In March 1920, on his third and final visit to Chicago, William Butler Yeats explained his dramatic ideal to a crowd at the Casino Club. “I am trying,” he said, “to create a form of poetical drama played by one company, all of whom could ride in one taxicab and carry their stage property on the roof.”

Now, with the help of Bernie Sahlins, gyre incarnate, it appears that the Irish poet, playwright, politician, and mystic will realize his dream in a limited Chicago engagement. On Sunday and Monday at 7 p.m., at its new home at 61 West Superior Street, the Poetry Foundation will stage Meet Mr. Yeats, a new play—though Sahlins, its director and author, would not call it that. “It’s a reading,” he insists, and then backtracks. “I don’t know how I would describe it. I’d rather use a bunch of words,” he says, and grandly pours out the promised volume, with only occasional references to his 42-page “script.”

Sahlins has conjured a recreation of Yeats’s life based on his three memoirs and, especially, his poems, about 30 of them. The Second City patriarch was pushed in that direction by John Barr, the foundation’s president, who, Sahlins says, “long had the idea of personifying the poets. I chose Yeats because his poetry is great—and he had a very eventful life.”

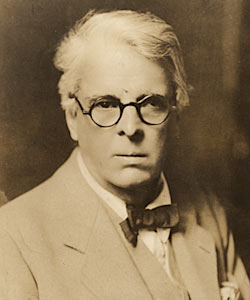

To work his magic, Sahlins has assembled a taxi-size troupe of black-clad incantatory familiars. Bruce Jarchow channels Yeats, albeit with certain shadings. “I didn’t try to make him a facsimile,” Sahlins says. “[Jarchow] doesn’t have an Irish accent that would pass muster. Most actors don’t. He’s an American doing Yeats.”

As Yeats (Jarchow) unfolds his autobiography, three other actors—Tim Kazurinsky, Suzanne Petri, and John Mohrlein—interrupt his reminiscence with recitations of pertinent poems, starting with “A Coat” (“I made my song a coat / Covered with embroideries / Out of old mythologies”). “You don’t have to introduce that poem,” says Sahlins, “ and it serves to characterize the spiritual side of Yeats’s life: his attachment to the Irish occult, to fairies and spirits.” Other featured poems include “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” “The Second Coming,” “The Wild Swans at Coole,” and “The Fisherman,” a Sahlins favorite. “I’m particularly in love with its ending,” he says, before reciting Yeats’s vow to a sun-freckled Irish angler: “‘Before I am old / I shall have written him one / Poem maybe as cold / And passionate as the dawn.’”

Sahlins made his selections by choosing poems that illuminated the production’s narrative. “In order to get it to a viable length, I had to let go some [biographical] things that didn’t lead directly to poems,” he explains. Alternatively, he jettisoned some celebrated poems that didn’t fit the arc of his storyline. He did make an exception for “Sailing to Byzantium.” “I dragged that in by the roots because I like it. I introduce it as the story of an old man taking a journey to a mystical world of art to be immortalized as a statue of gold.”

The women central to Yeats’s life are referenced: the beautiful rebel Maude Gonne; Lady Gregory, with whom he founded Dublin’s Abbey Theatre; and his wife Georgie Hyde-Lees, whom Yeats met when he was 45 and she was 17. Not surprisingly, the performance wraps up with the poet’s self-crafted eulogy, “Under Ben Bulben,” the actors intoning in chorus its concluding epigraph, the same words carved on Yeats’s tombstone:

Cast a cold eye

On life, on death,

Horseman, pass by!

The performances are free, and there is room for only about 100 guests each night, but reserve tickets are available online.

• Other than Dublin, there might be no better setting than Chicago for Meet Mr. Yeats. The poet was fond of the city, visiting it first during his 1912 lecture tour of the United States. He made a second tour of the country two years later, and it left him physically, mentally, and spiritually exhausted. His return visit here, in the late winter of 1914, was the highlight of the trip. “He was happiest in Chicago,” writes R. F. Foster, Yeats’s best and most recent biographer. “. . . [T]he intelligence and energy of the Chicago literary world pleased him, and only there did he seem to rediscover his pleasure in America.”

Part of that delight stemmed from his hostess, Poetry’s founder Harriet Monroe, whose small apartment in the Virginia Hotel (at Rush and Oak streets) Yeats shared for a week. Between his public appearances, he and Monroe shopped for luggage on Michigan Avenue, attended a performance of his verse play The King’s Threshold at the Fine Arts Theatre, and dodged reporters while visiting an Edgewater spiritualist.

Yeats’s visit also occasioned the most eventful literary gathering in Chicago’s history. On March 1, before a large dinner crowd at the rooftop Cliff Dwellers club on South Michigan Avenue, he implored the city’s poets to rid their verse of Victorian diction and chase after “a style like speech, as simple as the simplest prose, like a cry of the heart.”

As an example of what he was seeking, Yeats singled out the 34-year-old Springfield poet Nicholas Vachel Lindsay, who had tramped across the country preaching his “Gospel of Beauty” and trading his poems for lodging and food. Monroe made sure Yeats read Lindsay’s “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven” in the latest edition of Poetry. Enchanted, Yeats called the hobo poet to the fore, and Lindsay responded with a widow-rattling performance of his epic, ragtime “The Congo.” Chicago’s grande dames rushed to embrace him, inaugurating a vogue for Lindsay’s poetry that would tragically fade out after World War I.

As for Monroe, she would look back at that evening in her autobiography and call it “one of my great days, those days which come to most of us as atonement for long periods of drab disappointment or dark despair. I drew a long breath of renewed power, and felt that my little magazine was fulfilling some of our seemingly extravagant hopes.”

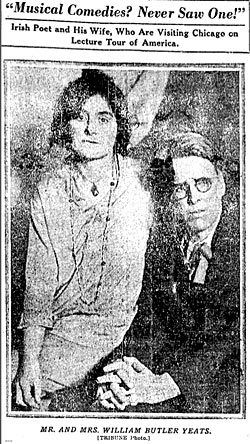

• In 1920, during the early months of Prohibition, Yeats came back to Chicago, intent, it seems, on showing the country how to have a good time. Awakened after midnight at the Auditorium Hotel by a call from the Tribune—“I’m in bed,” he grumbled—Yeats offered up his thoughts on the city. “I like Chicago,” he said, “but Prohibition’s hell, isn’t it.”

That lament caught the city’s fancy. Monroe was the first to respond, showing up at Yeats’s hotel room with an overloaded purse. “I read in the Tribune this morning of your unpreparedness,” she said, and presented him with a half pint “flagon” of what she called “surcease for your sorrow.” (The Trib headlined the story of Monroe’s visit “Magic Handbag Yields Pierian Nectar to Yeats.”)

Not to be outdone, the city’s reporters, who had gathered for late night carousal in a private dining room at the Auditorium, took it upon themselves to again arouse the poet from his bed. Carried into the reporters’ room, he “appeared [recalled one journalist 35 years later] to be startled and not so sure what had brought him to the party.” He perked up, however, at the offer of a glass of whiskey. He downed one glass, accepted a second and a third, and might have remained for the night had not “a woman [his wife] sailed into the room.” Yeats stood up with slow dignity, and as his wife steered him toward the door, he thanked the assembled gentlemen with a few lines of poetry, presumably proffered in tipsy jest: “And I shall arise and go now, and go to Innisfree . . . .” No wonder he loved this city.

• In 1968, Yeats “came back” for a posthumous curtain call. That summer in Chicago, the folk singer Phil Ochs performed for the young protestors drawn to the Democratic Convention. Disillusioned by the brutal police violence he encountered there, Ochs responded with his album Rehearsals for Retirement, which included the song “William Butler Yeats Visits Lincoln Park and Escapes Unscathed.” Except for the contemporary references, the lyrics—which invoked a blood-red moon, a fair young maiden, and trembling towers—might have sprung directly from Yeats’s Celtic Twilight. But the album failed to lift Ochs’s depression. Like Lindsay before him, the folk singer succumbed to a mad paranoia and chose suicide as a way out. Only 34 years old, Ochs hung himself in April 1976. Horseman, pass by!