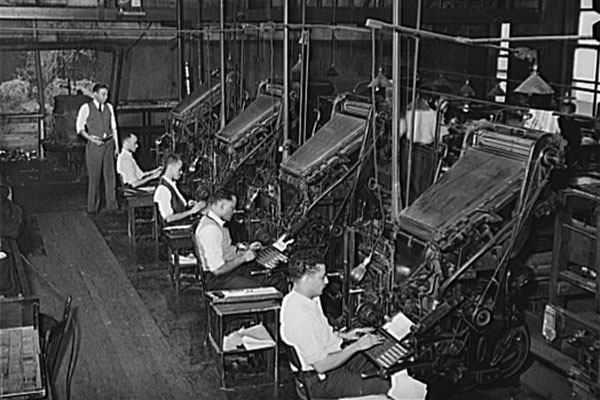

Linotype operators of the Chicago Defender, Negro newspaper. Chicago, Illinois.

In college I worked on literally the next-to-last run of the journalism ladder: I was a clerk—or something, I can’t remember the job title, and it was the sort of job where any title at all would have felt like résumé inflation—at the Center for Research Libraries, an island of misfit publications on the University of Chicago campus.

When a publication was deemed sufficiently useless to take up room in a university library, it was sent to me. Russian astrophysics journals, covers adorned with beautifully psychedelicized scientific charts; cheaply printed Cuban sugar-production journals charting the country’s struggles in mimeographed statistics; Indonesian gourmet food magazines; Eastern European automated-packaging trade mags; Indian equivalents of People and Marie Claire.

Every day, enough people doing research across the whole world would occasion me to work, reversing the process. I’d retrieve four or five publications, mark the articles, and wheel the little pile to the next department. This is what a search engine must feel like, I thought. Or a few lines of its code, anyway.

Then I’d be tasked with makework, straightening and retying the bundles, devoting attention to the stacks mostly for its own sake. To stretch the hours I’d read through the world’s marginalia, or at least look at the pictures.

In retrospect it was a good job for someone who wanted to write or edit or do layout. When you learn to write, they tell you to "kill your children." What goes unsaid is that sometimes they just die of their own accord.

But I took a small pleasure in being the penultimate step in the life cycle of a publication: the satisfaction of releasing my keep back into the world, and the mystery of what it would become in someone else’s head. Nothing, perhaps. But how we think about work is half the job.

In that spirit, here are five excellent reads about people doing work in these parts. Happy Labor Day.

Ben Hecht, from "The Tattooer," in 1,001 Afternoons in Chicago:

"Oh, we still do business," says Dutch. "Human nature is slow to decline and there are people who still realize that if you got a handsome watch what do you want to do to it? Engrave it, ain’t it? And if you got a handsome skin, what then? Tattoo, naturally. And we tattoo in seven colors now where it used to be three, and use electricity. Do you think it’s crazy? Well, you should see who I used to tattoo in the old days. Read the article on the wall. As for being crazy, what do you say about the man who spends his last 50 cents to get into a baseball game, and gets excited and throws his only hat in the air and loses it, and the man who sits all day and all night with a fishpole on the pier and don’t catch any fish? Yes, like I tell the judge who picked us up one day in Iowa, you know how they do sometimes when you follow the carnival. And he asks me why I shouldn’t go to jail, and if tattooing ain’t crazy, and I says give me three minutes and I prove my case. And I begin with the Romans, and how they was the brightest people we knew, and how they went in for tattooing, and how Columbus was tattooed, and all the sailors that was bright enough to discover America was tattooed, also. Then I say, what if Charlie Ross was tattooed? Would he be lost to-day? And what if he had under his name the word Philadelphia? And in addition to that the date where he was born and his address and so on. Would he be lost then? ‘You see,’ I says, ‘a man can’t be tattooed enough for his own good,’ and the judge says I win my case."

Lee Sandlin, from "The American Scheme":

The inexhaustible wealth of America was turned over to developers, franchisers, packagers, and deal makers. There were hotshots everywhere — my father kept meeting them on his rounds, importantly pacing around tacky airfield waiting rooms, mouthing off in motel bars: Regular Guys on the make. They were living off loopholes and longshots, seeing bright opportunities where everybody else saw implacably dull regulations: and they were getting rich at it.

The Federal Housing Authority, which financed the development of the suburbs, was causing the houses to go up in unimaginable numbers: but still the demand wasn’t sated. The unused land was left wide open to the operators. Developers who wouldn’t or couldn’t deal with the FHA were building whole Kleenex-box towns out of nothing, merely by cutting enough corners to be competitive without government money. Then, too, the basic FHA look wasn’t for everybody — they were only willing to approve bland, middle-of-the-road designs, free of oddity or originality; so some developers were going upscale, and building "communities" of lavishly grotesque boxes sprawled over acres of ex- pasturage, in mutant styles like Tudorette, Scandinavian Sauna, Plast-o-Spain. But whether you went high or low, there was a fortune to be made — if only you could put the deal together.

This kind of thinking mesmerized my father. He could spend hours talking through baroque deals with his instant friends — Gaudi towers of kited financing, hypothetical cities he’d worked out like crossword puzzles as he surveyed the land from the air. He knew nothing about the construction business, but he could retain and understand the arcana of taxes and mortgages the way some people know sports stats (and he knew those, too). Still, I don’t think he ever took any of this shared daydreaming seriously; it evaporated as soon as the bar closed or the fog lifted; until he finally met a guy who called him back the next day.

Richard Lalich, from "The Wet Dreams of Mr. Sybaris":

"Sure, it’s cheesy," a woman whose children are in college told me. "But it’s a great place to go do it." When you think about it, it’s as pithy a slogan as any Knudson might conjure up.

Knudson, 47, a former tool-and-die worker, race-car driver, and karate instructor, delivers his sales pitch with an evangelist’s verve. If he garbs himself in Sansabelt slacks and polyester ties, it may be because he has invested every dollar of his own (and a lot of cash from other people) in a business that is no less than a mission, he would have you believe, to save American matrimony. No weapon is left unfired. In an office at the Northbrook resort, he brandishes a copy of Reader’s Digest and reads from it at length–an article by Dr. Joyce Brothers on the romantic malaise of married people. Then he springs from his chair and stalks the room, slapping walls, as he explains the origins of Sybaris, back in the era of discos and The Love Boat….

Dmitry Samarov, from "Mood Director":

Last night a radio call brought me back to the cinderblock condo in Humboldt. The guy recognized me right away, “You got a card? It’s a real bitch getting a cab around here.” I told him I didn’t. He gave me his though. It had his name and Mood Director underneath.

“Remember that mascot costume? It’s a bear suit and in the place I work at there are go-go dancers up behind the bar and they’re getting sprayed with water, like they’re taking a shower. The guys eat that shit up…I sneak up behind the ladies, in full costume, and pretend to be doing ‘em,—‘Uh, uh, uh,’—you know, it’s my job to make sure everyone’s having a good time. Thinking next I’m gonna be a gorilla and I’ll get one of the other guys to dress like a giant banana and I’ll chase him all over the club. Awesome, right? We have pillow fights, all sorts of crazy shit…I do one of these stunts and you should see all the cameras come out, flashes all over the place, click, click, click!”

Steve Rhodes, from "Devils’ Advocate":

By various accounts, Genson’s best bit of courtoom theatre features a recurring idiosyncrasy-his limp gets worse during a trial, the better to gain the sympathy of a jury. Genson has encouraged that analysis, but Turow says the truth runs deeper. "When he gets under stress, his symptoms do get much worse," says Turow. "So when he starts trying cases, he is limping more because he’s in more pain. But he’s such a wily bullshit artist that, rather than let people know that he was actually in pain, Eddie for many years had the assistants in the U.S. Attorney’s Office believing that he was just limping more to excite the jury’s sympathies. And that’s what I mean by burnishing his own legend. By point of fact, the guy was suffering, but he didn’t want his opponents to know that it was physically hard on him, because then maybe they would extend a three-week trial to four weeks."

Photograph: Russell Lee / FSA-OWI