The City of Chicago has long done data well, and in turn that's encouraged a flourishing open-data community—the CLEAR system begat the Chicago Crime Map, which begat EveryBlock, and a number of excellent open-data projects have flourished, like Open City Apps and the Tribune's own web-apps team. Cook County has been a different story, as anyone who's encountered the court system can attest. When Dorothy Brown was running for re-election as clerk of the court (she won handily), Mick Dumke told of his frustrations trying to get basic data from the court system:

Last July, after conversations with police officers, I thought I’d take a look at how many people were charged with unlawfully using guns in 2009 and 2010.

Silly me.

I followed protocol by first sending a formal request to the office of Chief Judge Tim Evans. It was quickly approved. I then forwarded the approval to Brown’s office, since I can't get the information anywhere else.

[snip]

At last, in December, I received an e-mail notifying me that the records—the public records I’d asked to see half a year earlier—were ready for me.

All I had to do was pay the clerk’s office $1,450.

I was informed that this was to cover the costs of the nine hours of research and programming it took Brown’s employees to extract the information from their computer system.

The county is developing an electronic case-management system, which has been a long time coming, and an example of how data-gathering isn't just a matter of getting information to the public; it's also critical to the functioning of government (PDF):

Under the current system, each day, judges receive a printout of cases currently on their docket. This “court sheet” gives them some very valuable information. It tells them what the first charge was in the case, the first date on the docket, the status of the case, the date that status was assigned, and the next scheduled court date.

Absent from this report, however, is any aggregate information or time series data that would allow a judge to quickly evaluate how well he is managing cases. Such measures are the “vital signs” that judges and administrators need to evaluate how well they are shepherding cases from initial filing to final disposition. Even an ambitious judge committed to resolving his cases quickly simply does not have the tools to evaluate his performance using “court sheets.” Moreover, the data system does not allow for digital inter-agency information sharing, thereby limiting potential for evidence-based cooperation.

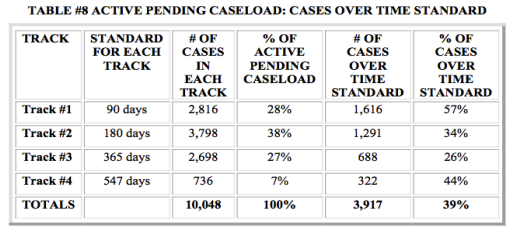

The Appleseed Fund unsurprisingly couldn't get data on current dispositions from the court, but as of 2007 cases tended to run long:

And that's expensive:

Because tens of thousands of defendants each year await disposition of their case while in Cook County custody, achieving felony disposition standards is of considerable civil rights and economic value. At any given time, about 90% of the 8,000 – 10,000 individuals detained in Cook County jail are awaiting trial at an estimated cost of $143 per day. Despite a 25.9% decrease in annual admissions between 2007 and 2011, an analysis authorized by the Cook County Sheriff determined that the average length of stay within Cook County Jail has increased by13.0%, from 47.9 days to 54.1. As a result, the jail’s average daily population fell by only 9.5% during the same period.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune