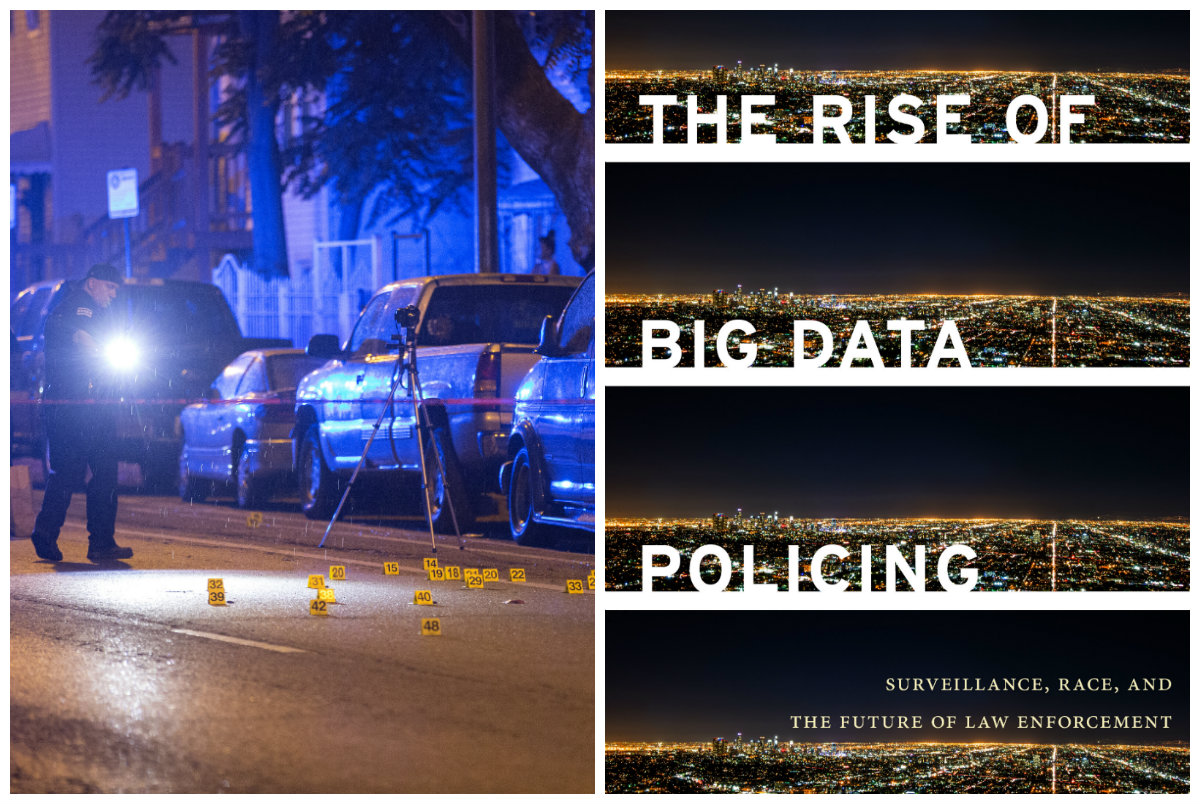

We are being watched, tracked, and targeted daily, according to Andrew Guthrie Ferguson, a professor of law at the University of the District of Columbia and author of the new book, The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement.

From facial recognition software to linked surveillance cameras to “heat lists,” police departments across the country are gathering data and using algorithms to predict future crimes and criminals. Ferguson says Chicago is at the epicenter of this new reality, “tripling down” on its predictive policing strategies like the Strategic Subject List—which scores individuals based on their likelihood to be involved in violence—at a time when other cities have been more cautious.

Chicago magazine spoke to Ferguson about Chicago’s use of big data policing and his criticisms of the strategy.

How has big data changed policing in places like Chicago?

If you’re a police officer on the street and you stop someone and run their name through the system and see they have a [risk of violence score of] 500, which is the highest score on the heat list, you’re going to treat them differently. You’re going to be more careful and you might use more force, and you might actually be wise to do so. That’s a different world [than it was before] computers created a rank order list of the most threatening and the least threatening people in a community.

You need to be really sure about the accuracy of those numbers, because those threat scores are going to impact how police deal with the citizens they see.

How transparent should police departments be about their big data programs?

I think police departments do themselves a disservice by being so opaque about the process.

Right now, the [Chicago Police Department’s] algorithm is secret and it took a lot of effort to get the inputs public. I imagine if they released the algorithm, no one would really care, because the vast majority of people are not parsing algorithms. What they care about is, 'Does this system seem fair and how do you explain it to me?' And that’s why I think we need to have these accountability moments where the police chief gets up there and says, 'This is what we’re doing, and this is why we think we’re right. If you think some other inputs should be up there, that’s fine. Let’s have that conversation.'

But we don’t have that open dialogue about surveillance and control of policing because [policing has] always been a quasi-secretive entity. They might lose a small tactical advantage, but they are losing a huge legitimacy advantage by keeping all of this so nontransparent and so secretive and so unavailable for people to look at and critique.

In the book, you coin the term “bright data” as an alternative to big data policing. What is bright data?

I use [bright data] as a way to say there’s a real insight to big data that shouldn’t be thrown out just because we’re concerned about how it’s linked to a surveillance state involving the police. [Big data] doesn’t have to be controlled by the police.

I jokingly say, predictive policing might be a whole lot better without the policing part. Predictive analytics is helpful. It’s useful to see patterns of violence and crime and victims, but we don’t need to necessarily respond with policing. We may want to respond with social services and economic changes, education changes. And those things might be far more valuable than a policing response.

One of the sad ironies of the rise of big data policing in Chicago is that insight was recognized in the early iterations of these programs. There was a recognition that we want to be able to offer social services to individuals to get them out of this lifestyle and change the underlying patterns of crime and violence. But that part wasn’t funded in the same way as the policing was.

What keeps you up at night?

My real worry is because policing is so localized and fragmented, we’re not paying attention to how these new technologies are changing what police do every day, where they are going, and what they see their role as. And without that national conversation, we’re allowing the technology to get really far along without checking and asking some very basic questions: Does it work? Is it racially biased? Is it changing our laws and our privacy protections? And if it is at risk of doing any of those things, maybe we should have a democratic conversation about it to make sure that we, the citizenry, are OK.