Photo: Library of Congress

Just before midnight on Sunday, October 8, 1871, my great-great-great-great grandfather Roswell B. Mason was roused from his slumber at his home on Michigan Avenue. According to a biography of Mason published by the Chicago Historical Society, the man galloped up to the Masons’ house and called up to the sleeping man’s window, “Mayor! Come give orders to save the city!”

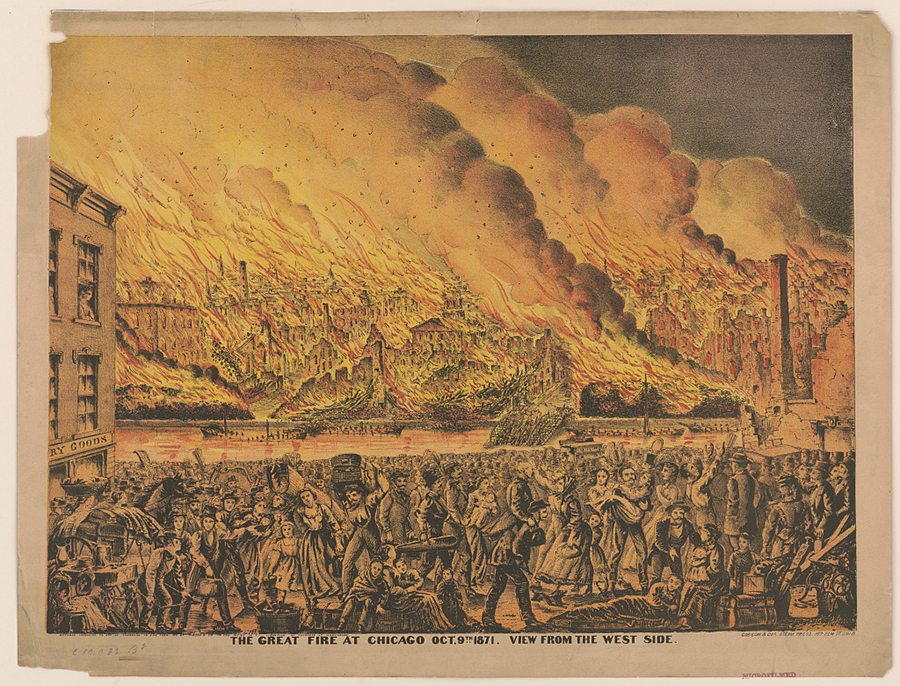

A fire was spreading fast through the streets of Chicago—the second one in less than 24 hours. The first began at a planing mill, which stood between Jackson and Van Buren on Canal Street, at midnight the day before. It raged for nearly 16 hours, and when the flames were finally quelled, they had devoured four city blocks and exhausted nearly all the resources of the Chicago Fire Department. The entire department had been called out for the job. After nearly a full day of battle, the firemen stumbled home to their wives and children covered in soot and sweat, in desperate need of a good night’s sleep. But the fire wasn’t finished. Just hours later, around nine-o’clock on Sunday, these soldiers of the flame were once again shaken awake, and this time, the fire won the war.

There is a considerable amount of mythology around the Great Chicago Fire. Maybe, like the old stories say, Mrs. O’Leary left a lantern in her little barn on DeKoven Street. Maybe her cow knocked it over as it settled into the hay for the evening. Maybe one Peg Leg Sullivan saw the flames from across the street and hobbled over on his wooden foot to save the animals trapped inside the barn. The city of Chicago officially exonerated Mrs. O’Leary in 1997, 102 years after her death, but the legend still remains.

However the fire started, it spread quickly, happily feasting on wooden houses and storefronts, fueled by the crispy brown leaves littering the cracked, drought-ridden ground. The firemen fought gallantly, but after the previous night’s efforts, few of them were up to the job. To make matters worse, the mill fire had destroyed much of the equipment needed to combat this new blaze, including a few of the department’s newly acquired steam-pump fire engines, which were pulled by horses. The exhausted firemen had to abandon the fight at Chicago and Michigan Avenues, when it became clear that continuing the battle would mean certain death.

Mason was in his final months as mayor, elected by a city with a growing revulsion to the rampant corruption and immorality plaguing its streets. It was, according to Herman Kogan and Lloyd Wendt in their book Chicago, a Pictorial History, “a time of easy morals and easy money”; gambling saloons, brothels, and crooked councilmen were popping up everywhere. But Mason was well liked by both his constituents and the press. He was generally thought of as a moral and dedicated family man, whom the Chicago Tribune dubbed “an honest man presiding over a den of thieves.”

In the 1870s, the Republican Party was still the party of Lincoln and liberal idealism. While Republican in his views, Mason ran and won under the Citizens’ Ticket, making him the last sitting Chicago mayor who was neither a Republican nor a Democrat.

Even people who disagreed with Mason’s policies seemed to respect him as a leader. I spent hours poring over old newspaper articles from before and after the 1869 election, searching for even a hint of the kind of divisive political opinion piece that dominates our current 24-hour news cycle. The closest I got was in an 1870 Chicago Tribune article detailing Mason’s plan to reform the city budget: “The mayor suggests that the $3,000,000 expended on the canal improvement will be returned to the city,” wrote the unnamed reporter. “We regret to say that the prospect is not a very flattering one… we fear it will prove a total failure.”

Despite these cutting remarks, the author closed with this: “While we cannot agree with all that he says about the canal improvement, we cheerfully bear our testimony to his fidelity to the important interests committed to him.”

How times have changed.

I grew up hearing the story of Mason’s life over and over, as did my mother and my aunts before me, and my grandmother before them. In our family, his name is sacred, always uttered in the same breath as his title and place in history: “Roswell B. Mason, mayor of Chicago during the Great Chicago Fire.” So perhaps we had donned rose-colored glasses about our ancestry, but by all accounts that I could find, he was a kind and gentle man. An attentive and present father in a time when little was expected of fathers. A funny and supportive friend, a faithful husband. A level-headed leader who never pushed his personal beliefs on his constituents, who commanded the respect of even his political rivals.

Before the fire in 1871, before he took office in 1869, before he was appointed chief railroad engineer of the Illinois Central Railroad, before he decided to add the “B” in between his first and last names as a symbol of authority, Roswell Mason was a sickly child. A biographical record of his life written by his son, Henry B. Mason, tells that Roswell’s early life was plagued with illness.

His father was a well-to-do farmer and contractor, and though his health was poor, Roswell spent his summers working on the farm. In 1821, the 17-year-old Roswell accompanied his father on a canal contracting job in Albany. All summer, the teenager helped his father haul stone to build a lock near the Erie Canal, and as a result he landed a job on a canal engineering team. He quickly rose up through the ranks, eventually attending an elite engineering school in Utica and returning to a job as a railroad engineer.

According to family biographers, in 1825, Roswell was hard at work as the principal assistant engineer on the Morris Canal, near the town of Parsippany, New York. Often he and a few other young engineers would spend the night at the home of Royal Hopkins, a Parsippany contractor with a beautiful daughter who caught Roswell’s eye.

Harriet Lavinia Hopkins met the young engineer during a dinner at her father’s house. She later told her children her first impressions of Roswell left her thinking: “You are a very nice young man, but I shouldn’t like to marry you,” perhaps because the whole romance was too convenient for him. Her house was on the road he traveled on his way to and from work, and family lore says she often lamented how easily he won her.

As her son, Henry B. Mason, recalled in his speech at the couple’s 50th anniversary party in 1881: “She insists that he secured her with too little trouble, but adds that she has given him trouble enough since that time.”

By 1865, the Masons had settled in Chicago. That year, Roswell was one of the four top engineers in charge of cleaning up the Chicago River. They deepened the Illinois and Michigan Canal, established pumping works at Bridgeport and lowered the summit of the canal to reverse the river so it flowed into the Illinois River. Today’s beachgoers can thank Mason for their leisurely, cholera-free swims in Lake Michigan.

Four years after the river cleanup, in 1869, Mason was elected mayor of Chicago.

At the time of the fire, Chicago was young—a fledgling city in a fledgling country. Detailed histories of the area don't go back very far, but it's believed that members of the Hopewell Tradition, an ancient network of Native American societies, lived on Lake Michigan starting from around 200 BC. The Hopewell culture was made up of farmers, fishermen, traders, and artists. They buried their dead in elaborately constructed mounds, outfitting the corpses with the fruits of their expansive trade network: shell cups from the Gulf of Mexico, handmade freshwater pearl necklaces from the Mississippi River Valley. Some of these mounds still stand today in southwestern Illinois, monuments to an ancient culture discounted and erased by European historians.

