Most eyes were focused on the presidential debate last night, but in the meantime I read something that seemed to cause a bit of a stink on Twitter, particularly with the headline "Emanuel Blames Unions for Lack of African-American Jobs." The short of it is that there was a protest on the South Side on Sunday inspired by a businessman who noticed that a sidewalk-repair crew had no blacks working on it. Emanuel was asked about this on WVON, and said:

The question is, “Now that we’re investing, who’s getting the work and who’s working on it?”…Now we’ve got to make sure that the building trades, which there’s a history at, which have not been opened to African-Americans and Hispanics and others, and minority children, make sure they have a training program, so the jobs that we’re investing in, and finally doing after years of not doing, are open to everybody in the city to apply for, and have the skill set so they, too can have that work.

The teachers strike highlighted Emanuel's rocky relationship with unions, which will continue to be an issue. But from a historical perspective, Emanuel is right about this. Obviously it depends on how far back you want to consider "history," but the history of institutional racism in trade unions—in Chicago and elsewhere—is long, ugly, and did tremendous damage to the city from a racial and economic perspective. As Thomas Sugrue writes in Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North:

In the early twentieth century, northern blacks and leading civil rights organzations had been deeply skeptical about trade unionism as a strategy for black advancement. They had good reason. The American Federation of Labor had an abysmal record of excluding blacks from membership and, as a result, of keeping crucial sectors of the economy all-white. The pervasiveness of discriminatory practices in unions (from attacks on black "scabs" to the separation of blacks into inferior locals to the countenancing of racially separate job and seniority lines) made unionization a hard sell. Further hindering unionization efforts, many black elites cast their lot with white employers. The Urban League, which had as its primary task expanding economic opportunities, did so by accepting close, often paternalistic relationships with corporate leaders in exchange for a small number of jobs. The key part of this bargain was opposition to unionization. Upwardly mobile black ministers often curried favor with white philanthropists and business leaders, hoping to open a few well-paying jobs to members of their congregations. In Gary, Indiana, "the churches," lamented one clergy leader, "have become subsidiaries of the steel corporation and the ministers dare not get up and say anything against the company…." To break down the deep-rooted antiunion sentiment among blacks would require simultaneous efforts to overcome union-sanctioned racism and to wean black leaders from their dependence on white business.

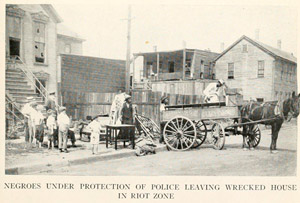

Industrialists used racial tensions and union segregation to their advantage, such as in the 1905 Chicago Teamsters' Strike, in which 21 people died, the second-deadliest labor conflict in the 20th century, during which mobs attacked black strikebreakers who were brought in to drive wagons. These racial dynamics of convenience evolved into concrete racial identities, and were a part of the evolution of early Chicago's melting pot of immigrants into color lines dividing "us" versus "them":

White-collar work in integrated settings, Drake and Cayton wrote, was broadly opposed by whites as a form of “social equality.” Unions, especially in the crafts, often barred African American entry into jobs, and industrial unions frequently acquiesced or colluded in leaving skilled, high-paying manufacturing jobs in white hands. Wisconsin Steel and Western Electric, on the far Southwest Side, graphically showed the difficulties of imagining unity at work and exclusion residentially and illustrated the difficulties facing antiracist trade unionists. In the area near those plants, [Lizbeth] Cohen writes, white employees feared African Americans “as co-workers—to say nothing of as neighbors.” Management in the factories, she adds, “respected community prejudice and did not hire blacks.” In this instance, as in more formal actions to enforce residential segregation, the category “white” came to unite and include a variety of immigrant groups.

Both the exclusion of African Americans and the inclusion of new groups of often despised immigrant European workers as white were decisive in defining these cross-cultural exchanges.

This took years to address; as Sugrue points out in his previous book, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, the UAW (a much more progressive union than the AFL) had to police its own members, who went on "hate strikes" throughout the 1940s and 1950s in an effort to keep black workers out of automobile plants. Not all of the mid-century union racism was "institutional" in the sense that it was actively encouraged at the highest levels of union leadership, but rank-and-file racism in some unions took on an institutional structure; Sugrue argues that the UAW on a national level was a force for good, but locals were wildly inconsistent in how they dealt with the subject of race.

