On the 25th anniversary of the death of Harold Washington—who died in the mayor's office the day before Thanksgiving—Gary Rivlin has been kind enough to let us run an excerpt of the new edition of his classic book Fire on the Prairie, recently published by Temple University Press. It's one of the best books I've ever read on Chicago politics. It's a remarkable portrait of Washington as a man and politician, and of Chicago during a time that would be unrecognizable today: when Chicago's city council was far from a rubber stamp but a place of open conflict with the mayor, of gridlock now more familiar on a national level (Rivlin captures Dick Mell arguing against a bond issue Mell supported in the abstract simply because it would reflect well on Washington). It's one of the most interesting and informative books written about the city, and well worth your time. For bonus Rivlin, check out the Reader's archive of his stories, especially one of my favorites, "The Night Chicago Burned." In the Trib, Rivlin and Larry Bennett (author of the introduction to the new edition and his own good book about Chicago) have a good piece on Washington's legacy, including his administration's forward-thinking economic development strategies. —Whet Moser

Long before sunrise, people jammed the sprawling grounds of the Christ Universal Church on Chicago’s south side. A pair of black women, both well past sixty, had been the first to arrive, there since five o’clock the previous evening. Others soon joined them as twilight gave way to a raw November night. Word had spread that select seats for Harold Washington’s funeral were to be had on a first-come basis and, with sleeping bags and wool blankets and other armaments against the cold, each took his or her place, partaking in a ritual more commonly reserved for the World Series and concerts featuring big-name musical acts. Thousands more arrived after sunrise—ten thousand people in all, according to the newspapers.

A soft steady rain fell the day Chicago buried Harold Washington. Along the route mapped out for the cortege, people leaned out of second-story windows peering into the distance. Tens of thousands stood on the street, waiting, two solid lines running the entire seventy blocks from chapel to cemetery. Three hundred cars crept by in endless procession, flowing like a creek between twin banks of people.As the procession approached the cemetery, the crowd was thicker still, five or six or ten deep, as at a downtown parade. Another three thousand stood at the edge of the cemetery waiting for the hearse. The crowds occasionally broke into a spontaneous rhythmic chant of the dead man’s first name: “Ha-rold. Ha-rold.” It was a startling sound, more familiar inside a baseball stadium as the fans pump their favorite during a do-or-die at bat. “Ha-rold. Ha-rold.” A politician.

The national news stories reporting Washington’s death stressed his color and the thirty-six days he spent in the county jail on a misdemeanor charge. These accounts also highlighted the ugly 1983 election that first brought Harold Washington to national attention, casting him as a symbol of the racial conflict besetting the nation’s great urban centers. Chicago’s deep racial divisions dominated Washington’s obituaries.

Yet Washington was far more rare than just a trailblazing black, his tenure notable for much more than the racial backlash his rule inspired. His victory revived a national black empowerment movement mired by splits and apathy. “His oratory, the use of words like a weapon—his style was very attractive to the black imagination,” one eulogizer said. “It was similar to the way Malcolm X captured the black community. He would face down white people in their own realm yet still keep his so-called black credentials.”

Most of those queuing up to view the cortege were black, but there were plenty of white, Latino, and Asian faces among the crowd. His was a black-led coalition, to be sure, but one based on issues that crossed racial lines: affordable housing, affirmative action, and other progressive totems. “He put people together who really were enemies of each other,” said another eulogizer. “That was Harold’s gift.” Around the country they could only dream of a Jesse Jackson–like Rainbow Coalition growing into a dominant political force; in Chicago, the country’s third largest city, the Washington coalition ruled for five years during the 1980s—the Reagan years. In a decidedly conservative era, Chicago was an intriguing anachronism, a beacon from the country’s heartland that projected into the future more encouraging possibilities.

Jesse Jackson was there when Chicago buried Harold Washington. Jackson had been in the Persian Gulf when Washington died, and although the 1988 presidential race was upon him, Jackson returned home. He had been all but banished during the Washington campaign of 1983, asked by Washington emissaries to leave town until after the election, but Chicago was where Jackson came of age politically. He was there when Martin Luther King Jr. and the first Richard Daley went toe-to-toe in the 1960s; his first run for political office was his 1971 mayoral bid. Jackson learned the ways of the Rainbow in Chicago; it was his goal to build the Washington coalition on a national scale. “God got a lot of mileage out of Harold Washington,” Jackson said at the funeral. The media estimated that somewhere between 200,000 and 500,000 mourners passed by Washington’s open casket in the days leading up to Washington’s funeral. Only 25,000 amassed in Memphis to view Elvis Presley’s. It may be crass to compare two famous men by counting heads at their funerals, but how better to make the point that the reaction to Washington’s death resembled the death of a celebrity more than that of a local politician? His mourners were not sobbing women throwing themselves at the foot of the king’s sepulcher. People of all races and ages abandoned themselves to spontaneous and unrestrained grief. In interview after interview, mourners spoke of Washington like a favorite uncle or a father figure. Love was on people’s lips and written in thick letters on cut-up cardboard boxes. A bearded white man wearing round wire-frame glasses held on his shoulders a child who held a pennant that read, thank you, mr. mayor. we all love you.

Wariness, cynicism, resignation to the lesser of two evils—around the country voters rarely feel something as mild as affection for a politician. What’s love got to do with politics?

–From Fire on the Prairie: Harold Washington, Chicago Politics, and the Roots of the Obama Presidency. Courtesy of the author and Temple University Press.

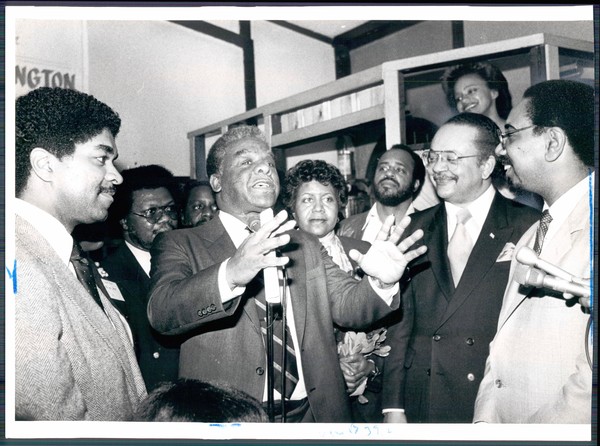

Photograph: Chicago Tribune