The National League of Cities just released a research brief, "City Fiscal Conditions 2011" (co-authored by UIC's Michael Pagano) that's good reading in the wake of the news—in particular the city inspector general's new suggestions for repairing the city's balance sheet and this month's Chicago cover story on Rahm Emanuel's very early tenure.

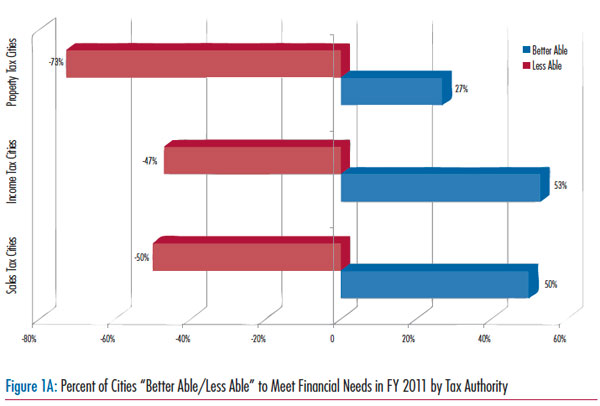

There's lots of very interesting data. This, given the ongoing property tax/TIF dilemma, jumped out at me:

What this chart says is that city finance officers surveyed by the NLC whose cities are most dependent on property taxes are finding it harder to get by. The City of Chicago is dependent on sales taxes and property taxes, and its reliance on the latter is regularly critiqued.

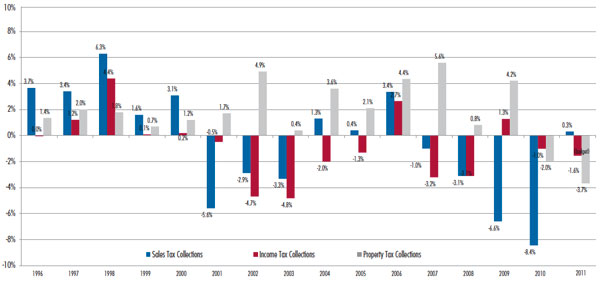

Figuring out what to tax is obviously tricky. Taxing a thing puts burdens on acquiring or doing things, so do you burden owning, working, or transacting? On the other side, you have to consider the consistency of revenue streams, which has long been the benefit of property taxes. Of all the things people do that create tax revenues, property taxes are appealing because that market moves more slowly and, historically, has moved consistently. Until it didn't:

The effects of the well-publicized downturn in the real estate market in recent years are increasingly evident in city property tax revenues in 2011. Property tax revenues in 2010 dropped by -2 percent compared with 2009 levels, in constant dollars, the first year-to-year decline in city property tax revenues in 15 years. Property tax collections for 2011 point to worsening effects from the downturn in real estate values, projected to decline by -3.7 percent. The full weight of the decline in housing values is now evident in city budgets, and property tax revenues will likely decline further in 2012 and 2013 as city property tax assessments and collections catch up with the market.

And the authors provide us with a handy table:

It's a bit hard to read shrunk down: blue is sales taxes, red is income taxes, and gray is property taxes, and it's measured just in year-to-year change in constant dollars. And it makes it easier to see the current problem for property-tax-based cities. Until 2010, property taxes could be relied upon to grow year over year. Sales and income, not so much, but their inconsistency is consistent. Relying heavily on property taxes is reminds me of some good advice I was given when I was thinking of getting a single-speed (or even an internally geared three-speed; no, not a fixie, thanks for asking) bike: yes, it's easier to maintain and less finicky, but in a serious headwind it's nice to have more options. If you don't have many gears, it's harder to build momentum into the wind.

So what are our civic peers doing about it? It's not hard to guess:

[T]he most common action taken to boost city revenues has been to increase the levels of fees for services. Two in five (41%) city finance officers reported that their city has taken this step. One in four cities also increased the number of fees that are applied to city services (23%). Twenty percent of cities increased the local property tax in 2011.

[snip]

When asked about the most common responses to prospective shortfalls this fiscal year, by a wide margin the most common responses were instituting personnel-related cuts (72%) and delaying or cancelling capital infrastructure projects (60%). Two in five (42%) reported that their city is making cuts in services other than public safety and human-social services….

What are they not doing? Modifying pension benefits (20%), public safety cuts (19%), and human services cuts (14%).

Think of the report as a handicapping sheet for how Mayor Emanuel and the City Council will address the budget crisis—it's not a guarantee, but it at least suggests where to place your bets. Many other cities face similar structural problems as Chicago; for all people like to talk about throwing the bums out, American cities share the same DNA, and are vulnerable to the same illnesses.