Doug Oberhelmen, Caterpillar CEO, on Friday:

"We cannot find qualified hourly production people, and for that matter many technical, engineering service technicians, and even welders, and it is hurting our manufacturing base in the United States," he told a business audience Friday at the Spruce Meadows equestrian facility outside Calgary.

"The education system in the United States basically has failed them and we have to retrain every person we hire."

With that, he’s addressing one of the most heated debates in economics: how much of the current jobs crisis is structural. Oberhelmen’s statement comes on the heels of a Brookings report which argues that "education gaps" are causing higher unemployment in metropolitan areas that have lower educational levels:

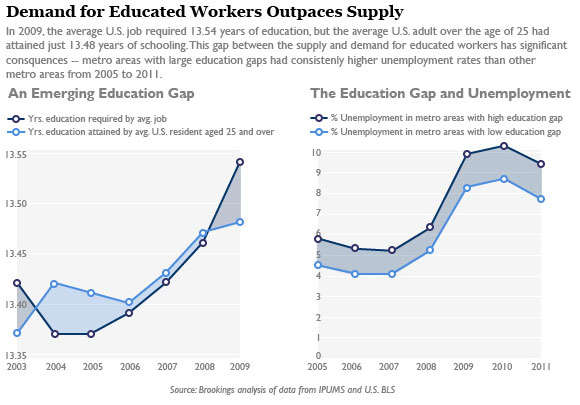

Metro areas with larger “education gaps”—shortages of educated workers relative to employer demand—had consistently higher unemployment rates than other metro areas from 2005 to 2011. Metro areas with larger education gaps experienced unemployment rates an average of 1.4 percentage points above metro areas with smaller such gaps. The difference widened to 1.7 percentage points by May of 2011, suggesting that better educated metro areas had a slightly larger advantage in the wake of the recession than they did before.

Or, in graph form:

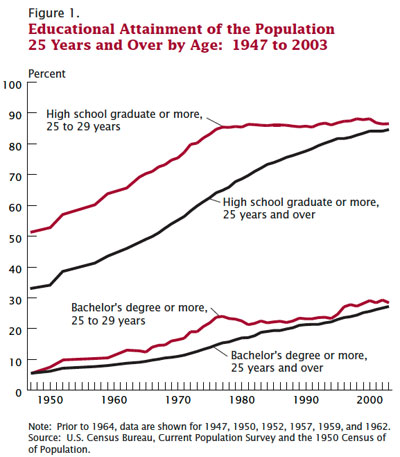

So have our schools failed us? Well, it depends on what you mean. "Educational attainment" has been on the rise since World War II (PDF), though the rate of growth has slowed:

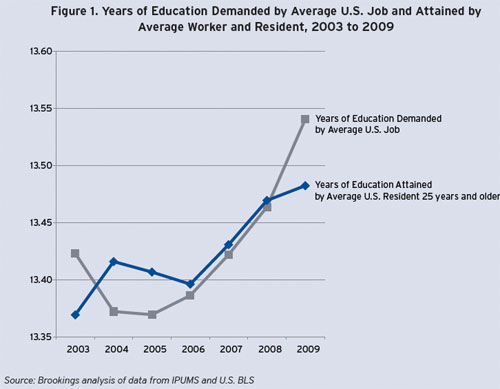

But after a brief dip caused by the construction boom, the years of education demanded by the average job has outpaced the average educational attainment:

Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, for what it’s worth, ranks 38th in Brookings’ list of metropolitan areas by "overall rank of education matching and predicted industry growth," just behind Charleston, South Carolina and Albuquerque. Madison, Wisconsin is second overall, and first in the "education gap" ranking, i.e. "the extent to which demand for educated workers outstrips the supply of those workers in a given regional labor market." The metropolitan statistical area we call home does a little better on that front, coming in 29th.

But the report warns:

Overall, the education gap explains roughly half of the variation in long-term metropolitan unemployment rates (averaged over five years from 2005 to 2010). But it only explains 28 percent of the increase from 2006 to 2011, and only 20 percent of the increase during the worst of the recession (2007 to 2009).

And not everyone agrees that high unemployment is attributable to structural mismatch. Brad DeLong shows that changes in unemployment between highly educated and not tracks over time, at least in terms of degree, and concludes that "unemployment always rises more for less educated workers in recessions and falls by more in booms":

More educated workers have bigger and better job-search networks, and the same things that made them more educated also make them make better use of their networks. When the labor market goes south, the consequences are much worse for those for whom the system does not work terribly well in normal times. But that doesn’t mean that any significant component of unemployment is "structural."

Last year, the Wall Street Journal had an intriguing blog post about a working paper co-authored by Stephen Davis of the University of Chicago’s Booth School, which presents a number called "recruiting intensity": "Their finding: Employers haven’t been trying as hard as they usually do. Estimates provided by Mr. Davis suggest that over the three months ending July, recruiting intensity was about 12% below the average for the seven years leading up to the recession."

Mike Konczal points out why the working paper by Davis, Jason Faberman, and John Haltiwanger is important:

This [BLS figure] is a binary, thin description of a job vacancy. A firm is searching or it isn’t. What Davis, Faberman and Haltiwanger point out is that a firm’s search for a job is a thick description, one that it can do with varying amounts of intensity, that the JOLTS data isn’t capturing. If firms are posting jobs but not trying very hard to fill the spots because of weak demand it can take the model Kocherlakota is relying on and turn it inside out.

In short, firms can wait for the best possible applicants since they don’t need to hire right now.

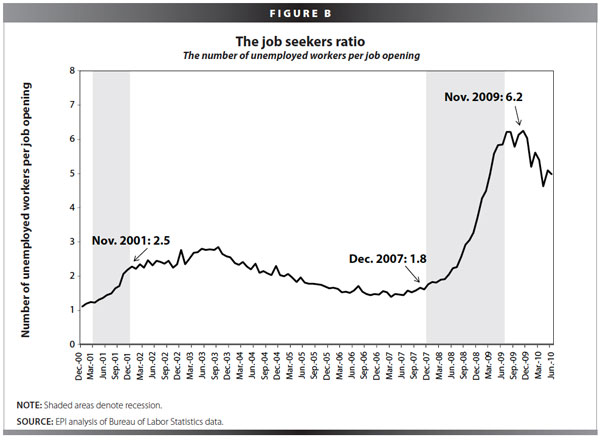

Finally, an Economic Policy Institute paper argues that the unemployment crisis can’t be chiefly structural, because even if firms filled all their openings (as of 2010), unemployment would still be high:

Simply put, the number of job openings has been far too few to accommodate those looking for work. As Figure B shows, the ratio exceeded six in the summer of 2009 but has dropped to the low five range more recently (once the Census jobs were filled). Even if the unemployed filled every job opening there would still remain many unemployed workers, an indication of too few job openings: in other words, even if every single job opening in the United States was filled, 80% of the unemployed would still be unemployed because there are no jobs for them. The ratio of unemployed to job openings in recent months has been nearly double that attained at the worst points of the early 2000s recession, a ratio of 2.8. This reflects, at least in part, that total job openings in the last half of 2009 were 25% below those in mid-2003, when the job seekers ratio was peaking in the last recession.

Photograph: roy.luck (CC by 2.0)