Yesterday I did a quick run-through of a report by the State Budget Crisis Task Force (the brainchild of bureaucratic veterans Richard Ravitch and Paul Volcker) on Illinois's perilous budget problems. They intentionally focused on problems instead of solutions—understandable if a bit frustrating, as there's been plenty of discussion about the former and much less about the latter—but they do weave a few quiet, genteel hints in the theses nailed to the state's door.

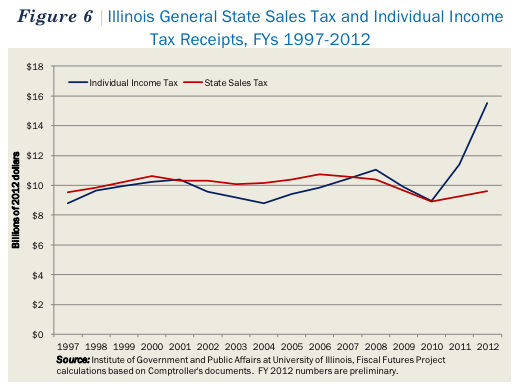

* The authors note that before the income tax was raised, tax revenues had been essentially stagnant for over a decade:

And the income tax hike gets phased out, so the take will plummet. What's the cause?

In Illinois, as in other states, stagnation of sales tax revenues is primarily due to two factors: the expansion of the service sector of the economy while few services are taxed; and the increase in Internet purchases which are not subject to the state sales tax.

They don't go so far as to make a specific recommendation, but it doesn't take much to read between the lines:

Compared to other states, Illinois taxes very few services. A 2007 survey found that out of 168 potentially taxable services, Illinois taxed only seventeen, compared to a national average of fifty-six. Only four states taxed fewer services than Illinois. At the same time, Illinois’ economy is more dependent on services than many other states, primarily due to the importance of service industries such as finance and insurance, professional services, and information. In 2011, COGFA estimated that if Illinois were to implement taxation of services (excluding business to business transactions) this could generate $4.0 to $8.5 billion in new revenues per year, although the amount that is politically feasible could be much lower.

In other words, basically the difference between current income-tax revenues and what they'll be when the hike is phased out.

* There's another way that the state's tax structure hasn't kept up with the evolution of the economy:

Because Illinois has a flat rate tax with a personal exemption of only $2,050 per capita, the system has a roughly proportional burden across different income groups. This lack of progressivity in the personal income tax system, combined with the nationwide trend toward rapid growth of income among high-income individuals, has meant that income tax revenue has grown somewhat more slowly in Illinois than in states with a progressive tax system.

They also point out that the flat tax makes the state's revenues less volatile, but one of the report's few explicit recommendations is an honest-to-goodness rainy-day fund that would cushion against revenue volatility. There's been a push for a progressive income tax for awhile now, not just out of fairness, but to keep up with the changing distribution of income. (Adam Doster wrote an excellent explainer for Progress Illinois in 2010.)

* Then there's the state's mess of local governments:

Crowding out of the state budget also threatens what meager fiscal oversight exists in Illinois. Local governments other than school districts are required to file financial reports with the comptroller, but that office does not have the necessary staff to review the reports, nor does it have the authority to force a local government to change its practices.

And we have a lot of local governments to not have fiscal oversight over. But there are barriers:

The Legislature didn't bite last year on Quinn's call to cut the number of school districts. It did, though, create the Classrooms First Commission, charged with studying the issue. The commission, chaired by Lt. Gov. Sheila Simon, poured some cold water on consolidation when it reported this month that cutting the number of districts by nearly half would … cost the state $3.7 billion.

The commission points to financial incentives that the state promises to merging districts — mainly additional money for teachers' salaries. For instance, when high school and elementary districts merge, the state provides money to bring lower-paid teachers up to the level of higher-paid teachers. (High school teachers generally have a higher pay scale.) There's also a flat $4,000 payment to the district for every teacher, administrator and other professional staffer.

Beyond that, the report's recommendations are mostly a "toolkit": budget practices like an omnibus spending bill, pricing the costs of legislation, multi-year budget forecasting, and other best practices designed to make the state government better at budgeting, and thus more likely to spend, tax, and save more wisely, but they're just tools, not recommendations for what parts of the budget they should saw and hammer off.