White settlers began to flock to the area in the late 18th century. Looking at maps from the time, you can tell there there is no plan at first; houses spring up haphazardly with no grid to guide the construction, but that soon changes. Streets are arranged in straight lines around the river, schools are built, children are born and grow up to have children of their own. Brick by brick, the once untamed wilderness surrounding the river is a small town of 200 in 1831. A moment later, that small town is now home to 4,170 people who are granted a city charter and elect their first mayor, William B. Ogden, in 1837. When Mason was elected less than 40 years later, the city’s population had grown to nearly 300,000. It was busy, it was bustling, and it was made mostly of wood.

The night of the fire, after hearing the horseman’s call to action through his open window, Mason jumped on his own horse and raced to his office at City Hall, above the courthouse on the southwest corner of Clark and Randolph. By the time he arrived, the relentless flames were just starting to lick the sides of the building. Despite the danger, he ran inside and began firing off desperate telegrams to nearby cities like Milwaukee and Detroit:

Before morning one hundred thousand people will be without food or shelter. Can you help us?

Soon after Mason’s arrival, at around one-o’clock in the morning, a strong, hot wind carried embers from the surrounding chaos to the top of the courthouse’s imposing wooden cupola. It burst into flames, sending a wave of thick black smoke down into the halls surrounding the mayor’s office and the courthouse jail that lay beneath City Hall.

According to eyewitness reports, the inmates began screaming for help. They banged frantically on the bars which held them prisoner as smoke filled their holding cells. In response to their cries, several people on the street began trying to free the prisoners by breaking a hole in the wall of the jail, but their rescue attempt was thwarted by a county official, who coldly informed them that only the mayor could order the release of these men.

Upon hearing the plight of the prisoners trapped beneath him, Mason grabbed a sheet of Chicago Police stationary and, using a pencil, hastily scrawled out a proclamation:

Release all prisoners from jail at once, keeping them in custody if possible.

On his orders, a flock of frantic men were let out into the smoldering city streets. Although officers tried to keep the more dangerous criminals in custody, most of them escaped into the night. Family legend says Mason’s son tried to stop a burly man who was being held on a murder charge as he attempted to escape justice. But the mayor’s son was small in comparison to the prisoner, and he was knocked down with just one punch. The man ran off into the flames, never to be seen again.

Mason stayed at his office until just before the building’s bell tower came crumbling down in the early hours of the morning. Exhausted, disheartened, and covered head to toe in soot, he made his way back home through the fire. On his way, he is said to have ordered the destruction of buildings of Wabash Avenue and Harrison Street, to prevent the fire from venturing any farther south or east. When he finally arrived at his house at 4:30 a.m., his wife Harriet at first refused to let him in the door. His face and clothes were black with soot, and his hair and beard were disheveled and caked with sweat and dirt; Harriet looked upon her husband without recognition, seeing only a wandering vagrant. After a few minutes of cautious conversation, she realized her mistake and welcomed her husband back into their home, tearfully enfolding him in her arms.

“THE GREAT CALAMITY OF THE AGE!” screamed the headline on the front page of the Chicago Evening Journal-Extra on Monday, October 9, 1871. “The scene of ruin and devastation is beyond the power of words to describe. Never, in the history of the world, has such a scene of extended, terrible and complete destruction been recorded; and never has a more frightful scene of panic distress and horror been witnessed among a helpless, sorrowing and suffering population.”

At the time these words were written, around 1 p.m. on Monday afternoon, the city was still burning. Finally, around midnight on Tuesday morning, a soft but persistent rain began to fall, the first precipitation in three long months. It started as a light sprinkling, but soon erupted into a full storm. Drop after drop, the water crashed down onto the flames, hitting the embers that littered the singed ground with a hiss before evaporating into puffs of white steam.

The Chicago History Museum has hundreds of letters written just after the fire by Chicagoans who survived the blaze. These letters include devastating descriptions of charred houses, lamentations for dead and missing friends and loved ones, and sad musings on the future of the ruined city. But nearly every one mentions the rain. A cleansing salvation. The rain poured on the smoldering city for nearly a full day. Try as they might, the flames could not survive the downpour, and soon the charred city streets were slick and wet, scattered with the remains of the homes, businesses and lives taken so suddenly by the fire.

