.jpg)

During her speech last night, which may turn out to be the most well-remembered this cycle that wasn't improvised with an empty chair, Michelle Obama painted a moving portrait of her father, Fraser Robinson III. The grandson of a slave, Robinson attended college for a year, but dropped out because of debt and went to work as a pump operator for the City of Chicago. But his job, the sort of stable, reasonably well-paying laborer's job that gave so many men of his era to a middle class life, allowed him to help both his siblings and his children through school, who went through a process familiar to anyone who couldn't pay the full ride:

And when my brother and I finally made it to college, nearly all of our tuition came from student loans and grants.

But my dad still had to pay a tiny portion of that tuition himself.

And every semester, he was determined to pay that bill right on time, even taking out loans when he fell short.

He was so proud to be sending his kids to college…and he made sure we never missed a registration deadline because his check was late.

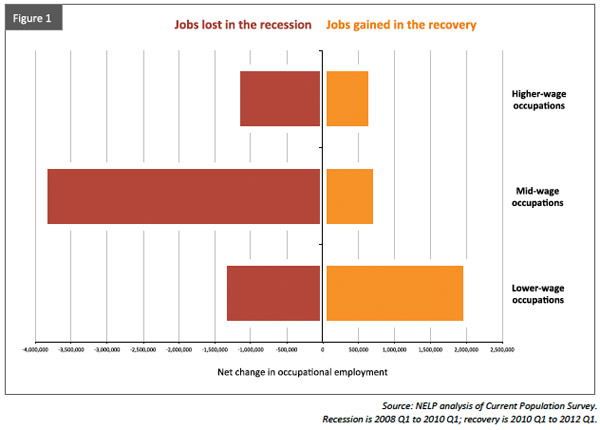

Michelle Robinson went on to Princeton and Harvard, landing at the prestigious firm Sidley Austin. It's a familiar but admirable story that reminds me of my own family; watching it, I wondered: how long will jobs like that continue to exist? The current recession has wiped out many of them, and the recovery has added, in their place, low-wage jobs (PDF):

For many, in Michelle Robinson's family and my own, mid-wage occupations available to those who hadn't finished college were leverage out of poverty, that gave their children the chance to attend college and expand their goals: mobility, in a word. And a working paper by the Chicago Fed's Bhashkar Mazumder suggests that slope has lost its traction for men like Fraser Robinson III (PDF, emphasis his):

the results show that blacks are both substantially less upwardly mobile and substantially more downwardly mobile than whites. Should these patterns of mobility persist, the implications for racial differences in the steady state distribution of income would be alarming. Instead of “regressing to the mean” as the standard IGE [intergenerational elasticity] estimates would imply, these results would instead imply that blacks would largely remain a permanent underclass.

But the differences are less stark with educational attainment:

With respect to the racial gap in upward mobility, controlling for education provides something of a mixed picture. The racial gap in upward mobility among those with less than a high school education is actually higher than the unconditional estimate. On the other hand the racial gap narrows sharply with additional years of post secondary education. Indeed among those with 16 years of schooling the racial gap in upward mobility gap is essentially closed.

But only after a certain and very important limit:

Nevertheless, the racial gap is still quite large among those with some post-secondary education but who have not completed college. For example, the black white gap among those with 14 years of schooling is still sizable at 16 percent. Given that only 17 percent of blacks in the NLSY attained more than 14 years of schooling, this suggests that marginal improvements in educational attainment may not do a great deal to improve the overall upward mobility prospects of blacks.

Finishing college negates the mobility gap. And it's passed down to the next generation: "As with own education, the black-white gap is essentially closed if one’s father completed 16 years of schooling."

Programs that get kids to college who otherwise wouldn't attend are critical, as is the opportunity to pay for it:

Another key variable concerning parental status that could plausibly influence patterns of upward mobility is wealth. Becker and Tomes (1979, 1986) have suggested that rates of intergenerational mobility could be lower for families who face borrowing constraints and who therefore cannot optimally invest in their children’s human capital…. For whites upward mobility rises with wealth in the bottom half of the wealth distribution but is fairly flat in the top half of the distribution. For blacks, there is a more striking upward slope at the bottom end of the wealth distribution and a similar leveling off in the middle of the distribution.

But as long as that mediating step between poverty and stability continues to decay, the ladder, as Mazumder's research suggests, will be that much harder to climb.

Photograph: Chicago Tribune