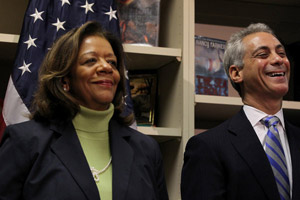

Jean-Claude Brizard, whose public presence dimmed during the teachers strike, left his post yesterday in an awkward-sounding mutual agreement:

Brizard said he talked to Emanuel about leaving after a Tribune report that the mayor wasn't happy with him.

In late August, amid heated negotiations between the district and the teachers union, sources told the Tribune that education and business leaders told Brizard that the mayor would blame him for letting the labor situation with teachers get out of hand. At the time, Emanuel denied that he was unhappy with Brizard.

"I think perhaps there were issues," Brizard said Thursday. "I call it a marriage that was perhaps imperfect. My style and personality are maybe not what the mayor wants."

At the time, John Kass called Brizard Emanuel's "human shield," presaging his exit: "One possible scenario: The teachers actually do go on strike, Brizard becomes the focus of all the bad news, parents who can't find day care begin to get furious and he soaks up all the negativity." You could say that's what happened—the teachers did go on strike, and Brizard left. But last week Alexander Russo made a compelling case that Brizard wasn't a particularly effective human shield, and was better served staying on.

City Hall needs Brizard to play good cop and provide continuity and bolster parent confidence. While it'd be fun in the short run to make Emanuel change leaders, CTU needs Brizard to stay in the background so that they can continue vilifying City Hall without any distracting changes of leadership. Plus which, any Brizard replacement would be the same or worse.

On the other hand, Seth Lavin predicted in June that Brizard would be gone in a year:

This week, for the first time, it became clear to me that Brizard has to go…. For Rahm, firing Brizard essentially means raising a white flag on his entire first year of school reform. Yet that’s actually become a less damaging alternative than the charade of acting like Brizard’s relevant or speaks for CPS.

Either way, given how Emanuel moved to the center of the teacher's strike as Brizard moved into the background, he doesn't make much of a scapegoat for the strike. For the time being, and for better or worse, Emanuel owns the situation at CPS, which has been the impression that a lot of people have received for awhile.

Anyway, that brings us to Barbara Byrd-Bennett, Brizard's permanent replacement. She's a veteran of New York's Crown Heights public schools, and later Cleveland and Detroit. One salient thing from her background seems clear: as the head of Cleveland's schools, she threatened to quit if the city moved from a mayor-appointed school board to an elected one, which she won support on from the local teachers union:

''To our great surprise, this has been a positive change,'' said Richard DeColibus, the union president. ''Barbara Byrd-Bennett has astonishingly high approval from our members, who believe she really understands them. I guess going back to an elected board would be a form of democracy. But the pure form of democracy didn't work so well, and the schools are getting better now.''

[snip]

Given those achievements, she said, she could live with the loss of voting rights inherent in mayoral control. ''As a woman of color, obviously, I've had to struggle with the question,'' she said. ''It's not something we can be cavalier about.''

While voting rights have historically been the agent of change for African-Americans, Ms. Byrd-Bennett said, in Cleveland, ''you can ask whether mayoral control has been the way to change the schools, and I think it has.''

But Chicago isn't Cleveland, which had a messy history with elected boards. But as a non-binding referendum on elected school boards goes on the ballot in 35 wards, Byrd-Bennett's experience there is something to keep in mind as a factor.

Byrd-Bennett came into an even tougher situation in Cleveland, with no money, historically segregated schools, and a 28 percent (!) graduation rate, and pushed through a tax increase, bringing the books in line within four years and rebuilding school infrastructure. What happened next? "Her declining popularity made her departure a political necessity, but it is disheartening, nonetheless."

After a seven-year tenure that saw finances settle, scores climb and Byrd-Bennett achieve national acclaim, this year will commence the dismantling of much of the system she worked so hard to build. Two levy losses in nine months have done more than demonstrate Byrd-Bennett’s own sinking appeal. They have proved that she must step aside to give the district a chance to succeed.

When Byrd-Bennett arrived in Cleveland, she found a school district rife with disorder and low morale, and an administrative staff weighed down by too many principals without talent or accountability. She put systems in place to measure success, and gave teachers the resources to achieve it. She did not hesitate to fire poor performers within the system, and worked tirelessly to persuade doubters outside it.

[snip]

Then the economy tumbled. State money slowed. Hundreds of teachers lost jobs. And the hard-won momentum began to reverse.

So Bennett isn't just a lifelong veteran of public schools; she also comes in with on-the-job experience in a tumultous, broke Midwestern school district, and the political fallout one can generate.