The North Side as we know it today — affluent, educated, white — began to develop in Lincoln Park in the 1940s and '50s. The catalyst? Middle-class rehabbers who moved into what was then a low-income neighborhood and began pushing for urban renewal.

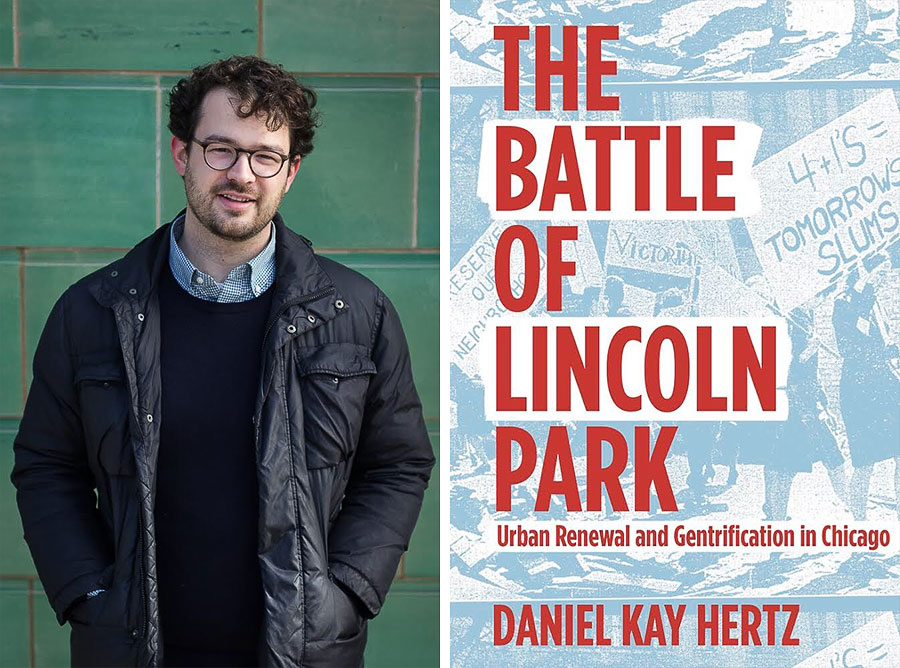

In his new book, The Battle of Lincoln Park: Urban Renewal and Gentrification in Chicago, Daniel Kay Hertz tells the story of that campaign. It began with the foundation of neighborhood improvement associations, and culminated in violent clashes with soon-to-be-displaced Puerto Ricans in the late 1960s.

Hertz, 31, is a Chicago native who grew up mostly in Albany Park, and attended Whitney Young High School before graduating from Evanston Township High School and earning a degree in government from Harvard College. This Friday, he'll discuss and sign copies of his book at 7 p.m. at Women & Children First bookstore (5233 North Clark Street).

We met up for an interview at City Grounds Coffee — in the heart of Lincoln Park.

Why write about Lincoln Park? What does that neighborhood represent in Chicago?

Lincoln Park is the poster child of wealthy, white North Side neighborhoods — so wealthy that I don’t think most people think of it as having gentrified at all. It’s just sort of always been that way.

But I didn’t choose Lincoln Park for those connotations. It seemed to be the first place that gentrification really happened in Chicago, in the way that we think of it now.

Why did gentrification in Chicago start in Lincoln Park?

It’s on the park and the lake and it’s very close to downtown. Honestly, it’s the Gold Coast. [Lincoln Park's] Old Town Triangle is right around the corner from the Gold Coast. People who would have moved into the Gold Coast if they could afford it instead moved to the Old Town Triangle.

People may be surprised to find out that Lincoln Park was once one of the city’s poorer neighborhoods.

It was in the bottom quarter of neighborhoods in per capita income in 1950 and 1960. Median income in Lincoln Park didn’t get higher than median income in the city as a whole until 1980.

The average household income is now $94,000, and 82 percent have a college degree.

Now I think it’s almost double the city’s average. The proportion with a college degree is almost the most telling. In the city as a whole it’s a third, so that’s pretty skewed.