Mason’s efforts to save the city in the aftermath of the fire were nearly universally lauded in all the press clippings I could find from the era. He issued executive orders establishing the price of bread, banning smoking, and forbidding wagon drivers to charge more than their normal rates.

Family legend tells that after Illinois Governor John Palmer, a political rival of Mason’s, ignored the mayor’s requests to bring the National Guard to Chicago, Mason took matters into his own hands. He put the city under martial law, and issued a proclamation putting his friend, commanding general and Civil War hero Philip Sheridan, in charge. Sheridan brought in troops from the nearest military base to keep the peace in the city, and after several days with no serious disturbances, Mason lifted the martial law.

Two days after the fire, Mason issued a proclamation promising to restore order in the city, and in the following days, weeks, and months, help arrived in droves. Men and money from surrounding cities poured in to assist in the cleanup and reconstruction. When corrupt members of City Council tried to gain control of this relief money, Mason stepped in to prevent them from using these funds for their own personal gain. He turned over all contributions to the Chicago Relief and Aid Society, effectively halting the impending theft and jump-starting reconstruction projects.

For many Chicago residents, the idea that the city could survive this disaster was unfathomable. Lawyer Jonas Hutchinson, whose home and office at 86 Washington Street were burned to the ground, wrote a letter to his mother on October 9th expressing this sentiment:

I cannot see any way to get along here. Thirty years of prosperity cannot restore us. It looks as though I must leave here & what to do I do not know.

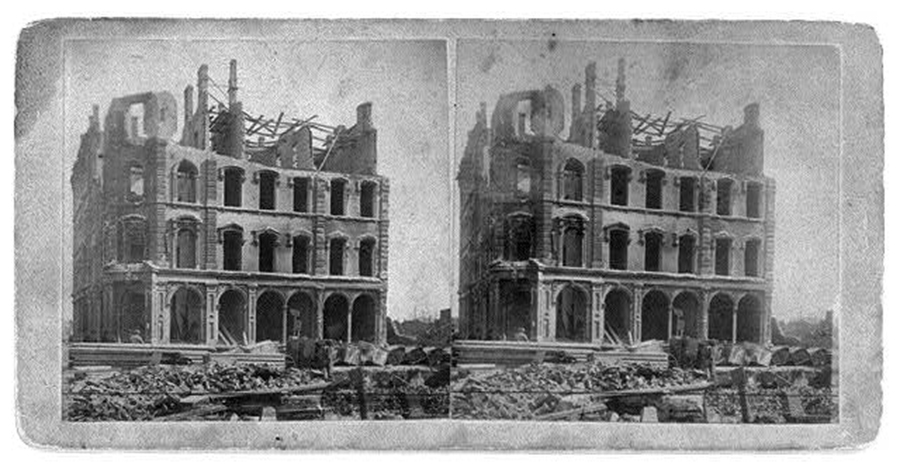

Yet somehow, within a matter of years, a new, imposing city of stone and brick rose from the ashes of its wooden predecessor. According to U.S. Census data, in the decades prior, Chicago’s population was growing exponentially every ten years. The fire did nothing to curb this trend.

By 1880, the city boasted a population of over 500,000, a rebuilt downtown, and ever-expanding city limits. Hutchinson’s pessimistic predictions were proven wrong once and for all in 1893, when, just 22 years after the fire, hundreds of thousands of people from around the world poured into the city to take part in the Chicago World’s Fair.

Hutchinson, surrounded in 1871 by the still-burning wreckage of his life, could not have known how quickly Chicago would bounce back. But the citizens refused to let their city crumble into the void of history.

On the first anniversary of the fire, the Chicago-based real-estate magazine Land Owner published a collection of photographs, lithographs, and drawings showcasing the impressive progress made in just a year.

“Our citizens have not been satisfied to simply replace the old city,” read a written piece alongside the pictures. “It has been their ambition to build it more beautiful and attractive than it was before it fell a victim to the resistless avalanche of fire.”

Mason’s term as mayor expired just two months after the fire. He was implored by many to run for re-election, but according to my cousin Manly Mumford’s self-published biographical booklet, The Old Family Fire, Mason “threw up his hands in horror over the prospect of serving again.” He was tired, and was perhaps spurred by the devastation he witnessed during the fire to spend more time with his family.

Mason died on January 1, 1892, at the ripe old age of 86, but his legacy lives on. The city he loved and led grows and changes with time, having risen to greatness from nothing—not once, but twice.

Comments are closed.