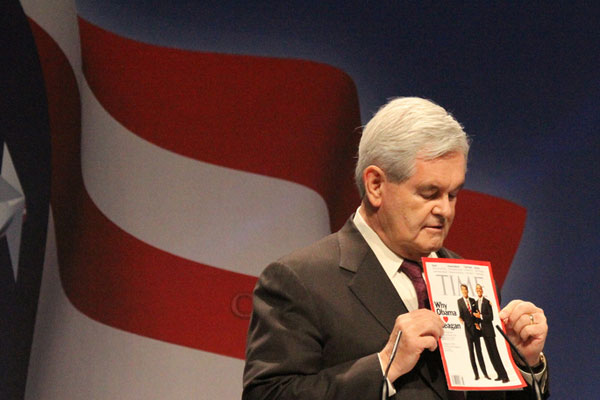

Newt Gingrich, the GOP not-Romney of the month—less than two months to go until it actually starts to matter!—is in the news for his atavistic ideas about child labor:

"Most of these schools ought to get rid of the unionized janitors, have one master janitor and pay local students to take care of the school. The kids would actually do work, they would have cash, they would have pride in the schools, they'd begin the process of rising."

This reminded me a bit of an excellent piece a friend of mine wrote for for Washington Monthly about the history of the foster-care system and why he chose to get into it:

Foster parenting had been in the back of my own mind since my family first started telling stories about my grandfather. He went into his first foster home in 1932, when he was twelve years old. The “orphan trains” that brought an estimated 200,000 big-city children to the farms of the Midwest since 1854 had only stopped running three years earlier. In agrarian America, home-based foster care often functioned as a way to match orphaned or abandoned children with homes that needed additional labor. This approach, mercenary though it may seem in our more sentimental age, often counted as a meaningful improvement over orphanages and homelessness. (The population in foster homes did not exceed the population in orphanages until 1950.) My grandfather, whose biological mother had herself lived in an orphanage for five years, did not, however, appreciate the historical dialectic at work. He ran away from a series of foster homes where he had been housed in barns and worked like a hired hand. Then he landed with a pious Roman Catholic family in Kiel, Wisconsin. There, the only woman he ever called “Mother,” whom he met when he was fifteen, prioritized his graduation from high school over farm chores. What they had managed to do for him, I wanted to do for someone else.

Yesterday's farm family will be today's unbalanced school budget, should Newt become president (he won't).

The funny thing is: Japanese schools do this, kind of, as I learned when I was reading up on the debate about school-day length and other countries' educational models.

At the end of the academic day, all students participate in o soji, the cleaning of the school. They sweep the classrooms and the hallways, empty trash cans, clean restrooms, clean chalkboards and chalk erasers, and pick up trash from the school grounds. After o soji, school is dismissed and most students disperse to different parts of the school for club meetings.

Perhaps because I attended two schools with substantial work components—it's a long story, but for my first two years of college I went to school on a ranch, where my favorite job was washing dishes—the idea of integrating physical work and education seems appealing to me. But in Japan, o soji or gakko soji is different from Gingrich's brutally utilitarian plan.

This lunch routine contains several moral messages: no work, not even the dirty work of cleaning, is too low for a student; all should share equally in common tasks; the maintenance of the school is everyone's responsibility. To underline these messages, on certain days each year the entire school body from the youngest student to the principal put on their dirty clothes and spend a couple of hours in a comprehensive cleaning of the school building and grounds.

It's a concept grounded in philosophy and history, instead of economics:

It has its origins in the Buddhist concept of purification; and actually goes far beyond the simplistic notion of maintaining clean and tidy school facilities. For some Japanese educators, Gakko Soji has been viewed as an essential school experience that encourages a child's sense of responsibility, cooperation, cleanliness, interpersonal and socialization skills, and duty towards the community and society. This component of education in the Japanese curriculum includes emphasis on acquisition of well mannered behavior in the social context; respect for law and order within the society; and a sense of social duty and responsibility. The school maintenance program, Gakko Soji, is seen as one of the most effective school experiences for providing lessons in the three main objectives of moral education.

Does Gingrich's idea go too far? Maybe it doesn't go far enough:

Most Japanese schools don't employ janitors, but the point is not to cut costs. Rather, the practice is rooted in Buddhist traditions that associate cleaning with morality—a concept that contrasts sharply with the Greco-Roman notion of cleaning as a menial task best left to the lower classes.

[snip]

At lunchtime, the students even don hairnets and help serve and clear away dishes from the midday meal. "Cleaning is just one part of a web of activities that signal to children that they are valued members of a community," says Christopher Bjork, an educational anthropologist at Vassar College.

What rankles about Gingrich's idea is that it leaves menial tasks for the poor, reinforcing existing divides. But what's good for poor students might be as good, or better, for rich ones.

Photograph: markn3tel (CC by 2.0)