It's long been a point of contention within the labor movement and with scholars of it. The late Herbert Hill, a white protege of Hannah Arendt who was the labor director of the NAACP before becoming a professor of Afro-American Studies at the University of Wisconsin, got into a tiff in the 1990s with Nelson Lichtenstein, the prominent UCLA labor historian, over racism in the nation's big trade unions. Hill accused Lichtenstein of whitewashing the racial record of the UAW and leader Walter Reuther, while Lichtenstein argues that Reuther faced tremendous headwinds and, as a relatively progressive labor leader, is held to a vastly higher standard than his peers. It's a bit of inside-baseball historiography, but Lichtenstein's defense of his work suggests how deep-seated the problem was:

The UAW leader's complicity with the auto industry's system of racially-coded employment came under attack, within the UAW itself, when the Trade Union Leadership Council burst on the scene late in the 1950s. Led by articulate blacks like Horace Sheffield and Willouby Abner, TULC successfully challenged Reuther's claim to speak as a principled advocate of black auto workers…. Once you know why Reuther fought TULC — and later the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement — a reader does not have to spend much time detailing the extent to which the top leadership of the UAW did not seek a vigorous enforcement of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Had Sheffield or Abner won a seat on the UAW executive board they would have inserted into the highest union councils the views and power of an independent insurgency within the UAW, and in the process challenged the politico-legal posture of Reuther and his caucus. This would have forced the UAW to confront the covert racists and stand-pat ethnic machine politicians which had become a mainstay of so much of the Reutherite UAW.

It's history, but history creates a long shadow. In 2005, Ta-Nehisi Coates, now a star at The Atlantic, visited the South Side as WalMart was making inroads there and in cities throughout the country. There he found this painful wound was still fresh:

Chicago is a union town. But in Mitts' ward–and among many poor blacks–some unions rank only a couple of notches above the Ku Klux Klan. Black leaders in Chicago have repeatedly charged that the building-trades unions, traditionally controlled by whites, are keeping a grip on jobs. While 37% of Chicago is black, only 10% of all new apprentices in the construction trades between 2000 and 2003 were black, according to the Chicago Tribune. The unions that most vociferously oppose Wal-Mart are not in the building trades but represent retail workers, such as the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), which has long welcomed blacks.

This also emphasizes the substantial differences between unions; not all have been impediments to minority employment. Currently, blacks and Hispanics are more likely to be unionized than whites, and the wage premium for unionization is greater for blacks and Hispanics than it is for whites (BLS data, 2007):

How'd that happen? Private-sector skilled-trade unions have been in decline, while public-sector unions have maintained consistent membership over the past couple decades. Shut out of skilled private-sector unions, blacks found reliable middle-class wages in skilled, unionized public-sector jobs—which have been hit hard by government cutbacks:

Though the precise number of African-Americans who have lost public-sector jobs nationally since 2009 is unclear, observers say the current situation in Chicago is typical. There, nearly two-thirds of 212 city employees facing layoffs are black, according to the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Union.

The central role played by government employment in black communities is hard to overstate. African-Americans in the public sector earn 25 percent more than other black workers, and the jobs have long been regarded as respectable, stable work for college graduates, allowing many to buy homes, send children to private colleges and achieve other markers of middle-class life that were otherwise closed to them.

But racial tensions with regards to skilled private-sector unions remain. In 2008, a couple weeks in advance of the election, the Washington Post's Harold Meyerson wrote a lengthy piece for the American Prospect about the AFL-CIO and its difficulties in rallying members around a black candidate:

Indeed, in a year that has been marked by a tsunami of volunteer activism — by one count, a mind-boggling 5 million Americans have volunteered for the Obama campaign nationally — the turnout by Ohio union members for labor's campaign has been notably smaller than in past elections, at least in certain parts of the state. "This year, it's been very difficult to get volunteers out," says Skeen, the Columbus-area [AFL-CIO] coordinator, "partly because of Barack at the top of the ticket. We've had big get-out-the-vote programs for the past four years, but this year, people are just burnt out. Phone bank workers and precinct walkers hear a lot of racist remarks. Some local leaders say they don't want to be involved because it may affect their own re-election. Leaders of the [building] trades have had a hard time getting out front of their members."

The effort has not been without success; outside the South, Obama is doing well among white working-class voters. But the effects are lingering: in labor tensions within developing neighborhoods, in the fracturing of the New Deal coalition; in the absence of a larger black middle class in northern cities; in the decline of skilled private-sector unions, which spent decades alienating a potential base. It's too simplistic to blame "unions" for black unemployment, but it's also too simplistic to boil Emanuel's statement down to that. From a historical perspective his specific statement was right, and the mayor, like the rest of us, has to grapple with living in the wake of that history.

Comments are closed.