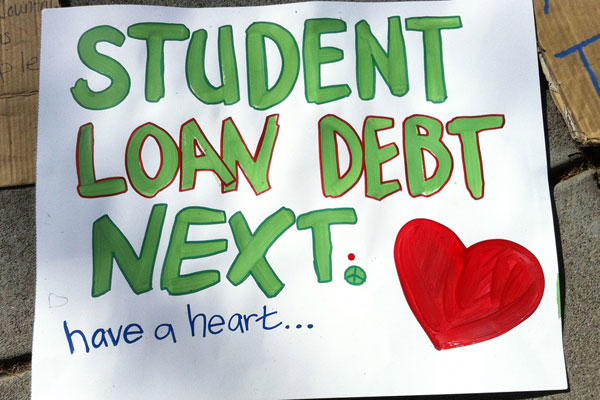

Today's big economic news is that the Obama administration has redoubled its student loan relief strategies: moving up the point at which debtors will have their loans forgiven, lowering the limit for income-based repayment, and offering a consolidation option at reduced interest. I think it's some evidence that Occupy Wall Street, with its emphasis on debt, has shifted the political narrative, with assistance from the wonks who have been pushing the debate (Obama's reference to student loan debt outpacing credit card debt has been floating around econ blogs for a long time now).

Nonetheless, the student loan world is so insanely complicated that you really need to read several articles to get a sense of what the administration's game is. Here's a good start.

* Update: How it originated with the Bush administration.

* "Obama moves to ease student loan burdens," Washington Post. It makes the important point of explaining where the money for this will ostensibly come from, which is the elimination of subsidized loans. I think what they mean here is not subsidy cuts in the sense of subsidized Stafford loans (the subsidy takes care of the interest while the student is in school) which were eliminated earlier this year for grad students to pay for Pell Grants.

* Instead, I think what they mean is this:

The “profits” from lending existed mainly because the revenues produced (as borrowers with high interest rates repaid their loans) significantly exceeded what it cost the banks and the government to make the loans.

[snip]

But now that the government itself is the sole provider of federal student loans, those revenues are flowing into the federal treasury, and it is clearer than ever before that the “profits” that would be redirected to deficit reduction and other purposes are coming from the borrowers themselves.

In short, it's the savings from cutting out the middle man—I think. Plus the interest rate on Stafford loans is set to double, so that may have something to do with it. Update: Here's some clarification from Libby Nelson of Inside Higher Ed: subsidies to banks eliminated; the effect of rate doubling.

* Why so many employed college graduates are struggling: "It's been a bad year to graduate from college," Washington Post.

* "The Student Loan Proposal: What It Might Mean For You," New York Times. This does a fine job of tracing what aspects of the reforms will be available to what borrowers; obviously, due to when different pieces of it are implemented, not everyone will be eligible, including myself. For instance, the loan consolidation aspect, which would reduce interest rates for borrowers, is only available to people with "split" loans, moving from "both federally guaranteed student loans and direct loans" into direct loans. But it's not available for people with just federally guaranteed loans.

* What's the difference? Here's an explanation from "Guaranteed Vs. Direct Lending: The Case of Student Loans" (PDF):

The Department of Education (ED) oversees two competing student loan programs: the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL, or guaranteed) program, and the William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) program. In the guaranteed program, which dates back to the mid-1960s, the government guarantees loans originated by private lenders against losses from default and makes supplemental payments to lenders. In the direct program, which began operation much more recently in 1994, the government directly lends to qualifying students.

* None of the reforms has anything to do with solely private loans.

* And it doesn't address the root of the problem: the tremendous increase in tuition expenses, which Benjamin Ginsberg attributes to school administrative bloat. One argument is that federally guaranteed student loans make the problem worse, since an industry whose payments are guaranteed hell or high water is under less pressure to compete on cost. On the other hand, it's a difficult scenario to design a debt system around—if you stop paying your mortgage or your car payment, people will take your house or car. They can't take your knowledge of particle physics or anthropology back.

It's comparable to medical debt, since hospitals aren't allowed to, say, send a repo man to re-open your wounds if you skip out on paying for your stitches. Not coincidentally, that's another form of debt that's central to Occupy Wall Street, not to mention legislatures around the country.

* Mike Konczal discusses the unique status of student loans, and how the new reforms won't help most of the people who have already driven up U.S. student loan debt, and asks, "how is this not setting up an entire generation for complete disaster?"

* Part of the reform is the Know Before You Owe program, from the Consumer Financial Protection Board, which aims to simplify financial-aid information; you can visit the site and send feedback on the info-sheet draft. It's a good start, but it's clearly intended for entering students, not exiting students.

In my experience, the former is the easy part; it's when you're out on your own with all sorts of loans from different sources and various, often exclusive means for consolidating and/or reducing payments that it gets impossibly complex. Which is why the income-based repayment aspect of this new round of student-loan reforms actually already exists and is profoundly underutilized.

One of the significant effects Elizabeth Warren had on the creation of the CFPB is a drive towards simplification of financial information, beginning with credit card statements. Know Before You Owe is great, but if anything, Know After You Owe is more important.

Photograph: a.mina (CC by 2.0)