good name.

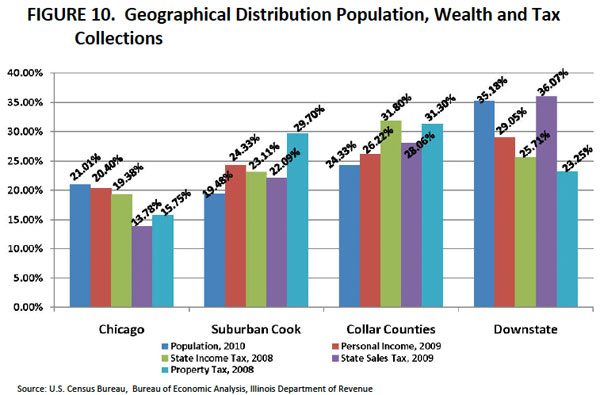

Yes, Chicago does generate much more tax revenue than downstate, if by "Chicago" you mean "Cook County," which is true for the purposes of Mitchell's bill. But Chicago also has lots of people. The golden goose is the collar counties: low density, lots of wealth, fewer services, while having the advantage of proximity to Chicago and all that entails. In recent history, the collar counties have been the only regional exporter of tax revenue:

As in any negotiation, the uncomfortable question is who gets the better part of the deal. Downstaters have long believed Chicago drains resources from the hinterland, especially for welfare spending. Chicagoans complain that downstaters waste money to build highways in sparsely populated areas. Collar county leaders, citing the tax load, whine that the other regions take advantage of the hard-earned wealth of the suburban middle class.

The Legislative Research Unit found in 1987 that the collar counties paid more proportionately in taxes than either downstate or Chicago and received less back in spending for state programs. That did not surprise political economists James Fossett and Fred Giertz. Governments, after all, are in the business of taking in taxes and redistributing the resources, generally from the more prosperous to those less so. Even greater redistribution might well be in order, say Fossett and Giertz: "Considering the severity of their problems, Chicago and other hard-pressed areas are receiving relatively less state funds from a number of program areas, while the prosperous areas are receiving relatively more. The state appears to be spreading funds more broadly than the distribution of social and governmental problems suggest is desirable."

That study found that the collar counties "paid 46 percent of the taxes but received only 27 percent of state spending. Downstate was the big net beneficiary, paying 33 percent of the taxes while receiving 47 percent of spending. Chicago paid 21 percent of the taxes and received 25 percent of the spending."

The authors add: "The research has not been updated, reportedly because of political fallout from the 1987 report."

The collar counties—Lake, McHenry, Kane, Will, and DuPage, not including suburban Cook—continue to pay more of the state's tax burden, as a percentage, than their population as a percentage of the state's population (PDF):

Downstate's sales-tax burden surprised me, and it surprised author Joe Sculley too, but he's got a compelling explanation:

However, if wealth is indicative of state sales tax revenues, then why do Downstaters pay so much in sales tax (36.07%), but rank much lower in personal wealth (29.05%)? The answer may lie, in part, to gasoline consumption and vehicle sales. Downstate has 35.18% of the total state population but represents 43.58% of all vehicle registrations (see Figure 6). This suggests that Downstaters are more dependent on motor vehicles than their counterparts in Metropolitan Chicago. More miles are traveled by vehicles in downstate Illinois per resident, as well as interstate travelers, than in the more geographically compact city and its suburbs. Our suggestion of sales tax on gasoline and motor vehicle purchases negatively affecting Chicago’s share of sales tax distribution is reinforced with downstate’s higher sales tax contribution.

As a city resident, this makes sense: my wife and I have a car, but we drive about once or twice a week, rarely more than a few miles at a time. When I lived in the rural exurbs of Roanoke, I put at least 40 miles on the car a day. Gas is really expensive in Chicago, but if you live there you generally use a lot less of it.

Looking at the geographical distribution of tax revenues, the idea that the collar counties pay more in taxes than they receive in state spending seems plausible, provided the general distribution of state spending hasn't changed much; it's very much not the case with downstate Illinois. So if Bill Mitchell wants to secede from Chicago, or wants to make Chicago secede, he better hope that the "people who constitute a majority of Cook County and the people who constitute a majority of the other 101 counties in Illinois hold different and firmly seated views on these important questions," different and firmly seated enough to peel off the not-entirely-red collar counties. They might have more cultural affinity with downstate, but fiscally it's kind of a wash.