A few weeks ago, Carol Felsenthal asked whether the U.S. Postal Services’ planned closing of 3,700 post offices and converting them to retail-location-based "village post offices"—you can see the entire list here—would impact Chicago’s poor neighborhoods the hardest, and how. But post-office closings would hit small towns hard, as you’d know if you grew up in one; Millington, pop. 665, is fighting for its own:

It seems pretty ridiculous to many in this town of 665 on the Fox River in southwestern Kendall County, where the post office and City Hall are the only two official buildings in town. Those are the places where city meetings and notices are posted, where people go to find out what’s going on.

For me the Postal Service has never been the same since they replaced the old Cloverdale, VA post-office shack with a generic 1980s brick-and-boredom shotgun building. The old one is what I imagined the one in "Why I Live at the P.O." looked like.

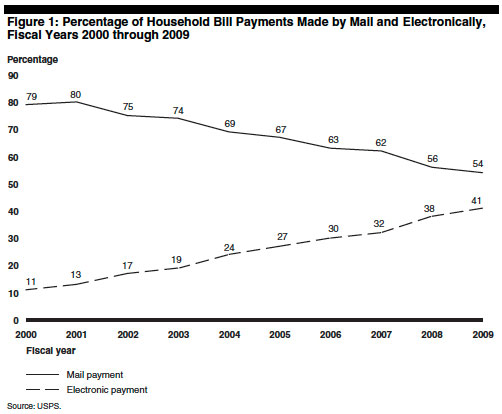

There are a couple reasons the USPS, as it is, is doomed. Here’s one:

And it’s not just bill payment that is moving online; now that I get almost all my bills online, I had trouble digging up the right paperwork to get my driver’s license renewed last week.

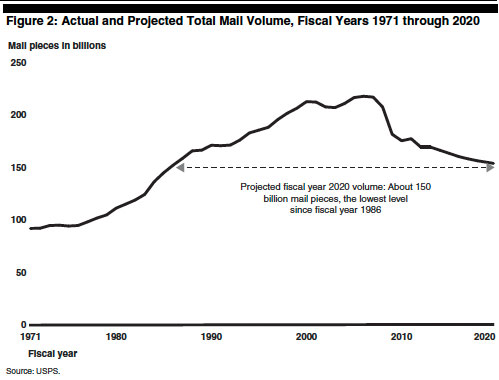

Here’s another:

That graph surprised me a bit, but then I remembered all the come-ons I got during the housing (and credit) boom of the last decade. As taking care of basic necessities like bill-payment and letter-writing has moved online, the USPS as advertising medium helped keep the organization afloat. Then all economic hell broke loose:

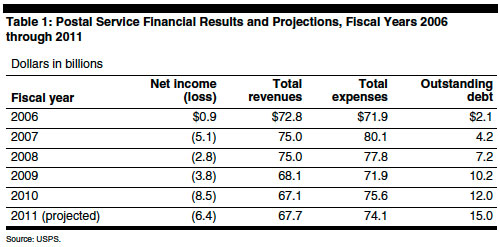

Note the seven-billion-dollar drop in revenues between 2008 and 2009, and the subsequent doubling of the service’s outstanding debt between 2008 and this year’s projection. According to the Postal Regulatory Commission (PDF), ten of the USPS’s "market-dominant products," like periodicals—another victim of the online revolution—and standard mail flats lost $1.7 billion.

Another reason the PRC cites is 2006 legislation requiring the USPS to prepay 75 years’ worth of employee benefits over 10 years—which sounds great in an era of underfunded pension plans, but has required USPS to pay about $5.5 billion per year to do so. The result, according to an Economic Policy Institute study, is an excessive burden:

The Postal Service was debt-free at the end of its 2005 fiscal year, but ended the 2009 fiscal year—three years after the pre-funding requirement began—with $10.2 billion in debt. It could borrow another $3 billion in 2010 and could hit its $15 billion statutory debt limit in 2011. Unfortunately, the Postal Service is not using this increased debt to modernize its facilities or lay the groundwork for new services when the economy recovers (USPS 2007).

Speaking of being locked into structural problems: the biggest reason, broadly speaking, for the service’s decline is its long transition from government program to heavily-regulated "independent establishment of the executive branch of the Government of the United States," which grants it increasingly useless monopoly powers (delivering to post-office boxes, for example) while tying its hands in order to maintain it as a public good with regards to business operations… and making it pay for itself. The result, naturally, is subpar offerings (eg poor tracking) at reasonable prices.

We’re not quite at the reckoning for the USPS, but we’re close. The first step, the Washington Post‘s Ed O’Keefe reports, is giving it an extra 90 days to meet its pension-funding requirements. After that there’s the bleak future.

One option, as outlined in an outstanding Bloomberg Business Week article, is to go European. Which is more free-market than the U.S. postal system, with its awkward IEEBGUS structure:

Three decades ago, most postal services around the developed world were government-run monopolies like the USPS. In the late ’80s, the European Union set out to create a single postal market. It prodded members to give up their monopolies and compete with one another. The effort roused an industry often thought to be sleepy and backward-looking.

Many countries closed as many of their brick-and-mortar post offices as possible, moving these services into gas stations and convenience stores, which then take them over—just as the USPS is trying to do now, only far more aggressively. Today, Sweden’s Posten runs only 12 percent of its post offices. The rest are in the hands of third parties. Deutsche Post is now a private company and runs just 2 percent of the post offices in Germany. In contrast, the USPS operates all of its post offices.

The University of Chicago’s Gary Becker suggests letting it operate like an independent business, since it has to pay for itself like an independent business:

Defenders of the postal service correctly point out that part of its troubles is due to regulations that significantly raise its costs of operation. These include the requirements to deliver first class and some other mail 6 days a week at uniform prices to about 150 million residences, mailboxes, and businesses, including very remote locations that are costly to serve. Most mail prices can only be raised according to a formula fixed in 2006, and the USPS is restricted from entering new businesses.

Remote locations like the appropriately named Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. The USPS was going to cancel its $46,000-per-year air mail route, the last in the continental United States to that neigborhood’s 20 residents, clearly a futile business decision… until the Idaho congressional delegation got them to reconsider.

Photograph: -Tripp- (CC by 2.0)

Comments are closed.