A fascinating case recently went in front of the Supreme Court: Perry v. New Hampshire, at the heart of which is the reliability of eyewitness testimony. Slate's excellent legal analyst Dahlia Lithwick explains:

The case involves an alleged car break-in and a witness who offered the cops a less-than-satisfying identification—it was a “tall black man”—then voluntarily pointed to the suspect who was standing outside her apartment window with the police. (Later, at the police station, the witness was unable to identify the defendant from a photo lineup). But the police did nothing wrong or suggestive, which arguably makes the case different from all those 1970s precedents which sought to deter police misconduct. In Perry the question is whether, absent police manipulation, the defendant has a constitutional right not to have unreliable eyewitness evidence introduced at his trial.

It's an interesting case, but based on oral arguments and the justices' questions, Lithwick cautions not to expect much. Which is the same conclusion the New York Times's Adam Liptak came to before the case was presented:

“It is exciting that the court has actually taken an eyewitness ID case for the first time in many years,” Professor Garrett said, “even if it might be the wrong case on the wrong issue.” The justices are likely to rule only about which kinds of eyewitness identifications warrant a closer look from judges — just those made after the police used improperly suggestive procedures or all problematic ones?

[snip]

The state of the law is thus likely to remain jumbled. On the one hand, the court has said that the due process clause of the Constitution requires the exclusion of at least some eyewitness testimony on the ground that it is unreliable. On the other, judges are told to use a two-step analysis involving the weighing of multiple factors that in practice allows almost all such evidence to be presented to the jury.

So if it's largely an academic question, 1) who cares? and 2) what does this have to do with Chicago? Well, the city and state, thanks in part to its record of convicting the innocent that led to the death-penalty moratorium, took a long look at the question of eyewitness identity back in 2006, and its conclusions have been controversial but persistent. In the wake of the governor's Commission on Capital Punishment, the state undertook a year-long test of a sequential, double-blind method of eyewitness identification, as opposed to the traditional, simultaneous method (PDF):

Though the protocols for the sequential double-blind procedure are not yet standardized, this method generally involves showing the photos one at a time rather than side-by-side, with the witness required to make a decision on each photo before viewing the next one. The “double-blind” component requires that the lineup be conducted by an administrator who does not know which photo or live participant is the suspect and which are the fillers or “foils.”

Here's the logic behind the sequential method:

Researchers generally have attributed the reduction in false identifications associated with the sequential method to elimination of “relative judgement,” which is described as comparing the photos to each other rather than to the witness’s memory and then picking the one closest to the offender, even if it is not the actual offender.

[snip]

Showing the photographs all at once is like giving the victims one multiple-choice test where 'none of the above' is not really an option. Showing the photographs one at a time is like giving the victims six true-or-false tests.

The problem seems to be whether jogging the memory with an array of pictures aids recall or gives a false sense of confidence. What the Illinois study found was that the sequential, double-blind lineups "resulted in an overall higher rate of known false identifications than did the simultaneous lineups. When broken down among the three jurisdictions, Chicago and Evanston, which both conduct photo and live lineups, experienced a higher rate of filler identifications with the sequential, double-blind procedures; Joliet, which conducts only photo arrays, showed no statistical difference in the filler identification rates of the two methods…."

But the study received immediate and ironic pushback, as Reason's Radley Balko describes:

Mecklenburg’s report was widely derided by psychologists and criminologists for its lack of academic rigor and biased methodology. The critics’ complaints are too numerous too recount here, but the Mecklenburg report's most egregious error was that it calculated a witness’s selection of the police suspect as a “correct” identification. Thus the report counted every Illinois DNA exoneration as a “correct” identification. That’s a considerable oversight, given that the reason the Illinois legislature commissioned the report in the first place was as a response to the state’s high-profile string of wrongful convictions.

The Mecklenburg Report’s main effect was to slow the growing momentum for reforming the way eyewitness testimony is solicited and used in courtrooms. Though it has since been largely discredited, the damage was done.

Among the critics was eyewitness-testimony expert Gary Wells of Iowa State, who immediately laid out his concerns with the study in a memo (PDF). Wells also just weighed in on Perry v. New Hampshire, giving statistical weight to concerns about eyewitness testimony (PDF):

My own work has tried to address this problem by discovering better ways to collect eyewitness identification evidence and working with jurisdictions to reform how lineups are conducted. That has had some success. But, our most recent work that tested eyewitness identification evidence with actual eyewitnesses to serious crimes in San Diego, Tucson, Austin (TX), and Charlotte (NC) shows that between 30% and 40% of witnesses who make an identification mistakenly identify a lineup “filler” even when the best procedures are used. And, as shown by the Innocence Project, 190 of the first 250 DNA-based exonerations in the U.S. were cases involving mistaken eyewitness identification. Controlled laboratory studies of eyewitness identification, conducted by myself and scores of other social scientists, have long shown that mistaken identifications are quite common.

As Lithwick and Liptak note, eyewitness testimony has been the subject of extensive research over the past three decades: "there is no area in which social science research has done more to illuminate a legal issue. More than 2,000 studies on the topic have been published in professional journals in the past 30 years." Meanwhile, as the revolution in eyewitness testimony continues slowly and haltingly, law enforcement has shown a willingness to rexamine other forms of evidence based on disputed science. The best example is the extraordinary work of Maurice Possley and Steve Mills on the Cameron Todd Willingham case (as well as that of the New Yorker's David Grann), which showed the conviction of Willingham was based on outdated science:

"At the time of the Corsicana fire, we were still testifying to things that aren't accurate today," he said. "They were true then, but they aren't now."

It's a mindbending statement that gets to the eerie ramifications of Perry v. New Hampshire: how much we can believe our own, potentially lying eyes.

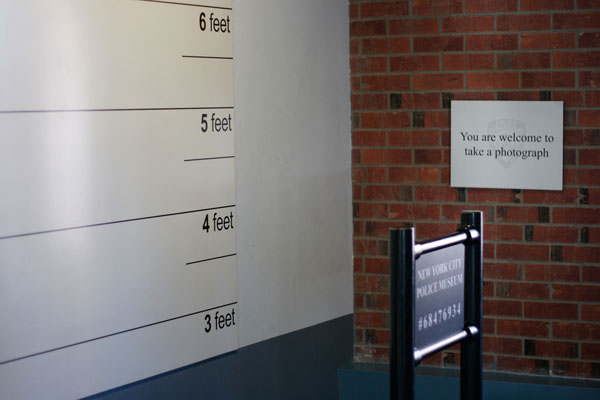

Photograph: Marcin Wichary (CC by 2.0)