While off dealing with my own potential future Chicago Public Schools student, Steve Bogira published a Reader cover story profiling three families who moved to the suburbs to get their kids out of CPS. It's a good piece in its familiarity; it should strike a chord in anyone who's had to deal with this as a student, which I have, and as a parent, which I'll have to.

The one most familiar to me was the Stapp family, whose complaints about their CPS educations reminded me of complaints my friends had in rural Virginia public schools, save for the gang fights:

Johnny's from Austin, on the west side. He was raised by his mother; his father was mostly in jail. His mother first sent Johnny and his two brothers to a small Christian school. The school closed after Johnny finished seventh grade. Then he went to the neighborhood public school, May elementary. That was a "rude awakening," he says. "In the private school they tell you, 'We're teaching you to be two grades ahead.' Once you get to the public school, you realize they were telling the truth. I was extremely bored."

[snip]

Johnny's mother and his grandmother, a math teacher at Austin, pushed him academically. But he felt unchallenged. "I definitely wasn't the smartest kid," he says. "There were a lot of intelligent kids who were just sitting there bored in class. You develop the habit of, 'I don't need to really study because I've got this down. I don't need to do the homework, I can just take the test.'"

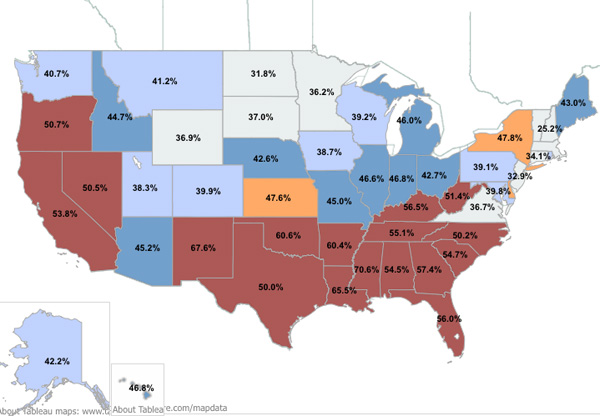

It's simply a difficult task for schools and their teachers—push the smartest or hardest-working students too hard, and you risk losing the most at-risk students; attend to the most at-risk students too much, and you risk losing the best students. Even if a parent and child can set aside the grinding race for elite schools, it's a lot of time for a student to spend in boredom. And schools lose a lot of middle-class students, especially urban schools. The Southern Education Foundation recently released a report documenting the increasing percentage of low-income students in the nation's public schools; here's the percentage, by state. Illinois is pretty average, as are the Northeast and Midwestern states with big cities.

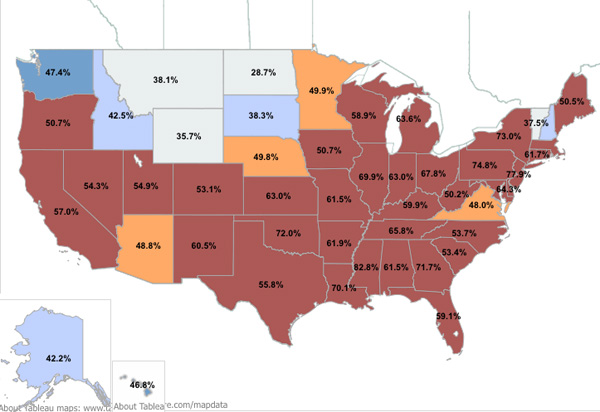

Now here are the percentages for urban schools with low-income students. Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York rise to the top.

And it's not just families leaving the schools; it's families leaving the city, for one simple reason: "The taxes are higher here than in Chicago, she says. 'Taxes are insane, but it's cheaper than having to pay for private school.'" "Insane" is relative, but it is true that Chicago's residential property taxes are lower than most of its suburbs, even extremely wealthy ones like Winnetka and Wilmette.

Philadelphia has been controversially and aggressively reforming its financially struggling school system in ways similar to CPS and for similar reasons, with an eye towards growing its middle- and upper-middle-class population. Chicago's well-off center-city population is growing, but the fear down the line is that there will be another exodus when those kids hit school age, for the reason the families explained to Bogira.

And Philadelphia actually tried very explicitly to market some of its schools to that demographic cities are trying to lock down for life. Maia Bloomfield Cucchiara, an assistant prof of urban education at Temple, studied what happened. In some ways, it worked; in others, it reinforced existing problems.

The marketing worked: According to my analysis of School District of Philadelphia data, by 2009 the number of Center City children enrolled in first grade in the three most desirable public schools had increased by 60 percent, from 111 to 177. Through fundraising and the activation of social and professional networks, these new families helped bring resources to the schools, including new playgrounds, libraries, and arts programs. But these Center City children weren’t taking empty slots. When they enrolled, they left fewer spots for low-income students from North and West Philadelphia, who had for years used those schools to escape failing ones in their neighborhoods. During this period, the number of first graders in Center City schools from outside the neighborhood decreased by 42 percent, from 64 to 37. Not surprisingly, this shift had racial dimensions: The percentage of white students in these schools in the early grades increased by 30 percent, and the percentage of African American students decreased a corresponding 29 percent.

[snip]

[R]esearch by Northeastern University sociologist Shelley Kimelberg suggests that, because middle-class parents tend to “cluster” in certain schools, their actions have the potential to increase racial segregation in Boston public schools. In her research on school reform in Chicago, University of Illinois professor Pauline Lipman has found large and growing disparities between schools serving poor students and those serving the more advantaged.

Cucchiara suggests other alternatives, such as regional coordination between city and suburb instead of a pitched battle that recreates such disparities within the city limits. Pulling suburban parents back to the city can be good for the tax base, which isn't unimportant; but in and of itself, it's unlikely to improve the schools that need the most help.