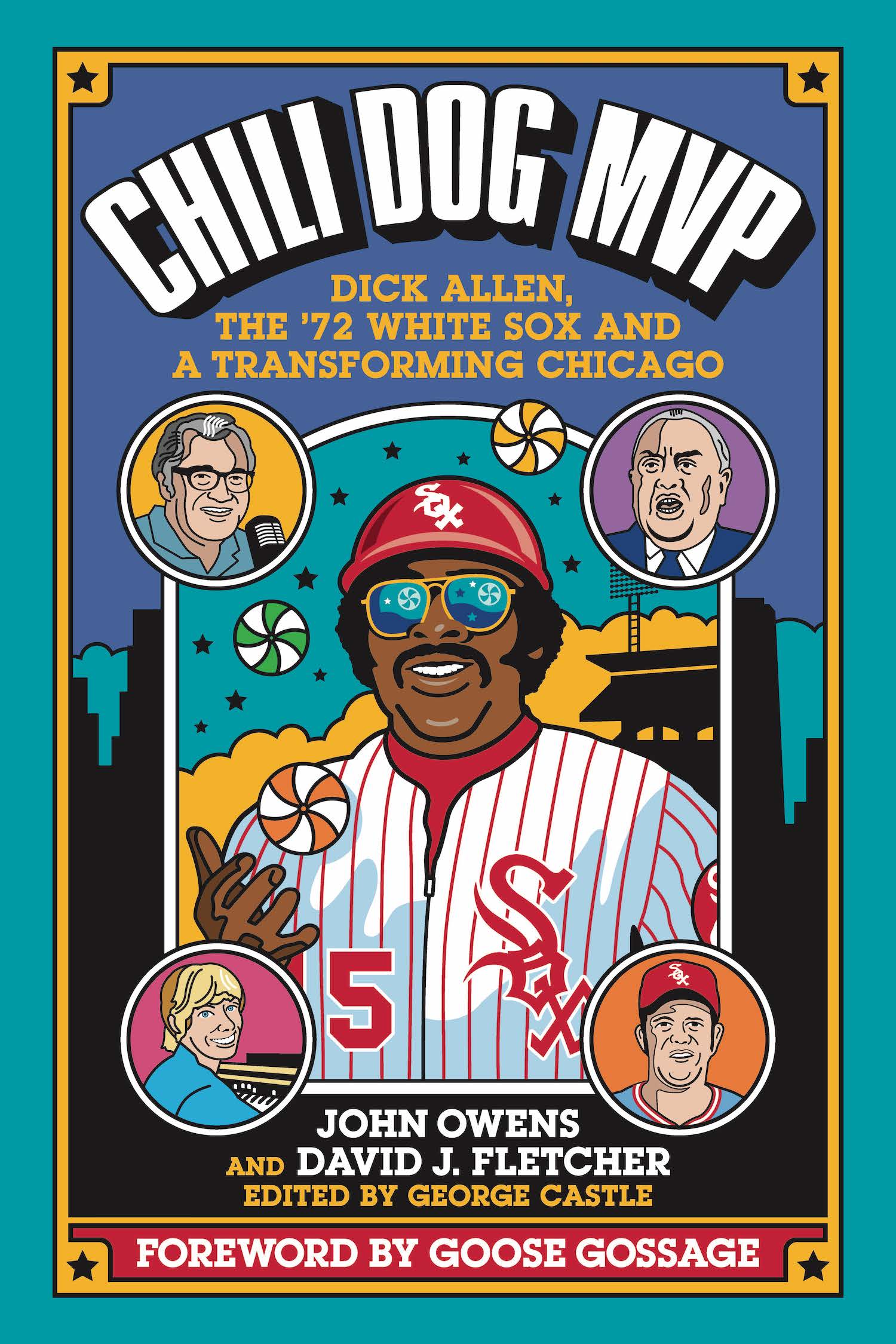

Dick Allen kept the White Sox in Chicago. That’s the argument authors John Owens and David J. Fletcher make in their new book, Chili Dog MVP: Dick Allen, the ’72 White Sox and a Transforming Chicago. By the late 1960s, the Sox already had one foot out of the city: they were playing 10 games a year in Milwaukee, and Bud Selig had made an offer to buy the team and move them 90 miles north permanently. The Sox acquired Allen in a trade from the Dodgers before the 1972 season, offering him a $140,000 a year contract — a quarter of their payroll. Allen rewarded his new team with an MVP season that renewed interest in baseball on the South Side. This month, Allen came up one vote short of election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame by the Golden Era Committee. That’s an overdue honor, say the authors.

What was the state of the Sox and the South Side in the early ’70s? And how did the state of the neighborhood affect the team?

Owens: The state of the Sox in the early ’70s — we’re talking like ’69, ’70, ’71 — was bleak. But the neighborhood only was part of the story. It was the story of how the team had been managed over the years by specifically [team owners] the Allyns — Art Allyn, especially. There were issues with media deals. He left WGN in 1967 and moved to a UHF station, WFLD. That hurt the exposure. The neighborhood, after 1968, Martin Luther King’s assassination, that certainly didn’t help, especially with perception of whether or not it was safe to come to the ballpark, although there were no incidents by the park. But, you know, it was a time when there was a lot of civil unrest in 1968. So that definitely played a role. But it was only part of it.

At that time, were the Sox in danger of leaving Chicago?

Fletcher: They were, definitely. Bud Selig, he actually bought the White Sox in September of 1969. He had a handshake deal for $13 million with Art [Allyn] to buy the Sox. He didn’t tell his brother who was half owner. And that’s kind of the story we tell is about John Allyn, the quiet owner, who saved what he believed was an important civic institution for Chicago, and kept the team in Chicago, plus also at Comiskey Park. His brother was trying to get this stadium by Dearborn Station. He is really an unsung hero. We really bring him to life, what he did, and he took the big risk of the payroll of Dick Allen, which was a quarter of the payroll.

So Dick Allen, what’s the importance of him and ultimately turning things around for the White Sox? Do you think he played a role in keeping the team in Chicago?

Owens: He definitely did, because he energized the fan base and brought the fan base back. They only drew for 475,000 in ’70. Dick was a superstar. He was arguably the best player in baseball at that time. The stats prove it. If you look at sabermetrics and modern stats, from 1964 to 1974, there was no better player in baseball. He was a gate attraction because of who he was. He was an iconoclast, he was portrayed as a rebel — and he was for baseball, because he knew his self-worth. He bargained for his salary. Held out for what he was worth every year. So he was resented for that and for other things. But he was Michael Jordan in Chicago before Michael Jordan.

How many did they draw the first year he played?

Fletcher: The first year they played, over 1.2 million. Double the attendance. The White Sox gained 70 wins from 1970 to 1972, and they would have won the American League West if Bill Melton hadn’t gotten injured.

How did Allen bond with the fan base? What was his impact?

Owens: He was a great five-tool player, so he was appointment viewing. You had to be in your seat when he was at bat, because something good was going to happen, something that you’ve never seen. Yeah, he’s a normal-sized man. He was only like 5’11”, maybe 180, 190, but he swung a 40-ounce bat, and he was just a true threat. In addition to his talent is that he was the epitome of cool. I was 7 years old when he was traded to the Sox in ’72, so as a Black child growing up on the South Side, he especially had significance for me, because he was so cool. He dressed like Superfly.

Fletcher: It energized the fan base, especially the mystery because he held out in spring training. And then the first game out in Kansas City was on April 15, the anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut, he hits a frickin’ home run in the top of the ninth against the Royals. Unfortunately, they lost in extra innings. In the beginning, the White Sox had a terrific home record. Comiskey Park was the place to be. It just brought energy and hope to the fans. He also had a great surrounding cast. He was the star attraction, but Carlos May, he was the second leading hitter on the team that year. He almost won the American batting crown against Rod Carew. You had Bill Melton, Wilbur Wood, Terry Forster, you know, “the fat tub of goo”?

But it’s not just a baseball book. It’s a book about Chicago and about plantation politics and Jesse Jackson and what happened in the aftermath of the Fred Hampton murder, what changed in Chicago, and we really weave that in the story about the Crosstown Freeway, the Democratic Convention in ’72, just the changing of the guard. That’s what makes it a Chicago story. Dick came out of nowhere. We needed a hero like him to energize the fan base. Suddenly, the Sox were relevant. People were coming to Comiskey Park. They had a young, exciting team. They almost won it in ’72. They started out great in ’73. But unfortunately, Dick broke his leg in June of 1973, and he never really recovered from that injury.

He came one vote short of election to the Hall of Fame this year. So is he going to get in, and why does he deserve to be there?

Owens: He definitely deserves to be in, because as I mentioned, between 1964 and 1974, no one — save maybe Henry Aaron — surpassed him as an offensive threat. His [Wins Above Replacement] was something like 58 for his career, which is higher than the WAR of any other player who was accepted into the Hall of Fame: higher than Tony Oliva, higher than Minnie Minoso, higher than Jim Kaat. He was just a tremendous player.

Why is it taking him so long to get in?

Owens: It’s a combination of things. He was on the baseball writers’ ballot until ’96, and I think the highest vote he got was 18%. He was always considered by the media to be a malcontent, and I think that hurt him. Now, with the Golden Era, you’ve got so many other deserving names that weren’t as controversial as Dick and they get precedence over Dick because of that reputation.

Explain the Chili Dog MVP title.

Owens: Chili Dog MVP refers to a game on June 4, 1972. Dick had played every game up to that point. June 4 was a doubleheader with the hated Yankees. That was always the toughest ticket in town when they came to town to play the Sox, and then this day it was record-breaking attendance with 51,000 people. It was Bat Day. Dick played the first game, and [manager] Chuck Tanner decided to sit him out for the second game because he had played the entire season. As it turns out, the Sox were down 4-2 in the bottom of the ninth, and Chuck Tanner decided, “I need to go pinch hit in this inning.” Dick was in the clubhouse throughout the game. He was in the whirlpool for a while and then he got out and was sitting by his locker eating a chili dog. So he pulled on his jersey, spilled some chili dog juice on his jersey, ran out and proceeded — with two men on base — to hit a line drive shot into the left field stands and win the game for the White Sox. It was a symbolic moment for the season; it was probably one of the most exciting moments of the season and then showed how much Dick had grabbed the attention of the fans and energized the fan base and was becoming the dominating sports figure in Chicago.