So why was Lincoln Park so down at the heels in the ’50s and ’60s?

For the same reason as a lot of core urban neighborhoods: Newer buildings had been built further out in the city and in the suburbs. We think of suburbanization and white flight as taking place during World War II and after. But even in the teens and twenties, when Chicago was gaining population, the inner rings of development that included Lincoln Park were losing hundreds of thousands of people.

“Gentrification” is often used as a dirty word, but is it inherently bad? In the ’70s and ’80s, it seems like not many people who could afford the suburbs wanted to live in the city. What’s wrong with having people of means coming back and wanting to live in the city?

I’m hoping that the book gets out of that trap of saying, “You have to choose either increasing disinvestment and poverty or gentrification.” The way that Lincoln Park and the North Side avoided disinvestment was by creating this “green zone." Within this zone, which started as the Gold Coast and the Old Town Triangle, city services would be up to par, the schools and streetlights would be taken care of, and outside that zone, they wouldn't be. That created this dynamic where middle class people moved back to the city and paid as much as they could to make sure they were inside that green zone.

What was the Battle of Lincoln Park, and who ultimately won?

In some sense, it’s the whole story of these middle-class rehabbers coming in and changing the neighborhood.

But I think the "battle" part happens starting in 1968, when a Puerto Rican street gang called the Young Lords is re-founded as a radical political organization based on the Black Panther Party. They made opposing urban renewal one of their top issues. The Halsted and Armitage area was the epicenter of the Puerto Rican population.

Prior to the Young Lords, there had been organized opposition, but it had been more genteel people — members of the clergy who staged pickets and letter-writing campaigns. The Young Lords showed up to these meetings and threw chairs. They were physically disruptive in a much more in-your-face way, and that changed the tenor of how the middle-class movement thought of their opposition. It radicalized a lot of the more conservative members as well.

You end up with real violence. Multiple members who were allies of the Young Lords were killed in 1969. The pastor of the church that they had made their headquarters was murdered.

When did the Latino population start to disappear from Lincoln Park?

It was substantially diminished by the early to mid–’70s. People moved either up to Lake View, or to Humboldt Park and Wicker Park. There was a neighborhood library [in Lincoln Park] that had opened a Spanish section, and by 1973, they shut it down because the constituents were gone.

Certainly, those people lost the battle. But many of the more idealistic rehabbers lost the battle, too. Many of the people who were leaders in the ’50s and ’60s are incredibly disillusioned about what they thought they were building.

You talk about how Lincoln Park has a symbolic meaning in Chicago. Is this where the North Side as we know it today began?

Definitely. The pattern of gentrification that was established in the ’40s and ’50s in the Old Town Triangle is what has repeated over and over again, now out in Humboldt Park and Avondale and Pilsen.

Are there neighborhoods that have attracted rehabbers and wealthy homeowners but remained integrated by race and income?

It feels too cynical to just say no. I live in Edgewater, east of Broadway. It is a mixed income neighborhood that certainly has plenty of professional-class people. Part of that is there is a very large concentration of low-income housing in that area, in Uptown. McKinley Park comes to mind, where there are plenty of middle-class homeowners, but it’s not directly adjacent to this green zone that now encompasses Wicker Park and Ukrainian Village. I think because it’s not directly adjacent it doesn’t face these same pressures.

What’s your recommendation for bringing middle-class homeowners into a neighborhood without displacement?

Providing a lot of low-income housing and moderate-income housing that’s not tied to the market is helpful.

Another thing is breaking this dynamic, which existed in the ’60s and still exists now, where somebody comes from the suburbs or from Denver or wherever, to the city, and they see neighborhoods where quality of life is really, really high, and they see neighborhoods where quality of life is not high — because schools aren’t taken care of, public safety is an issue, and all these other things — and they’re willing to pay a lot of money to be on the winning side of that divide. Investing in neighborhoods outside of the zone of affluence — both for the people who already live there, and so people who move here aren't deciding that they’re going to bid up prices and push people out of areas close to the quote-unquote desirable neighborhoods.