Today Ben Joravsky has a good post on the Emanuel administration's privatization of jobs. The problem he focuses on might not be what you'd guess:

As I wrote a few weeks back, the mayor is farming out the water call operation to NTT Data, a firm based in Japan. NTT will hire part-time workers who apparently get no health or pension benefits and have no obligation to live in Chicago, whereas city employees, including the current water call crew, have residency requirements. The mayor claims the move will save taxpayers $100,000 a year.

In other words, Emanuel will essentially take money that's been going to pay people who live in Chatham, South Shore, and other local communities and send it to Japan. All in the name of helping the taxpayer.

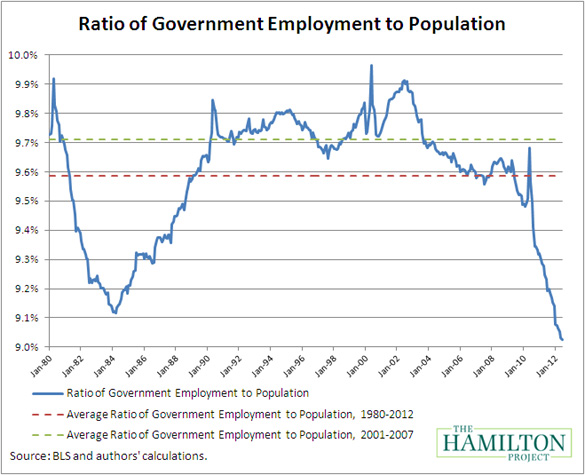

It raises some difficult problems that aren't unique to Chicago; in fact, they're critical to the current nationwide political and economic situation in America. Governments are cutting headcount at all levels, because of revenue shortfalls and debt problems. But jobs are jobs, so a public-sector layoff creates the same unemployment that a private-sector job does. Higher unemployment means less money to spend, which means less revenue, which means less economic activity. Nationwide the unemployment rate would have been 7.1 percent earlier this year without government layoffs.

By percentage of the population, we haven't seen anything like it since the Reagan administration (via):

It's a particularly critical issue for blacks, for whom government employment has long been a reliable source of middle-class salaries:

The central role played by government employment in black communities is hard to overstate. African-Americans in the public sector earn 25 percent more than other black workers, and the jobs have long been regarded as respectable, stable work for college graduates, allowing many to buy homes, send children to private colleges and achieve other markers of middle-class life that were otherwise closed to them.

Blacks have relied on government jobs in large numbers since at least Reconstruction, when the United States Postal Service hired freed slaves. The relationship continued through a century during which racial discrimination barred blacks from many private-sector jobs, and carried over into the 1960s when government was vastly expanded to provide more services, like bus lines to new suburbs, additional public hospitals and schools, and more.

Earlier this year, Joravsky and Mick Dumke dug into city payroll records to find where city government jobs had been lost. Since they had data but no map, I decided to map it (the gradient represents raw job losses, not percentages):

And for comparison, where city employees live in 2012, by zip code. It's interesting that there's sort of an outer-outer ring on the south, southwest, and northwest sides.