The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning is pushing an ambitious congestion-pricing plan for Chicago interstates, and from the perspective of Jon Hilkevitch's latest, it sounds like they're expecting quick implementation. Here's why:

The Illinois Tollway's 87.5 percent increase in tolls this year "did nothing to encourage smart economizing on driving," Schwieterman said. "I think people are starting to understand we have no realistic chance of building our way out of this mess. It's just not mathematically possible that transit alone can bail us out of suburban gridlock."

This is the general principle of roadbuilding, and it's surprisingly robust: more roads means more cars, not less congestion. And public transportation doesn't put a dent in it:

[O]ur data suggests a ‘fundamental law of road congestion’ where the extension of most major roads is met with a proportional increase in traffic. Not only do we provide direct evidence for this law, but also show find evidence that three implications of this law; near flat demand curve for VKT [vehicle kilometers traveled], convergence of traffic levels, and no effect of public transit on traffic levels.

The authors estimate that, because of increased driving and increased population, increased driving simply outpaces increased roadbuilding: "To begin, consider a 10% increase in the interstate network of an average MSA around 2000. Using our preferred estimate from column 5 of table 4, this increase causes a 10.4% increase in VKT on the interstates of our hypothetical city." I like Felix Salmon's metaphor: "traffic is like water — it wants to find its own level, which tends, in cities, to be maximum capacity."

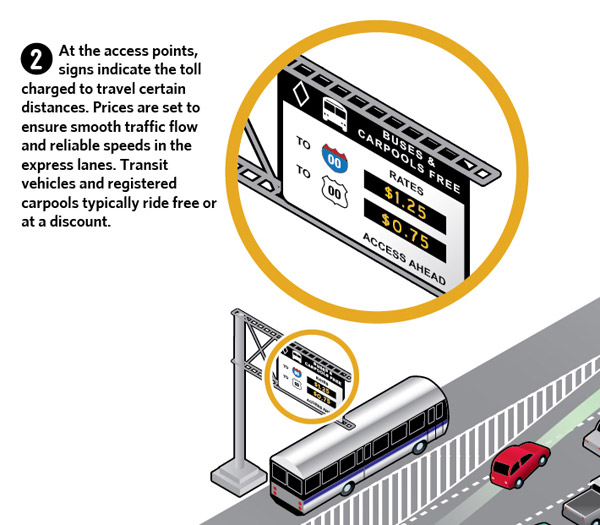

Big toll hikes don't fix it. Building more lanes and more highways doesn't fix it. That's where variable pricing comes in. The express lanes provide for faster traffic, but to keep traffic moving fast, the fee has to adapt to levels of congestion. And it has to be able to get high enough that some people won't choose to pay the charge: "In Singapore, they set the amount of traffic they want, and then dial up the congestion charge until they get it."

And people don't like that: watching other people zip by them, or paying to drive on roads. And since it changes, it's another thing to have to pay attention to, unlike tolls. It's part of the broader benefits of congestion pricing, making the costs of roads explicit, but it adds more decision-making to the commute.

Or maybe that's part of the fun: it turns commuting into arbitrage. Here's one way to look at it:

According to Small and Verhoef (2007), the standard approach in transportation studies is to value the time cost of commuting at half the wage. We follow this approach. As an illustration and taking median MSA values, 0.023 hour per kilometer valued at a 2000 hourly wage of $ 20.20 adjusted by a factor of 50% (and inflation) implies a time cost of $ 0.26 per km in 2008 dollar.

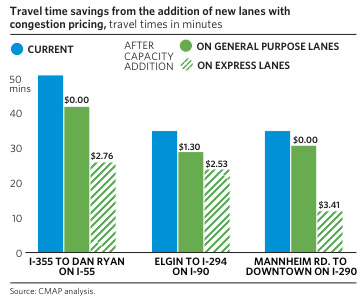

Now compare that to CMAP's estimated travel-time savings:

Let's assume you save 15 minutes on Mannheim. That's one-quarter hour, at $3.41. If you make $20 an hour, and value your commute at $10 an hour, it's not worth paying $3.41. It's close to worth it on I-55. But if you make $40 an hour, it's (theoretically) worth it. (I look forward to traffic reporters trying to integrate variable congestion pricing into their reports: "40 minutes to the Dan Ryan from 355 in the free lanes, 25 in the express lanes, which are running at eleven cents a mile right now.")

Is it unfair (PDF)? Sort of—the more you make, the more affordable it is, which is frustrating if you don't make much. But it also shaves time off the free lanes, which building more roads has never done.