Jens Ludwig, who teaches in the law, SSA, and public-policy departments at the University of Chicago, is the lead author on a fascinating new article recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine: "Neighborhoods, Obesity, and Diabetes—A Randomized Social Experiment." It arose out of Housing and Urban Development's Moving to Opportunity Program, modeled on the CHA's Gautreaux Assisted Housing Program and advanced by the work of Gautreaux lawyer Alexander Polikoff. About 4,500 women living in high-poverty public housing were randomly assigned to three groups, one given vouchers that could only be used if they moved to low-poverty neighborhoods and received counseling, one given unrestricted vouchers, and one control group. As you might expect, the randomized, longitudinal nature of the program has made them a well-studied cohort:

* "Moving to Opportunity: an Experimental Study of Neighborhood Effects on Mental Health"

* "The Early Impacts of Moving to Opportunity in Boston: Final Report to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development" (PDF)

* More studies than you can shake a stick at from the NBER

And so forth. This most recent study looks at narrow, specific outcomes: obesity and diabetes among the three groups. The results might be intuitively obvious, but they're pretty stark: "The prevalences of a BMI of 35 or more, a BMI of 40 or more, and a glycated hemoglobin level of 6.5% or more were lower in the group receiving the low-poverty vouchers than in the control group, with an absolute difference of 4.61 percentage points…. The differences between the group receiving traditional vouchers and the control group were not significant."

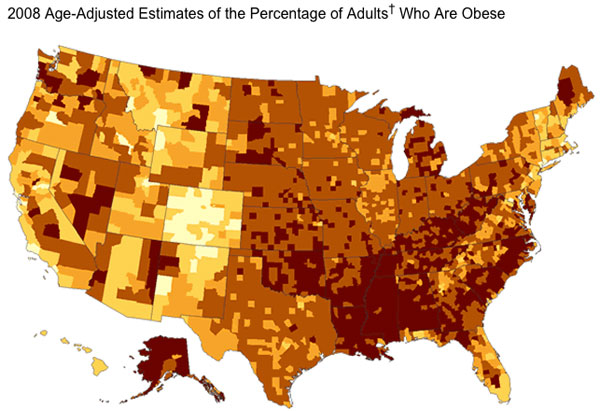

It's worth noting that this is hardly exclusive to urban areas. The county in Illinois that has the greatest problem with adult obesity is Macon in central Illinois, home of Decatur. Broadly speaking, it's a much greater problem in rural America.

One of the oddest things about that map are the divides along state lines: between Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky, for example. (Kentucky's Clay County, long one of the poorest in the nation, has an obesity rate estimated at over twice the national average, despite the fact that far southwestern Virginia is culturally and economically not dissimilar to eastern Kentucky and southern West Virginia. Western Louisiana and Eastern Texas I'm unfamiliar with.)

It's worth noting that the study by Ludwig et al doesn't attempt to assign any kind of causation, but the suggestions are pretty familiar:

Previous studies have suggested several pathways through which neighborhoods might influence health. Changes in the built environment (e.g., the addition of grocery stores or spaces where residents can exercise) might affect health-related behaviors and outcomes such as obesity. Proximity to health care providers might influence the detection or management of health problems. Neighborhood safety might influence exercise level, diet, or level of stress. Social norms for health-related behaviors may vary across neighborhoods.

The relationship between stress and obesity is particularly interesting, and has been the subject of some particularly rich medical research.